With the advent of several first generation GLP-1 agonist ‘disease-modifying’ therapies in obesity, CF, a leading healthcare consulting and data company, conducted a thorough review of the ecosystem that these medicines are being launched into. The epidemiology and health economics of obesity are well-known and rehearsed in multiple articles [1,2,3], however, the clinical pathway is rarely reviewed and characterised in its entirety. The advent of these new medicines has catalysed a complete rethink of the way that the NHS views and commissions obesity pathways. We investigated the evidence and talked to a spectrum of over 25 leaders and experts, including people living with obesity, leading academics, senior clinicians across the pathway, commissioners, policy-makers and pharmaceutical leaders. This thought leadership summarises our findings at the highest level and aims to propose practical next steps in the UK.

Obesity has become an epidemic that is not equally distributed across the population

Since 1975, obesity rates have tripled in England and are now the highest in Europe [4]. 63% of adults in England are overweight or obese [5], and 1 in 3 children leave primary school overweight or obese. And the burden is not shared equally. Whereas excess weight used to be the preserve of the rich, in western countries it is increasingly the preserve of the most deprived populations. Children in these groups more than twice as likely to be obese than their peers in least deprived areas.

Obesity is associated with reduced life expectancy and is a risk factor for numerous health conditions, including type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and stroke, respiratory, musculoskeletal and liver diseases, at least 12 types of cancer and poor mental health [6]. There were about 900,000 recorded obesity-related NHS hospital admissions in 2018/19 and the rising prevalence of obesity suggests an overwhelming burden of related diseases in the coming decades. We will look at the financial impact of this epidemic later but, suffice to say, the cost to society is immense.

The current approach to obesity management in the UK is flawed

Obesity management is complex. The UK government’s 2007 Foresight Report [7] into obesity eloquently describes a complex network of hundreds of contributing factors to developing obesity. In 2019, Public Health England published a six-phase ‘how to’ guide to support local efforts to promote a healthy weight [8] from engaging stakeholders to conducting system mapping and action planning workshops. In 2020, a new obesity strategy [9] was released urging the country to lose weight to beat COVID-19 including getting active and eating better, banning TV and online advertising for food high in fat, sugar and salt before 9pm, ending deals on unhealthy foods high in salt, sugar and fat, displaying calories on food labels to help people make healthier choices. A representative of a prominent public health body recently told us ‘[public health leaders] should stop beating ourselves up over obesity. This is going to be almost impossible to solve at a public health level.’

The obesity strategy also made the somewhat vague commitment to expand access to NHS weight management services. However, critical to helping the NHS play its part is not just improving access to services but improving the overall pathway of weight management itself. It is worth re-evaluating what we are doing at all levels of the health ecosystem, not just in public health, and taking a hard look at what works and what doesn’t. Our recent work reveals that the healthcare ecosystem’s approach to tackling obesity suffers from three issues:

- Inadequate resources in terms of focus or budget

- Limited data, evidence base and knowledge of best practice

- Fragmented treatment pathway underpinned by outdated assumptions

1. Inadequate resources and focus

The UK government is publicly engaged with the problem. For example, it has pledged to halve childhood obesity and significantly reduce the gap in obesity between children from richest and poorest areas by 2030. However, in practice, tackling obesity is a back-burner issue with a limited plan. The NHS does not classify obesity as a medical long-term condition and typically frames the issue in terms of type-2 diabetes. Obesity has a relatively insignificant £100m NHS budget plus a recently announced ‘£20 million research boost’ [10]. This averages out as at a derisory £5 annual spend per overweight person. Consequently services are very limited with patchy coverage.

2. Limited data, evidence base and knowledge of best practice

Significant questions remain among clinicians around how to classify and treat obesity. These are hard to answer in the absence of good data both in terms of range of metrics and depth of sample. Studies have often been of limited use and might report, for example, statistically significant population-level outcomes that may not be clinically significant. For example: weight loss of 1 kg at 1 year may be statistically significant but makes no difference to someone who is battling to lose 30 kg for the long term. Because we have limited data on the chronic lifecycle of obesity the system tends to focus on the acute outcomes of the condition.

In the UK, obesity data at national level is only available as a subset of diabetes data and audits and is difficult to access and disaggregate. Efforts are ongoing to gather information as part of a national endocrinology database. However, this project is in the early stages. Increasingly there is a huge amount of data recorded in weight-loss apps or diet programs, but this data is not integrated or captured with health records. Phase III trials in novel obesity therapeutics may create the driver for deeper more clinically focused evidence gathering.

3. Treatment pathway underpinned by outdated assumptions

Because of this evidence gap, there is no empirical approach stratifying patients into treatment. However, taking a hypothesis driven approach where tackling obesity earlier in its course is clearly more efficacious than waiting until crisis point. In the NHS, patients are treated based on self-referral, urgency of complications or time on waiting list. For both patients and the system this is too little, too late. Even once in the system, the collection of services does not hang together as a pathway.

Because of its multifactorial nature, what is clear is that a multidisciplinary approach is required. The necessary toolset requires a range of interventions working in concert and with front-loaded support where possible, including:

- Information and education

- Diet, exercise and lifestyle

- Psychology and coaching

- Medical intervention and pharmacotherapy

- Bariatric surgery

- Management of complications

- Ongoing follow-up and support

Examples of this MDT model are rare but exist in small pockets for example at the GP-led Rotherham Institute for Obesity and the Fakenham Medical Practice in Norfolk. Both have yielded excellent results [11,12].

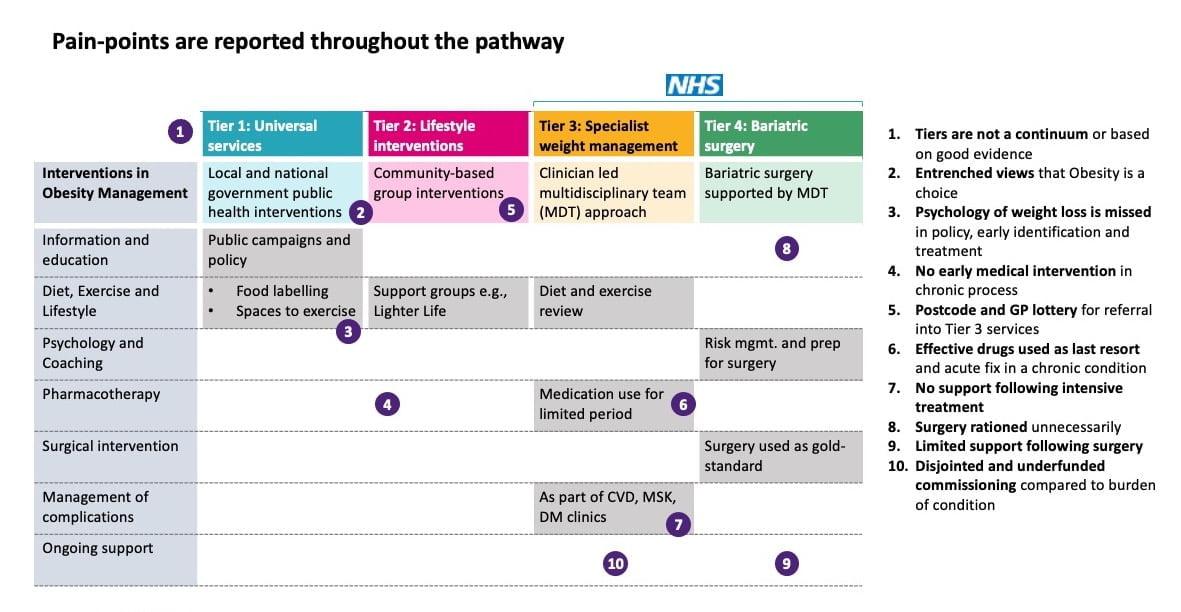

However, what we actually see as the NHS approach to weight management in England is quite different. This has 4 tiers although these are not connected, there is no clear link to the MDT approach and there is a postcode lottery of who has access to expensive Tier 3 and Tier 4 services, as seen in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Pain-points in the current NHS obesity management pathway.

There are significant opportunities for improvement

As outlined above, the current approach to obesity management is flawed and there is clear opportunity to improve. To do this, we must:

- Recognise and work towards the ‘size of the prize’ at stake

- Work to change the national mindset

- Recognise the inflection point brought by disease modifying therapies

- Create a coherent pathway that works for the patient and the system

- Use the potential of the NHS Integrated Care Systems to develop the new models of care

1. Recognise the size of the prize if we can address obesity

To put a price-tag on it, £58 billion a year is the estimated wider cost of obesity to the UK according to a 2022 study commissioned by Novo Nordisk [13]. A 2014 study by McKinsey estimated that obesity costs $2 trillion globally each year, one of the top three man-made global social burdens [14], after smoking and war (and double, at the time, the cost of climate change). They estimated that, in the NHS, £6.1 billion is estimated to be spent by the NHS on obesity-related illnesses each year. That report’s data is over 10 years old, and since then the problem has only become more entrenched.

Put more positively, a reduction in the prevalence and severity of obesity would improve health outcomes for millions of people and result in significant cost savings to the system. It would reduce pressure on doctors and nurses and free up resources to treat other sick and vulnerable patients. In society more generally, an uplift of £58b to UK GDP, equivalent to the estimated economic impact of 4 fully delivered HS2 rail projects [15] is worth investigating, and, who knows, might be better value.

2. Change national mindset around obesity

Many people living with obesity feel an immense psychological burden and stigma around their condition. One person living with obesity who we spoke to said ‘[it is] my defining characteristic in the eyes of other people. Everyone has a judgement about it. [It is] something that I cannot hide and one that, however hard I try, I [can] not reverse by myself.’ In 2018, 42% of people with obesity reported not feeling comfortable talking to their GP about their obesity, and only 26% reported being treated with dignity and respect by healthcare professionals [16].

Weight prejudices, stigma and discrimination are common in schools, universities, the workplace, the media – in fact almost everywhere – and can create a spiral of despair in people with obesity [17]. Public discourse can spill over into sounding like it is blaming people for being overweight and causing pressures on the system of their own choice. Health care professionals (HCPs) may contribute to this by ascribing stereotypical characteristics to people living with obesity and not providing the required advice, support and care. Many report that HCPs fail to see past the obesity to other presenting concerns and treat them with limited patience when they seek help. Clearly, good communication is critical in healthcare [18,19,20,21].

Moving forwards and making progress with obesity must start with shifting the national mindset. This should begin with NHSE recognising obesity as a serious and essentially involuntary chronic health condition that is highly genetic. As a society, it is important that we recognise and address the core role of psychology when managing obesity. The health service also has a role to play in de-stigmatising messages around obesity to allow positive engagement with people living with obesity especially in initial interactions with primary care.

Parliamentary and NHS guidelines have been produced to inform appropriate communication with and about people living with obesity including using neutral terms like ‘weight’ and ‘body weight’, using person first language such as ‘people with obesity’ or ‘people living with obesity’, using language that is free from judgement or negative connotations and sticking to the evidence to avoid generalisation.

3. Recognise the inflection point brought by disease modifying therapies

The recent development of disease modifying therapies is revolutionising the options for treating obesity. They work by mimicking the action of the gut hormone GLP-1 to effectively suppress appetite and as part of a wider programme of intervention ‘buy the space’ to reset habits. These are far more effective and require less frequent dosing than prior options which worked by preventing dietary fat from being digested with unpleasant side-effects. Currently there are two approved GLP-1 agonists in the UK for obesity that are now available on the NHS as part of the Tier 3 service, Liraglutide and Semaglutide, with more in the pipeline from other pharmaceutical companies.

4. Create a coherent pathway that works for the patient and the system

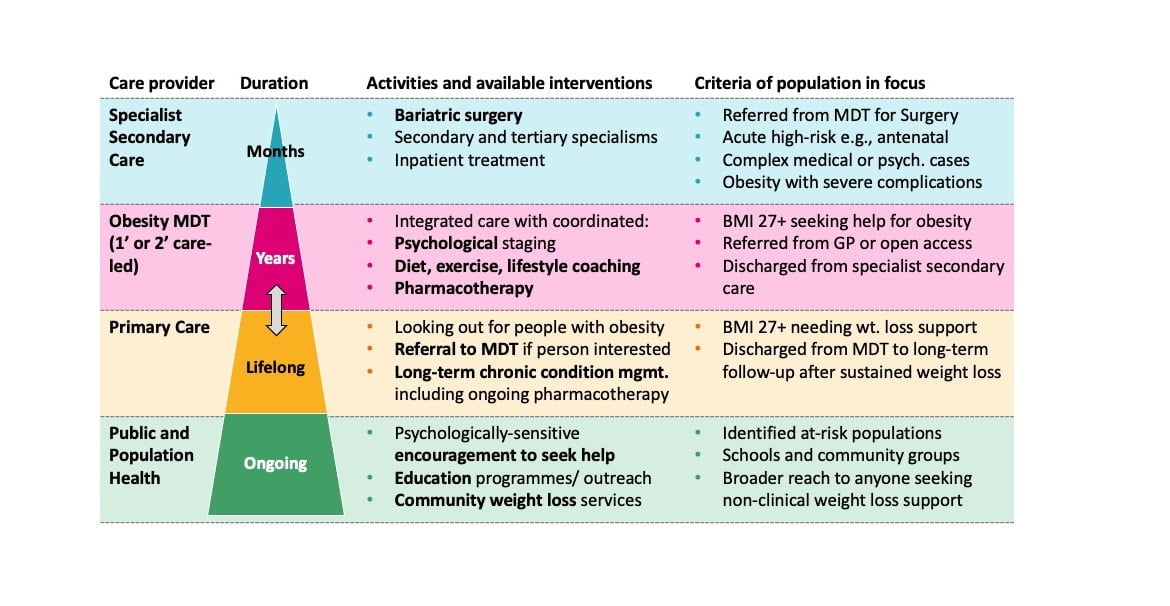

Not so long ago, there was no recognised pathway for type 2 diabetes management. This had to be developed to bring together the various strands of best practice and operational understanding to ensure the right people were seen in the right settings. The result was a pyramid of escalation based on clear criteria. Similarly, to treat obesity effectively at a system-level, a new, more coherent pathway must be designed that works for both the patient and the system. Bringing together the recommendations of the experts we spoke to we would propose a similar pyramid aligned to the 4 tiers, see Exhibit 2. This would need to be effectively integrated within ICS commissioning, provider and place landscapes.

Exhibit 2: Proposed pyramid model of care

5. Use the potential of ICSs to develop the new models of care

A new obesity pathway will only be successful if NHS ICSs are engaged to ensure the pathway works at a local level. The pathway would need to be co-designed with leading clinicians to create exemplar pathways that ICBs can commission and drive. The proof of concept will need to be piloted in carefully selected ICSs that have the bandwidth and desire to focus on innovative care delivery. Ahead of launching a proof of concept, several key elements need to be developed:

- Fund obesity management to match the enormous health economic cost implications

- Learn the lessons of developing sustainable pathways from other complex chronic diseases, like type 2 diabetes

- Train, support and invest in primary care to engage with obesity, becoming the host of the MDT involving all necessary disciplines

- Approve quick access to pharmacotherapy with MDT support

- Fund sufficient access to bariatric surgery in the context of MDT support

- Use data and technology to develop understanding incl. genetics, and real-world effectiveness on a longitudinal basis

- Collect data from operational steps e.g., linking to diet apps, linking to a smart pen to deliver drug doses and linking to national data

- Data standardisation will be required across ICSs through feedback loops with routinely collected data and data sharing from diagnostic and therapeutic devices etc.

[1] Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for eight countries, BMJ

[2] The epidemiology of obesity: A Big Picture, Pharmacoeconomics

[3] Estimating the full costs of obesity, Frontier Economics

[6] NHS England

[7] Tackling obesities: future choices – project report (2007), UK Government’s Foresight Programme

[8] Whole System Approach to Obesity, Public Health England

[10] DHSC Nov 2022

[11] The award-winning integrated obesity service in Rotheram, Primary Care Diabetes Society

[13] Estimating the Full Costs of Obesity, Frontier Economics/Novo Nordisk (2022)

[14] Overcoming Obesity, An initial economic analysis. Note: ‘Social Burden’ defined as direct economic impact and investment to mitigate, McKinsey Global Institute (2014)

[15] The Economics of High Speed 2 – Economic Affairs Committee

[16] Eliminating weight stigma – guidelines for BDA communications, The Association of UK Dieticians

[17] Language matters when talking about weight, NIHR

[18] Language Matters: Obesity, Obesity UK

[21] UK Parliamentary Guidelines: Positive Communication about Obesity