Parity of esteem for Mental Health is the principle that mental health must be given equal priority to physical health. NHS England defines this as CCGs spending the same percentage of their allocation on mental health as they have done in previous years. With Jeremey Hunt claiming that 85% of the country is meeting parity of esteem1and it being relabelled the ‘mental health investment standard’, one would be mistaken for thinking that parity of esteem was just about the money.

However, parity of esteem is much greater than this, as patients who have suffered from poor access, or who have been detained under Mental Health Act or children, young people and adults who have been sent out of area for treatment, can attest to. These differences in quality of care can be highlighted in an emergency. If a person is suffering for an acute psychotic episode or is contemplating suicide, often it is not an ambulance that will attend the scene but the police, with crisis teams frequently unavailable. However, for those with a life threatening physical health need, an ambulance is expected to be there within eight minutes. The reasons for these differences in quality of care are far greater than just the money.

Firstly, one difference is that while the data on mental health patients exists and is collected nationally, mental health trusts don’t use it like acute trusts to gain reimbursement from CCGs.

Acute providers used their patient level data to charge CCGs for the number of patients and the type of treatment on a case-by-case basis, using the national tariff. This means as acute activity increases, acute hospitals see an increase in income. Mental health trusts have not benefited from such a mechanism. Instead, mental health may see an increase in activity, but this does not automatically lead to an increase in income. This can adversely impact on the quality of care provided as they are supply constrained. A side effect of this payment mechanism is that, when trying to invest in new mental health services, to improve outcomes or reduce other types of activity, it makes it virtually impossible for mental health trusts to show the positive impact that investment or new treatments will have on costs to CCGs. To have parity between mental and physical health, a similar mechanism of recognising changing demand and linking this to allocating resources should be provided, based on population need. Parity of esteem requires commissioner support to invest in the mental health services that are used by their population and recognition that this can reduce costs elsewhere in the system, for example reducing the number of people being admitted to acute hospitals when the real diagnosis is one of Mental Health.

Secondly, the amount of research which is carried out means that progress in understanding mental illness, its causes, treatment and prevention is far behind that of physical health needs.

Comparing the amount spent on research by charities shows that in 2016/17, Cancer Research UK has a spend of £665m2, MQ; the mental health equivalent, has a spend of £4.1m2. Government spend is also vastly different. In 2015/16, the medical research council (MRC) spent just over £25m3on research directly addressing mental health questions and in 2014 it spent £76m on cacer3alone, alongside other physical health conditions. Could this be why 90% of patients get an evidence-based intervention in cancer but only 10-15% get an evidence-based intervention at the point of treatment for mental health?

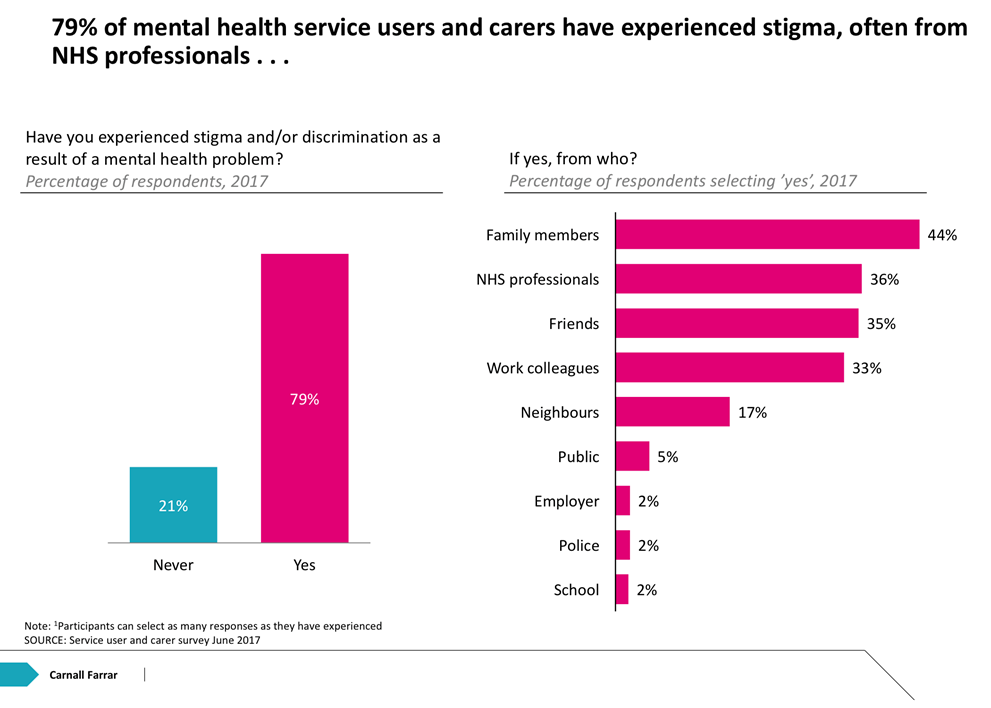

Thirdly, people who suffer from mental ill health experience stigma.

This is from people in every walk of life, inside and outside the NHS. Within the NHS this can mean people losing confidence in seeking help and no longer attending appointments. It means vital support networks that people might rely on may not exist as they find it difficult to tell friends and family that they are seeking help or taking drugs, often feeling like it is an admission of failure4. In work, people are wary of admitting their sick day was due to mental health5. While these attitudes are slowly changing, until people have confidence in stating their mental health needs as they would their physical health needs, parity will never be achieved. Mental Health Awareness week seeks to highlight and confront this, but this needs to be something we all do all the time and recognise that ‘it is okay to NOT be okay’.

In summary, mental health accounts for 23% of activity but only 12% of NHS spend6 and historically, has been under invested in.

If, we believe that previous levels of mental health spend is the right amount of investment in mental health, then the mental health investment standard means that mental health will not lose more ground to physical health as NHS budgets become increasingly stretched. However, unless we address the underlying historic differences in how our mental and physical health needs are treated inside and outside the NHS, parity will not be achieved.

Sources:

1HSJ Summit Nov 2017, 2MRC, 3charity commission, 4BBC Radio 1 Life Hack’s 19/11/17, 5BBC news 13/7/2017, 6Mental health five year forward view