There has been extensive debate about the causes of decline in NHS productivity and soaring spend on acute care services. Indeed, productivity and a new financial foundation has its own chapter in the NHS 10-year plan, with targets of 2% year-on-year productivity gain set for the next 3 years “to urgently resolve the NHS’s productivity crisis”.

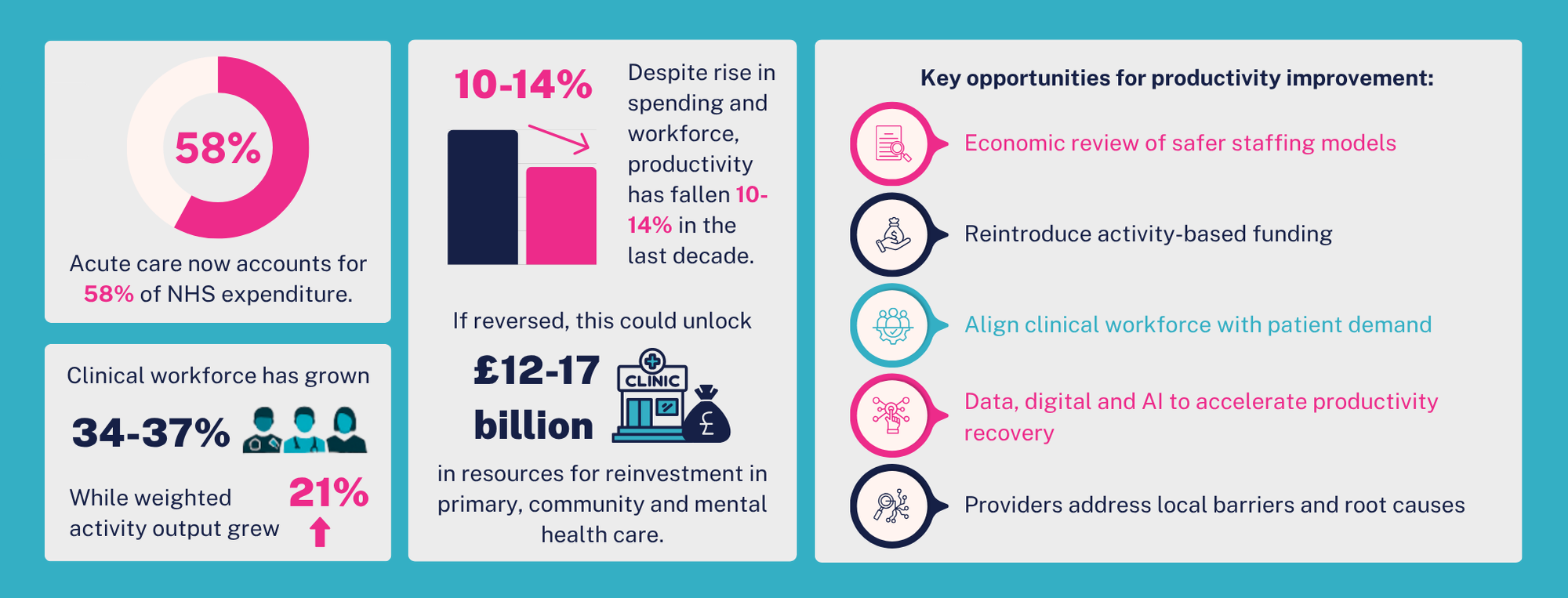

Previous commentary has attributed the productivity decline to the COVID-19 pandemic, for example The Kings Fund cited a 23% decrease in healthcare productivity due to disruption caused by COVID-19. However, our latest analysis shows that the downturn in productivity in acute care started before the pandemic. Productivity increased through the first half of the last decade but started to fall in 2018/19, a year before Covid, as the annual growth rate in clinical staff accelerated to 2.3–3.7 times previous levels. While inpatient care managed to treat rising numbers of patients with a shrinking bed base, outpatient volumes rose steadily at around four times the rate of population growth. Between 2013/14 and 2023/24, acute care productivity dropped by 10–14%, whether measured as weighted activity units per nurse, doctor, or pound spent on the acute sector.

We estimate this drop in productivity since 2018/19 to have cost the NHS from £12bn to £17bn. To put this into perspective, had we backed up the clock to the level of productivity in 2018/19 and spent £17bn less on acute care, we would have reduced the acute share of the NHS budget to 49% from the c. 60% it is today, entirely reversed the “right drift” since 2003 and made funding available for reinvestment in primary care, community care, and mental health to enable care provision closer to home, as laid out in the recent 10 Year Plan.

This second instalment of our Value in Health series – which explores how the NHS can increase the value it delivers and provide better outcomes and greater output with the resources available – focuses in on the productivity challenge in acute care. Acute services represent the largest and fastest-growing area of NHS spending, yet they are also where productivity has declined most significantly over the past decade. This report takes a detailed look at what’s behind that trend, what it’s costing the NHS, and what could be done to reverse it.

What we’ve done – and why

We’ve analysed changes in NHS productivity over the last decade, with a particular focus on the acute sector. Productivity is one way to measure the performance of a sector as it compares the growth in quantity of outputs to the growth in inputs. By understanding how much more the NHS is spending for each unit of output, we can estimate the cost of declining productivity and evaluate priority areas to focus on for recovery. In our analysis, we are measuring productivity in different ways such as weighted activity unit (WAU) per pounds spend, per medical WTE or per nursing WTE. Our full methodology can be found here.

We have focused our analysis on acute hospital care as it is the largest and fastest-growing part of NHS expenditure, now accounting for 58% of spending (The Darzi Report 2024), yet it is also where productivity has deteriorated the most. In contrast, primary care has seen an improvement in productivity, while mental health and community services have broadly maintained productivity levels.

In the analysis, we examined:

- How activity, both inside and outside of hospitals, has changed in the past decade and whether changes in the workforce have been similar

- How NHS productivity in the acute sector has changed and the cost of lost productivity within the acute sector

- The potential structural and regulatory drivers behind falling productivity

We note the following limitations. We have looked at high level publicly available metrics for periods to 2023/24 (the most recent data publicly available) around activity, spend and workforce. While more recent NHS England analysis shows productivity has increased in the period since 2023/24, it is found to remain below pre-pandemic levels. We are unable to infer the exact reasons why output has not increased proportionally with the standard activity metrics that we have used. We have also not examined the level of productivity 10-years ago and opportunities may exist to improve from this baseline level.

A closer look

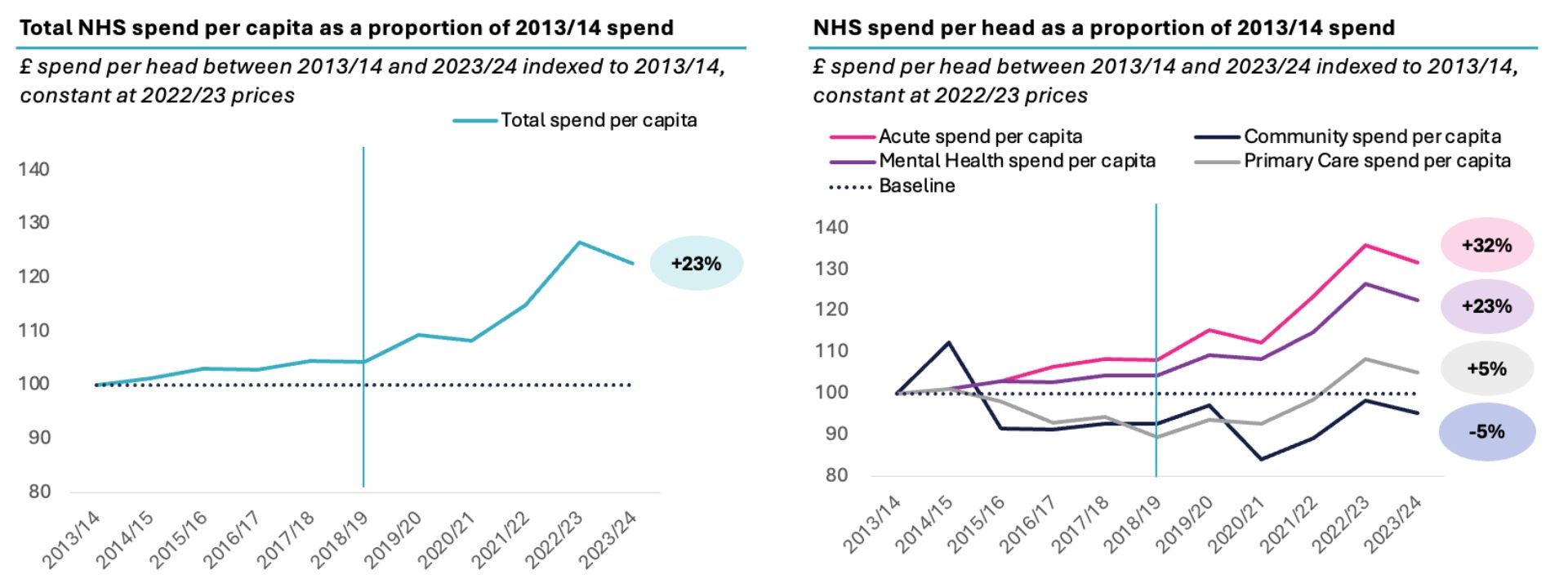

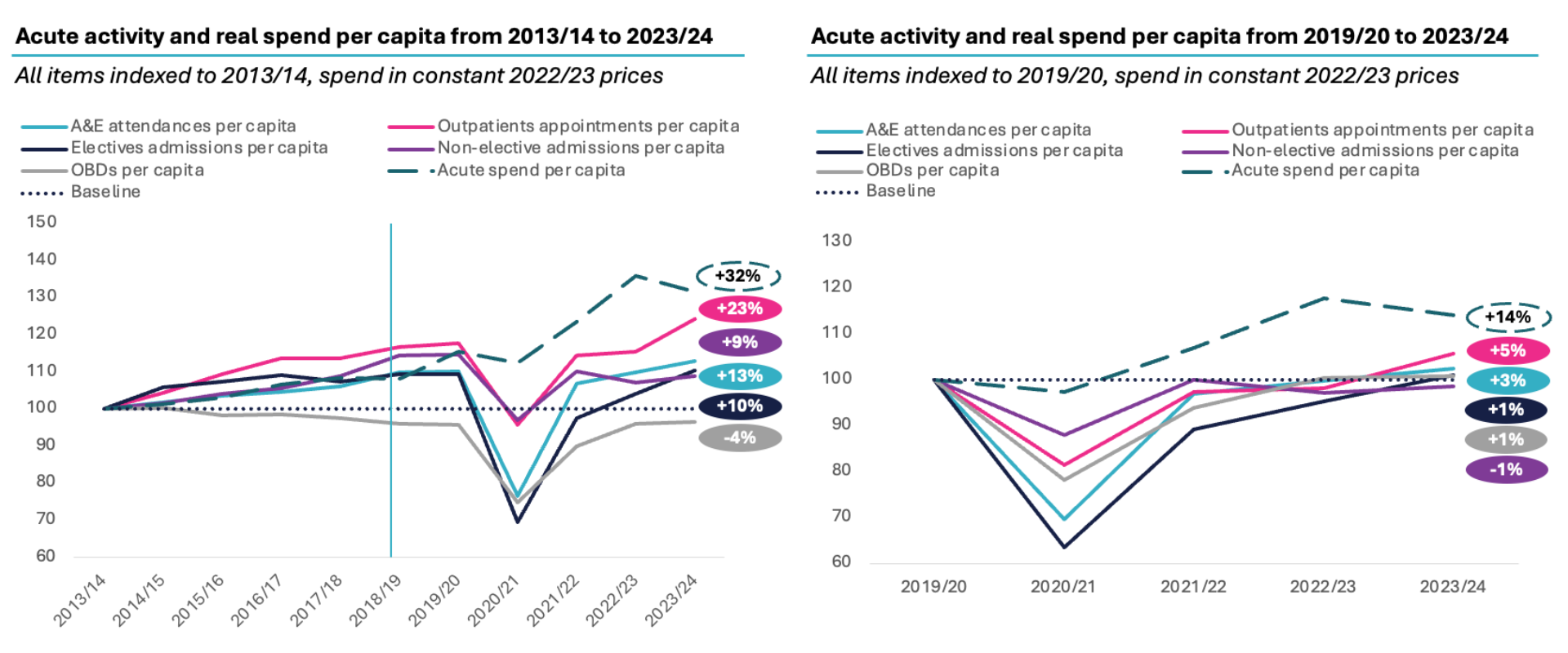

Between 2013/14 and 2023/24, NHS spending per capita increased by 23%. However, this headline figure masks important variation across sectors. The acute sector—already the largest component of NHS spending—grew at an even faster rate, with expenditure per capita rising by 32%, or 1.4 times faster than the NHS overall. In contrast, spend per capita increased by just 5% for primary care, and declined by 5% for community care over the same period.

Source: UK House of Commons Research Briefing: NHS funding and expenditure (2024), Populations data is from ONS. Spend by care setting is taken from Darzi report (2024), 2021/22 – 2023/24 splits are assumed to 2020/21 proportions documented in Darzi. Between 7-10% of spend categorised as ‘Other’ and not attributed to any care setting.

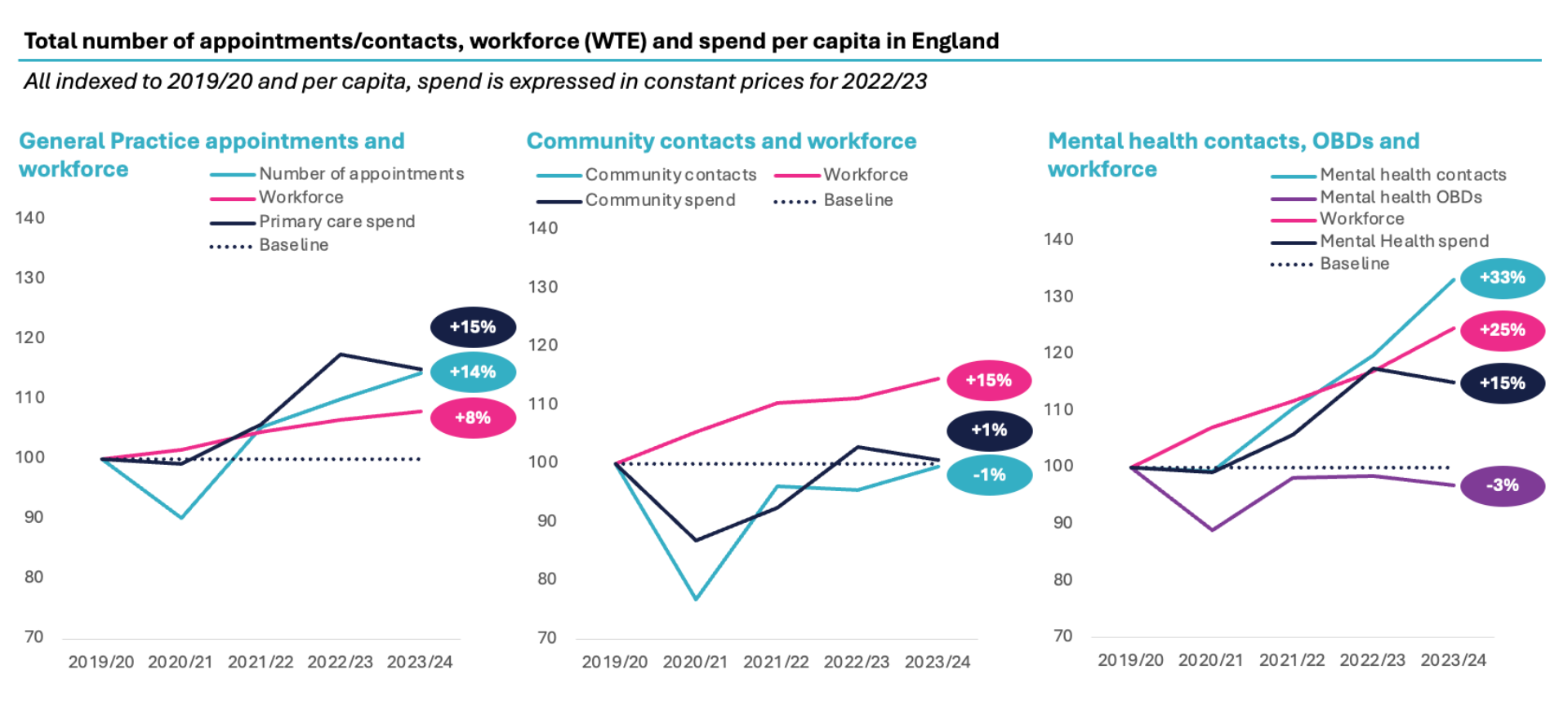

Productivity outside the hospital has kept level or increased from 2019/20 to 2023/24, as activity has increased in line with both spend and workforce. We use 2019/20 as the base year here due to limitations in consistent workforce data for these care settings from 2013/14. This also illustrates that the post-COVID drop in productivity was not universal but largely confined to acute and community settings.

Source: Appointments in General Practices (NHS Digital), General Practice Workforce (NHS Digital) (2019/20 – 2023/24), Mental Health Dataset (MHSDS; NHS Digital), NHS Workforce Statistics (HCHS Mental Health Workforce), Community Care Dataset (CSDS), NHS Workforce Statistics (NHS Digital – mapped to community trusts), CF analysis

In contrast, acute activity generally increased until 2018/19 and fell before Covid, during Covid and has not recovered to pre-Covid levels as real funding per capita outstrips activity.

Source: UK House of Commons Research Briefing: NHS funding and expenditure (2024), Populations data is from ONS. Spend by care setting is taken from Darzi report (2024), 2021/22 – 2023/24 splits are assumed to 2020/21 proportions documented in Darzi. Between 7-10% of spend categorised as ‘Other’ and not attributed to any care setting. NHS A&E attendances, NHS Outpatients appointment dataset, NHS Emergency and Non-elective admissions, NHS Hospital Admitted Patient Care and Adult Critical Care Activity, NHS KH03 Occupancy Dataset.

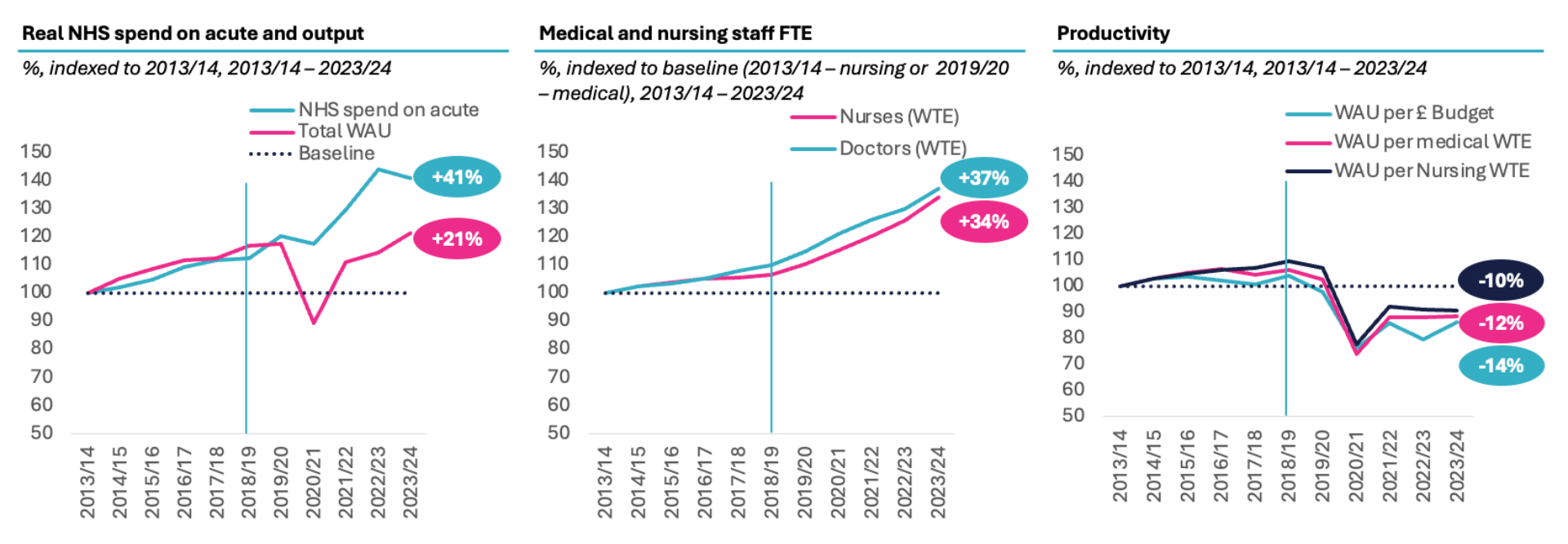

Acute productivity has fallen from 2013/14 to 2023/24, as real spend has grown 41%, while weighted activity output grew 21% and workforce 34-37%.

The downturn in acute productivity appears to have begun before the COVID-19 pandemic. From 2018/19 onwards, a marked shift occurred: activity began to plateau and even decline, while the size of the clinical workforce – particularly doctors and nurses – expanded at an accelerated rate.

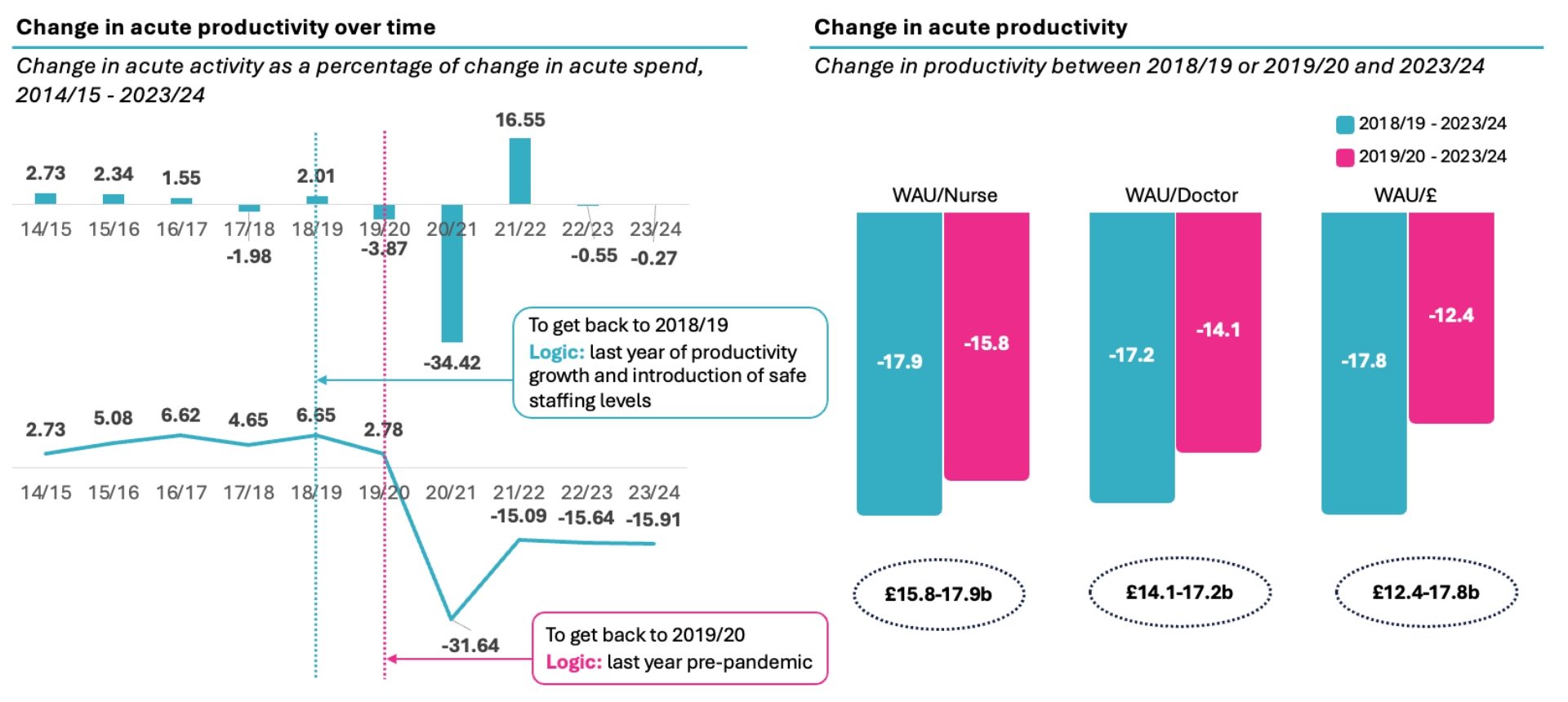

This divergence points to a productivity decline in the range of 10–14%, depending on whether productivity is measured by comparing weighted activity units (WAUs) to spend, medical WTE or nursing WTE.

Source: CF Analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics, KH03, ONS, Unit Cost of Healthcare, NHS workforce statistics, NHS Funding and Expenditure, Darzi report, Hospital Episode Statistics (A&E Attendances & Emergency Admissions, Hospital Outpatient Activity, Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity), KH03 Bed Occupancy (Average Daily Available and Occupied Beds Timeseries), ONS England population, Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2023, NHS Hospital & Community Health Service (HCHS) – Staff in NHS Trusts and other core organisations (NHS workforce statistics), Parliamentary Briefing (NHS Funding and Expenditure (2024), Figure VIII.1.1 Darzi, Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England

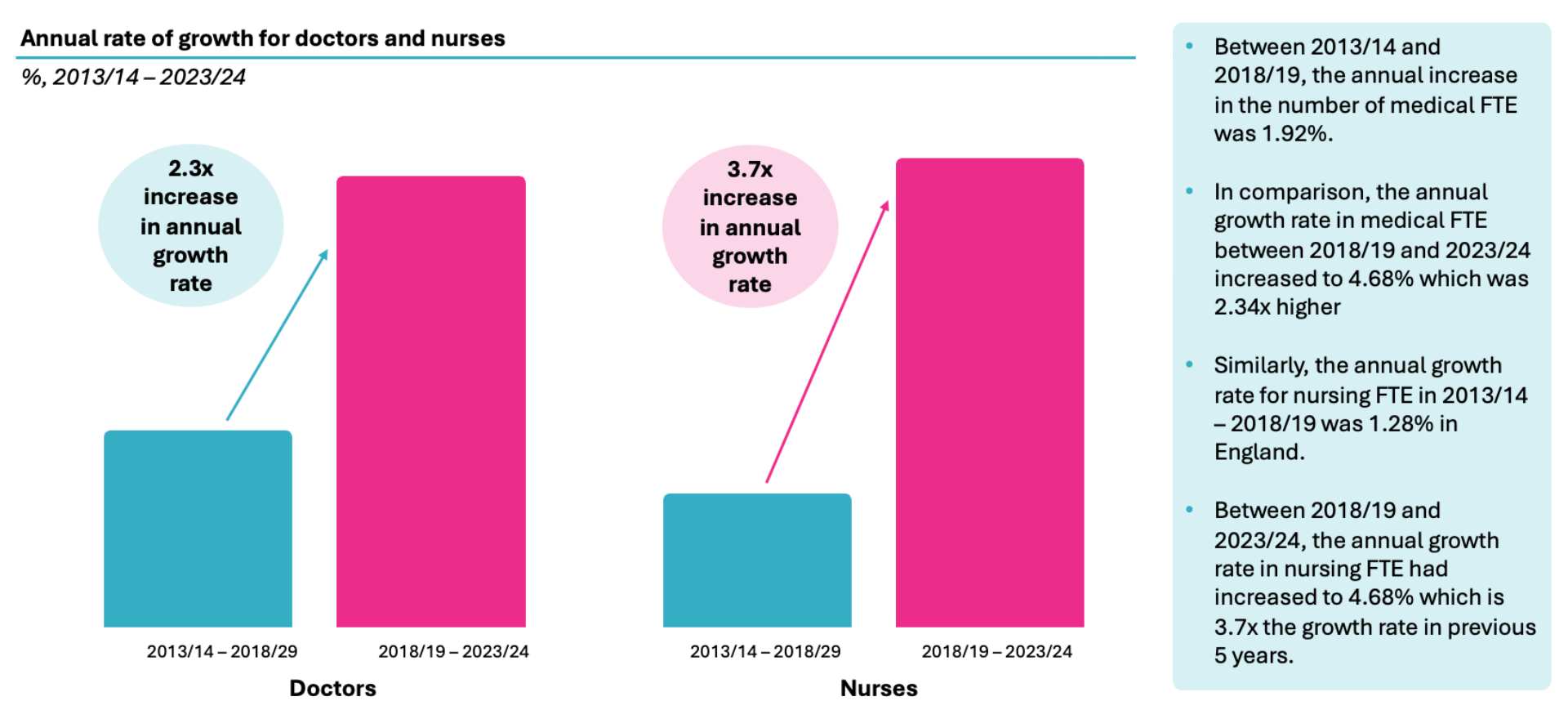

Between 2013/14 and 2018/19, the annual growth rate in the number of medical full-time equivalents (FTEs) was around 1.9%, which increased by 2.3-fold to 4.7% from 2018/19 to 2023/24. Similarly, the annual growth in nursing FTEs jumped from 1.3% to 4.7% – a 3.7-fold increase.

Source: NHS Workforce Statistics (Nursing Workforce), ONS (Medical Workforce)

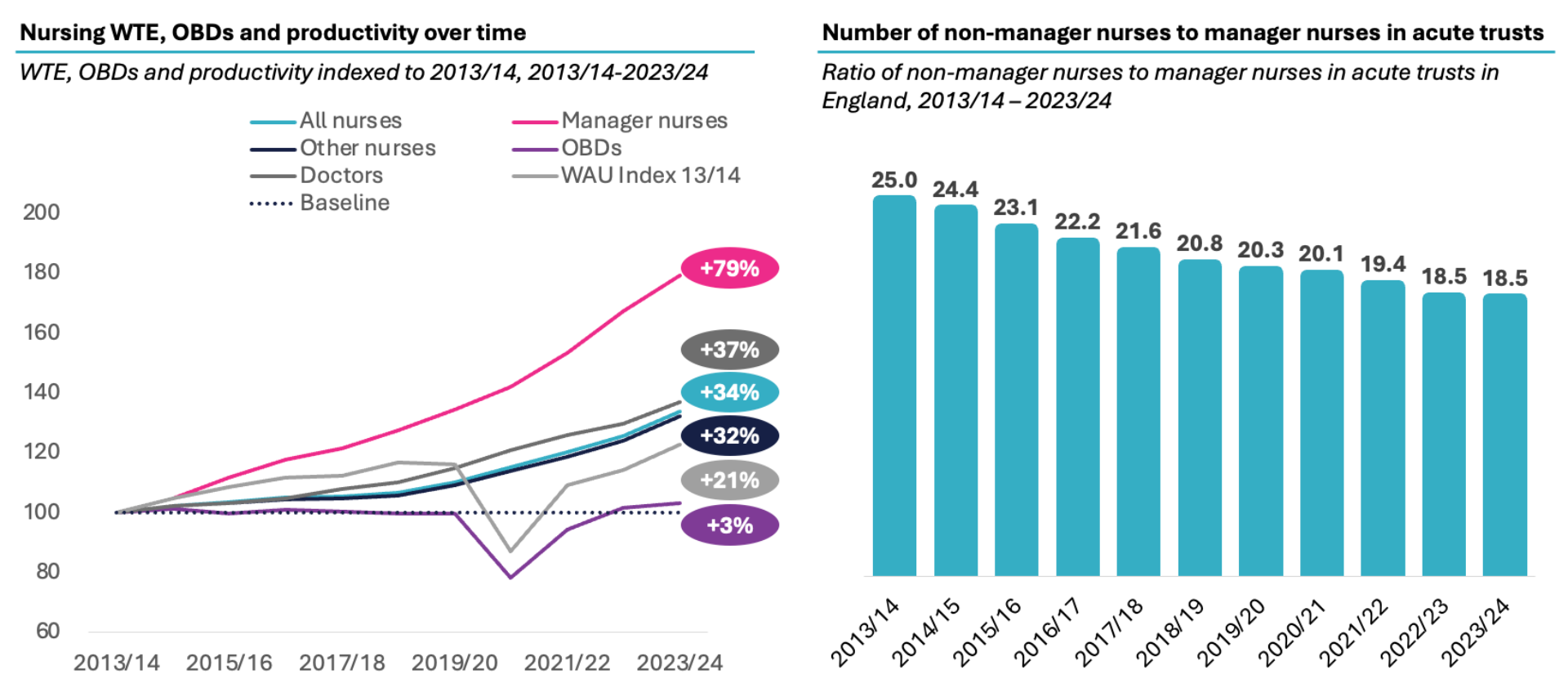

Additionally, the number of modern matrons and nurse managers has increased significantly, with an associated fall in the ratio of non-manager to manager nurses.

Source: KH03 Bed Available and Occupancy (NHS Statistics), NHS Workforce Statistics. Note: manager nurses include: Nurse Managers and Modern Matrons as defined by NHS England

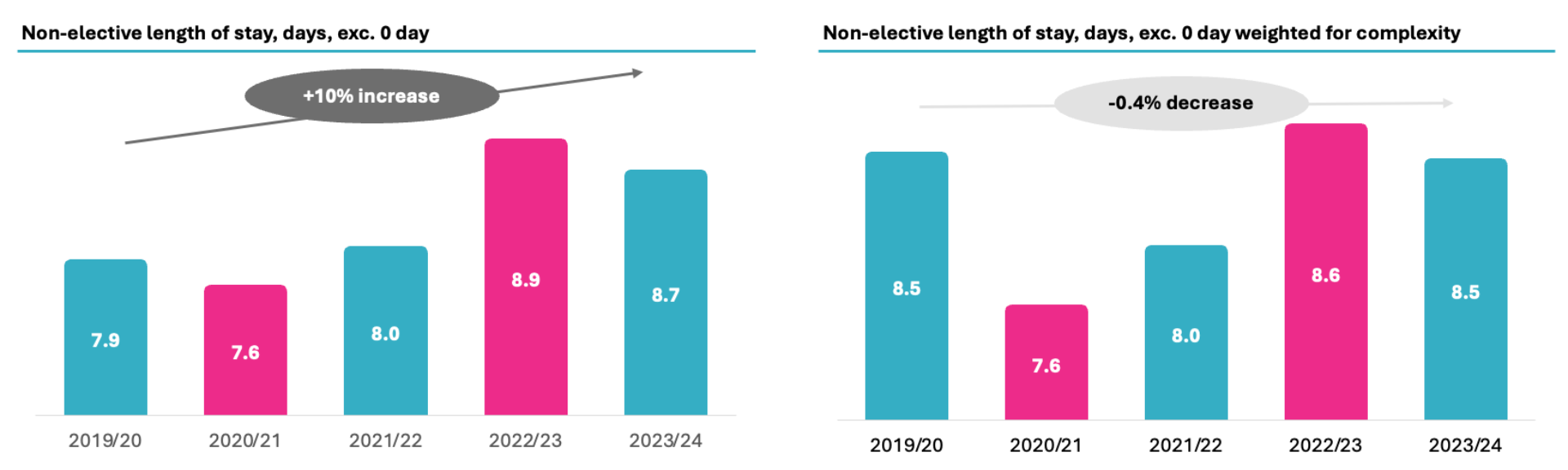

We also found that average length of stay has increased in last five years, but this change can be wholly attributed to the increase in complexity of spells—which is already accounted for in WAUs – and hence is not responsible for lost productivity.

Source: HES, CF analysis

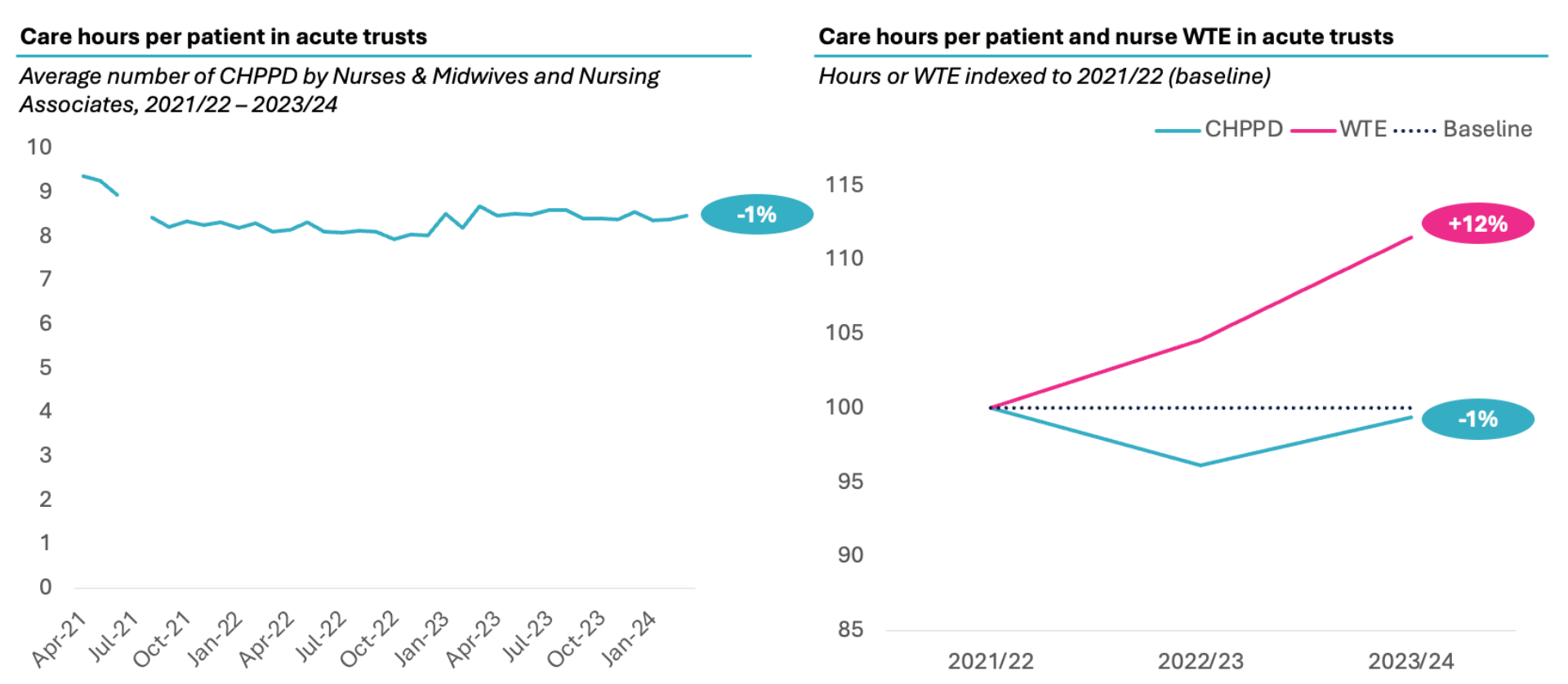

Even when measured on a per-patient basis, care delivery has remained largely static. The number of care hours per patient day (CHPPD)- a core measure of nursing productivity – has not increased, despite a 12% increase in the nursing workforce between 2021/22 and 2023/24. This suggests a considerable and sustained erosion in productivity.

Source: Care hours per patient day (CHPPD) data (NHS Digital), NHS Workforce Statistics, CF analysis, Notes: Acute providers defined as per the list of trusts and foundation trusts in the TAC accounts

CF’s analysis shows this productivity loss amounts to £12bn to £17bn since 2018/19.

The decline of productivity in acute care started before Covid in 2019/20. Therefore, we use 2018/19 as a benchmark in our analysis below to more accurately capture the loss of productivity and the benefits from productivity recovery. Between 2018/19 and 2023/24, acute care productivity dropped by 17-18%, whether measured as weighted activity unit per nurse, doctor or pound spent on the acute sector.

The loss in acute productivity between 2019/20 and 2023/24 is estimated to have cost approximately 12-18% of the acute budget and is equivalent to £12-17bn per year.

Source: CF Analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics, KH03, ONS, Unit Cost of Healthcare, NHS workforce statistics, NHS Funding and Expenditure, Darzi report, IBID.

If we backed up the clock to the level of productivity in 2018/19 and banked the 17-18% productivity gain, the £17bn reduction in acute spend would reduce the acute share of the NHS budget to 49% – significantly below almost 60% share today. In other words, it would entirely reverse the “right drift” since 2003 and make an “acute productivity dividend” of £17bn available for reinvestment in primary care, community care, and mental health to enable care provision closer to home.

What is causing this decline?

This deterioration in productivity cannot be attributed to a single cause. Several systemic factors are likely at play. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruptions to elective care, chronic disease management, and diagnostic pathways. Many patients deferred care, leading to later-stage presentations and higher acuity.

At the same time, policy changes have had significant unintended consequences. The introduction of safer staffing guidance, including the formal endorsement of acuity-based safer staffing tools and CHPPD as a principal national measure in 2018/19, while aimed at improving care quality, appear to have triggered a sharp and sustained increase in nurse recruitment – without a matching rise in output. This is also a key finding in the recent review by Dr Penny Dash of patient safety across the health and care landscape, which finds that there has been a shift towards safety (vs other areas of quality of care) over the last 5 to 10 years, with considerable resources deployed, but relatively small improvements seen. The review goes on to say that the combination of regulatory recommendations, which often include increases in staffing levels to direct patient care staff and supervisory staff, and ‘Safe staffing tools’ to set out the expected staffing levels have potentially contributed to the considerable growth in hospital staffing and funding over the last 10 years.

Meanwhile, the suspension of Payment by Results (PbR) has weakened the link between activity and funding, removing a key incentive for efficiency. Inconsistent clinical coding, particularly in areas like same-day emergency care (SDEC) and zero-day admissions, may have also masked real activity levels and contributed to misleading productivity metrics.

There are also structural barriers to recovering lost productivity. Hospitals face growing difficulty in discharging patients in a timely way, due in part to limited capacity in community and social care. Rising bed occupancy leaves little flexibility to manage flow, while ongoing measures introduced during the pandemic – such as infection control protocols and cohorting – continue to constrain operational efficiency. At a management level, high turnover of senior leaders has eroded institutional knowledge and capacity for long-term improvement. And the workforce itself is under strain, with increased sickness, industrial action, and declining morale impacting day-to-day productivity.

In contrast, primary care – where funding remains linked to outcomes and activity through mechanisms like the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) – has maintained high productivity. It also benefits from stronger data systems and more transparent links between inputs and performance. Community and mental health services suffer from poor-quality data and lack any meaningful link between funding and activity but at least appear to have avoided the deep productivity decline seen in acute hospitals.

Opportunities for productivity improvement

There are several actions that can be taken to reverse the trend and recover clinical workforce productivity at the system or provider level, some of which are:

Ultimately, our analysis reveals that acute care productivity has undergone a substantial and sustained decline. Unless this is addressed, continued investment into the acute sector risks delivering diminishing returns – while starving other parts of the system better equipped to manage rising demand. If the NHS had maintained 2018/19 levels of acute productivity, the resulting £17 billion “productivity dividend” could have funded a fundamental shift towards prevention, primary, and community-based care.

Reversing this trend is essential not only for financial sustainability, but for building a health service that delivers higher quality care to patients and taxpayers as timely and as close to home as possible.

Coming up next

In the next part we will take a closer look at the unmet needs in chronic diseases and how to close the gap in the quality of care. If you missed the first part in this series, click here.

If you would like to discuss this report in more detail, please contact our team.

About CF

CF is a leading consultancy dedicated to making an enduring impact on health and healthcare. We work with leaders and frontline teams to improve health, transform healthcare, embed life science innovation and boost growth through investment. With unmatched access to UK healthcare data and award-winning data science expertise, our team are a driving force for delivering positive and meaningful change.

About the authors

Ben Richardson

Ben Richardson is a Managing Partner at CF, leading Life Sciences and Data Innovation. With two decades of experience, he has worked with health systems and life sciences companies globally, focusing on strategy, transformation, and development. Ben has contributed to primary care, diabetes, cardiovascular, cancer, mental health, and population health management. Since 2014, he has helped CF become an award-winning healthcare company in management consulting and data services.

Catherine Skilton

Catherine is Managing Partner at CF, leading Health Systems. She has over 20 years’ experience in health and care consulting, working with NHS Boards to deliver sustainable, digitally enabled change programmes across finance, operations and quality, as well as the enabling infrastructure and organisational changes. Catherine is a Fellow Chartered Accountant and practicing ICAEW member with deep expertise in financial recovery and system-wide transformation.

Yemi Oviosu

Yemi is a Senior Manager at CF with a PhD in Cardiovascular Biochemistry, specialising in strategy and scaling innovation for healthcare and life sciences clients. He focuses on evaluating and implementing digital technologies that enable population health management and driving sustainable, enterprise-wide transformation. His unique blend of scientific insight and technology-strategy expertise helps clients accelerate innovation, de-risk investments, and improve patient outcomes.

With special thanks to Elise Kearsey, Beena Mistry, Colette Russell, Lali Sindi and Gauri Patel.