Boris Johnson’s resignation this week will no doubt raise the profile of his ‘40 new hospitals’ pledge at the start of his term in office. This combined with Amanda Pritchard highlighting the need to ’right-size the bed base … Because there is a proportion of patients who are sick and need to be, in our current model, in beds — and that’s not the wrong thing for them’[1], at the NHS Confederation Conference a couple of weeks ago, bring into focus why we should be worried about the lack of capital funding for the NHS.

The historic deficit has resulted in environments that are not fit for purpose

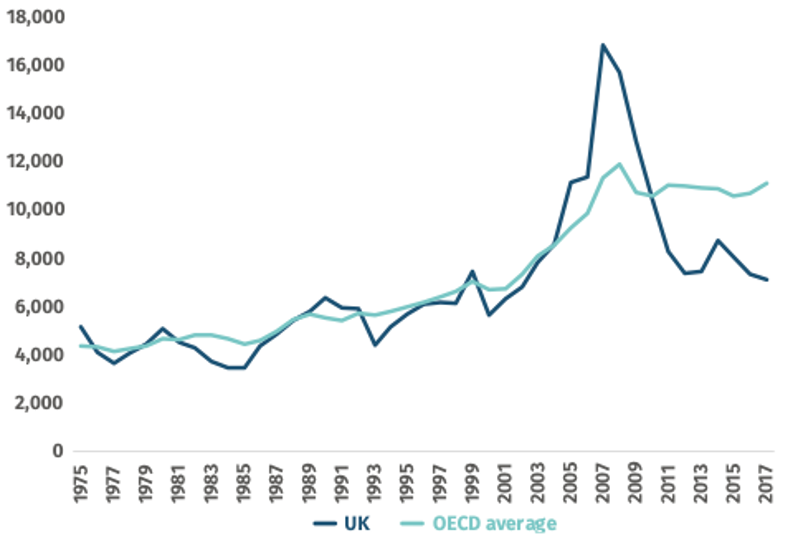

The UK has historically underinvested in capital as shown by analysis conducted by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR); relative to similarly developed nations (OECD members) the United Kingdom has underinvested capital by £100bn since 1975[2], as compared to the average. A consequence of this long-term lack of capital investment is that this is now impacting on patient care and staff. A startling 43% of NHS buildings are over 30 years old, with 18% of properties pre-dating the NHS’s foundation in 1948, placing additional stress on capital budgets[3]. Backlog maintenance – the cost of restoring deteriorated assets to an acceptable level for usage – had reached £9.2bn by 2020/21, including £4.6bn to fix issues posing a ‘high’ or ‘significant’ risk to patients or staff[4].

Exhibit 1: Capital formation in the UK compared to the OECD average ($m in constant spend)[5]

Source: IPPR 2019

The only period when NHS capital investment outpaced the OECD average was during the 2000s, enabled by the use of PFI, since recognised as a costly financing model relative to crown debt.

A previously efficient bed base is inadequate and inefficient to meet need

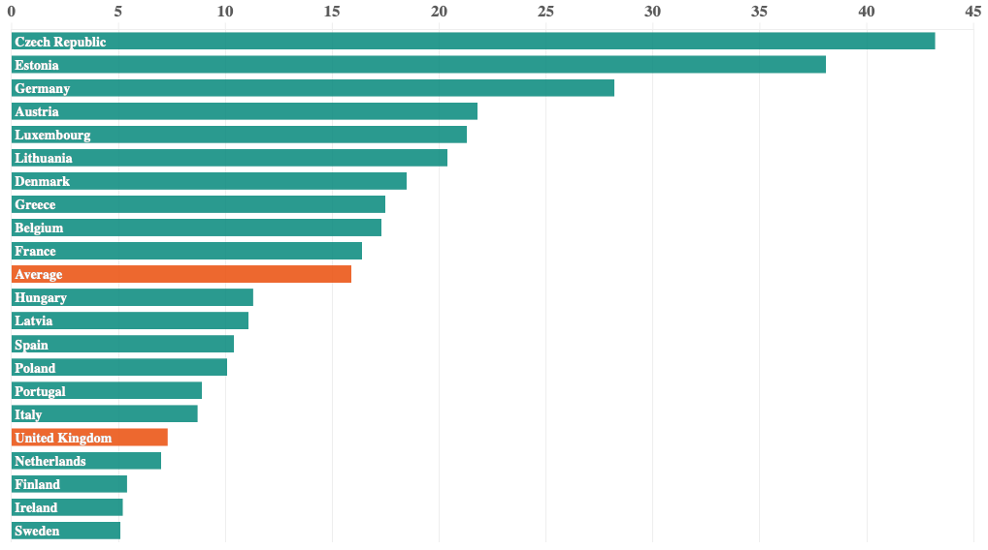

The NHS has a lower hospital bed capacity than its OECD peers with 2.4 hospital beds per 1,000 population, compared to an EU OECD average of 4.6[6]. At the recent NHS Confederation conference, NHSE Chief Executive, Amanda Pritchard, argued that, whilst it has previously reflected a certain level of efficiency, the low bed-base in the NHS is now a source of ‘inefficiency’ due to insufficient capacity[7].

Exhibit 2: critical care hospital beds per 100,000 inhabitants: UK and OECD EU nations[8]

Source: BMA 2022

A low bed-base, combined with slow discharges, can be linked to backlogs in both elective and emergency care; a lack of space for incoming patients leading to delays and cancellations. These delays affect patients and their families who need treatment for conditions that are disrupting their lives. People suffer longer, with recovery and rehabilitation longer and outcomes potentially worse. In the worst cases, patients with relatively mild conditions waiting long periods for elective care can see their conditions exacerbated and even, in some cases, become emergency patients. Not only is this extremely stressful and impacts on the mental health of patients, but it places a greater burden on the wider system and increases costs.

The working environment for staff is also key as research shows that a poor-quality environment directly affects staff satisfaction, which is linked to patient outcomes[9].

It is also clear that additional pressure on beds from Covid-19 patients with infection control measures has further reduced hospital bed capacity, contributing to considerable increase in waiting lists that are now incompatible with public and political expectations of the NHS.

The historic underinvestment in NHS assets has directly impacted on patient outcomes.

Early 2020 sparked hope with the promise of 40 new hospitals

Boris Johnson responded to numerous challenges about the lack of investment in NHS Estate and infrastructure with the promise that 40 new hospitals would be built by 2030, with an option to expand the programme to a further 8 sites.

The New Hospitals Programme was designed to help redress this capital deficit. By building as many as 48 hospitals by 2030, England’s health infrastructure would be updated for the 21st century, reducing the historic deficit and meet the consistent calls from NHS leadership for a ‘capital settlement’ to support improvements in the estate.

Insufficient investment risks this becoming reality

However, recent developments have dampened enthusiasm. Capital availability is again being severely restricted, with the Treasury tightening the purse strings in the wake of high spending throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

The 2021 Spending Review confirmed £4.2bn would be made available for the period 2022/23 to 2024/25 to progress capital improvements[10], including £3.7bn for the New Hospitals Programme[11] but this has widely been seen as insufficient, with Lord Simon Stevens, former Chief Executive of NHS England, dismissing this as insufficient in a House of Lords debate, saying ‘that does not buy you 40 hospitals’[12].

Eight ‘pathfinder’ Trusts, meant to be trailblazers for the programme, now are at risk of being able to complete construction by 2026-28, with current years project management budgets being considerably lower than planned. For example, Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals Trust requested more than £8m this year, but only £1m was made available[13], risking project failure.

Exhibit 3: Epsom and St Helier University Hospital[14]

Source: Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust

The difficulty of the early trailblazer projects in getting off the ground has worrying implications for the project in its entirety and real concerns that there will be insufficient capacity to meet the need and the timeline of 2030 moving beyond reach.

The lack of capital is compounded by the unprecedented rising construction costs in the current financial climate, rising inflation and the impact of the war in Ukraine with the Building Cost Information Service Materials Cost Index forecasted to reach nearly 18% by the end of the year[15].

Capital is needed to support the promised reduction in waiting lists

Nearly 6.5m patients are currently waiting for elective care, more than one in ten of the population and a number expected to grow considerably over the coming years.

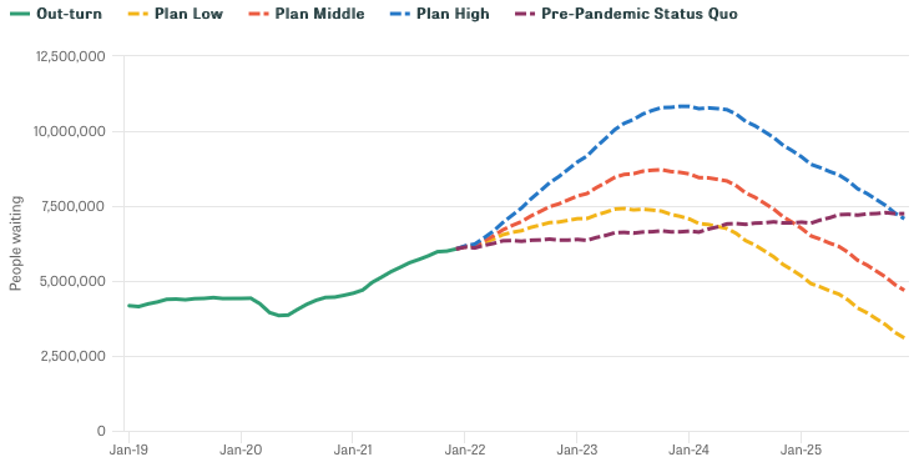

Modelling from the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests that if the NHS successfully increases capacity by 30% by 2024/25, as planned, the waiting list will not be reduced to pre-pandemic levels until May 2024 in even the most optimistic scenario[16]. One bottleneck for reducing the waiting list is the availability of beds.

Exhibit 4: Waiting list scenarios 2022 to 2025[17]

Source: IFS 2022

Our analysis shows that to expand capacity enough to reach even this most optimistic target would cost between £17.1bn and £26.4bn of capital investment in General and Acute beds at current bed utilisation, whilst reducing utilisation to safe levels[18] and increasing capacity enough could cost between £23.3bn and £35.9bn[19].

Capital is important but reform is even more important

Despite the immense pressure, the ageing of hospital infrastructure and the political appeal of focusing new money on a new hospital programme, NHS leaders would nonetheless challenge whether this represents the overriding priority for investment given the reality of such scarcity of capital.

The continued underfunding of NHS Estate and significantly less beds than OECD peers do hold back NHS performance and impact on outcomes. However, the focus should not be about allocating those scarce resources to maintaining the status quo. It is not just acute bedded capacity that is needed but also Mental Health, Community and social care capacity as well as fit-for-purpose primary care facilities. The drive for transformation and recognition that often the right bed for a patient is in their own home must remain at the centre of recovery and restoration.

In a world of tough choices, it is important for the NHS to reform and invest in community and primary care aimed at meeting care and treatment needs locally and without unnecessary hospital admissions and excessive stays needs to be the overwhelming priority for the NHS.

A paper published by the IPPR in 2021[20], using CF analysis, illustrates that the British care system currently over-uses acute care for the elderly and infirm, when community care would be more appropriate.

At CF, we are experienced in helping NHS partners develop the appropriate capacity to meet current and future demand, through both organic efficiency improvements and the most appropriate capital investment. We know that the historic lack of capital investment often pushes providers to seize any opportunity for capital investment despite the potential for more tailored solutions through improved models of care.

The consequence of the issues faced by the NHS at present is a perfect storm. Lengthening waits and clinical outcomes combined with higher capital costs threaten the NHS consensus. We have already seen the early signs of a concerted campaign within some sections of the media to undermine and blame the NHS for its current struggles.

There is no doubt that capital is urgently needed; the questions remain where this will come from at the levels required to provide the infrastructure to enable a fit-for-purpose and fit-for-the-future health system. This needs to reflect embracing the changes in models of care as set out in the Long Term Plan and a collaborative and collective focus on care being provided in the right place and that the best bed is one at home and not one in a hospital. A capital investment cannot succeed without properly implementing and supporting the appropriate care models. The public need to embrace this and the newly developing ICS need to work with all partners and stakeholders to make the change.

[1] NHS England reviewing bed capacity, HSJ, 2022

[2] C. Thomas, The ‘make do and mend’ health service: Solving the NHS’ capital crisis, IPPR, 2019

[3] Why the estate matters for patients, NHS Property and Estates, 2017

[4] S. Anandaciva, The latest on the NHS estate, The King’s Fund, 2021

[5] C. Thomas, The ‘make do and mend’ health service: Solving the NHS’ capital crisis, IPPR, 2019

[6] NHS hospital beds data analysis, BMA, 2022

[7] NHS England reviewing bed capacity, HSJ, 2022

[8] NHS hospital beds data analysis, BMA, 2022

[9] J. Dawson, Links between NHS staff experience and patient satisfaction: Analysis of surveys from 2014 and 2015, NHS, 2018; C. Borrill et al., The Relationship between Staff Satisfaction and Patient Satisfaction, Aston Business School, 2015

[10] Capital Guidance 2022 to 2025, NHS, 2022

[11] PM confirms £3.7 billion for 40 hospitals in biggest hospital building programme in a generation, DHSC, 2020

[12] Hansard HL Deb. vol.822 col.869, 25 May 2022

[13] Fears of delay to flagship ‘new hospitals’ after funding cut, HSJ, 2022

[14] Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust

[15] How the rise in material costs is damaging the UK’s construction industry, Investment Monitor, 2022

[16] G. Stoye et al., The NHS backlog recovery plan and the outlook for waiting lists, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2022

[17] G. Stoye et al., The NHS backlog recovery plan and the outlook for waiting lists, Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2022

[18] 85% bed utilisation is widely recognised to be the safe level: A. Bagust et al., Dynamics of bed use in accommodating emergency admissions: stochastic simulation model, BMJ, 1999; NHS Providers, Bed occupancy rates hit record high, 2017

[19] NHS Digital KH03 Data, Oct – Dec 2019 & Jan – March 2022; Typical UK Construction Costs of Buildings, Cost Modelling, 2022,; K. Fricke, 8 Considerations For Benchmarking, Healthcare Design, 2017; Delivery Plan for tackling the Covid-19 backlog of elective care, NHS, 2022

[20] C. Thomas, Community First Social Care – Care in places people call home, IPPR, 2021