Community healthcare keeps people independent as they get older, and in doing so makes the NHS more efficient and effective. But how can national and system leaders realise their potential? In the second of our two-part series, we look at how a clear community offer enables equitable service provision for all residents, relative to need – and drives NHS and wider public service efficiencies over the long term.

We know that community healthcare plays a truly vital role in our society, enabling older people and those with complex conditions to live independently and safely at home. Services such as district nursing, community therapy and rapid response teams provide a seamless continuum of care for those who need it, delivered directly in homes or community locations.

This integrated approach – and the focus on keeping people safe and well at home – minimises unnecessary admissions and enables people to return home from hospital more quickly. In addition to the direct benefit to people’s health, the ‘home is best’ focus reduces the risks associated with a longer stay in hospital.

As such, community healthcare acts as the linchpin for supporting effective system flow. In addition to the moral argument for investing in these services, our recent research has shown that greater spending on community healthcare could make the NHS more efficient, through lowering the overall total cost of care requirements.

How can investment in community nursing be improved? In this article we address this, through a case study that shows what systematic investment in community healthcare looks like at a local level.

Definition and funding of community services – the current situation

Community services encompass a very wide range of services. There is no national contract or definition for this healthcare, with different Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) commissioning different provision, and even greater variation at a place level within each ICS. Spending is almost entirely at the discretion of local leaders, with the evidence showing that in general, there is no relationship between community spend and existing measures of community need.

Our experience of working with local systems has revealed that uneven investments in community services leads to big differences in healthcare access and health outcomes for people living in different areas. The waiting times for appointments and treatment can also vary considerably. This postcode lottery not only puts some patients at a clear disadvantage – it also perpetuates a highly inefficient use of resources. Resolving these problems through a clear service offer can both improve patient care and generate savings over the longer term, as our case study shows.

Case study – North Central London

North Central London (NCL) Integrated Care Board was formed through a merger of five legacy London clinical commissioning groups. Following the merger, a decision was taken to review community and mental health services and to create a strategy for the future.

The programme of work was undertaken through engagement with frontline staff, residents and stakeholders. It involved:

- Reviewing current community health and mental health services across the geographical area.

- Designing a new core offer – a description of the services all residents should have access to.

- Conducting an impact assessment of the core offer.

- Engaging with stakeholders to encourage buy-in to the offer.

- Developing implementation plans.

The review included understanding the number of appointments being carried out by providers in each borough, the size and shape of the workforce and the amount of money being spent. Hundreds of colleagues also gave their feedback and views on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and challenges of the services involved.

A powerful case for change

NCL’s review found that historic differences in funding amongst the former commissioners had led to considerable variation in the way community and mental health services were delivered. For example:

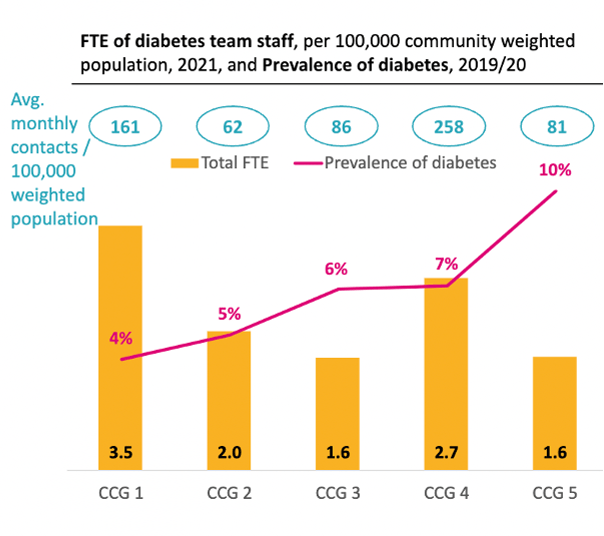

- Enfield had over twice the prevalence of diabetes as Camden, but half the number of staff supporting people with diabetes.

- Children in Barnet wait 20 more weeks than children in Camden for initial speech and language therapy assessments.

- Black people are disproportionately admitted to mental health inpatient beds; Black people accounted for 18% of people in contact with community based mental health services, but 27% of inpatient admissions.

- NCL residents with severe and enduring mental illness are 4 to 6 times more likely to die before the age of 75, but only 20% of them receive a yearly physical health check.

- In Haringey, £98 per head was spent on community health services vs £192 per head in Islington.

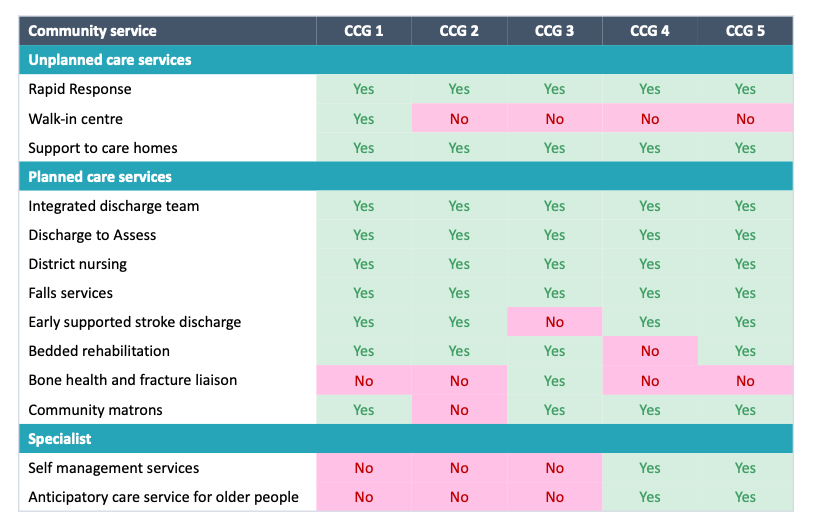

The following graphs highlight the analysis the team undertook:

Diagram 1: variation in community health service offer across legacy CCG areas – click to enlarge

Diagram 2: variation in level of diabetes resource versus need across the legacy CCG areas – click to enlarge

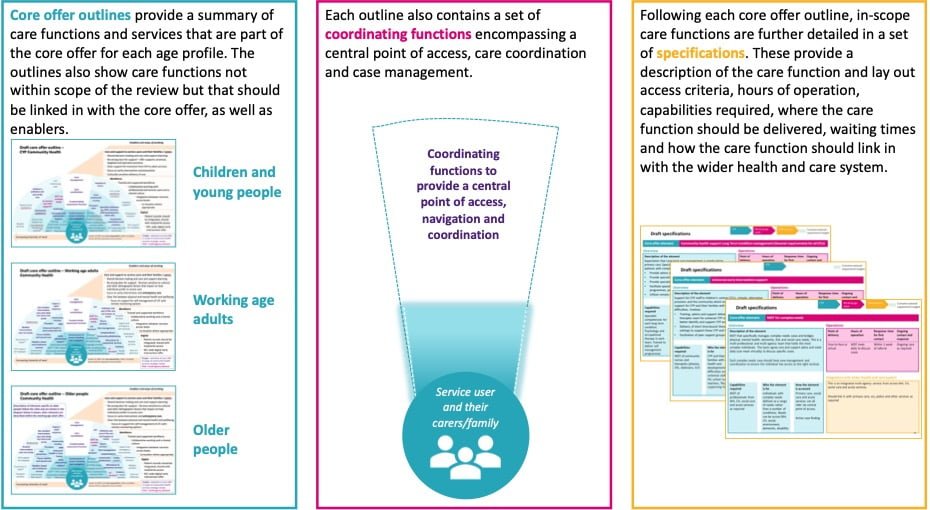

System leaders agreed that this level of variation was something that needed to be addressed as a priority. Having set out the case for change, NCL worked closely with stakeholders to design the core offer, drawing on case studies and national guidance, alongside local experience and examples of best practice. The result was a bespoke core offer that described the community and mental health services that should be universally available to all NCL residents, with clear descriptions of:

- Response times.

- Criteria for people to access services.

- Requirements for services to meet national quality guidelines.

- Workforce capabilities.

The offer also described the coordinating functions required, including a central point of access and case management.

Diagram 3: components of NCL’s core offer – click to enlarge

The next stage involved understanding the potential impact of implementing the core offer. The team at NCL assessed the benefits and impacts for residents, as well as the financial impacts to the system. Following extensive testing, the assessment was presented to system colleagues, encouraging buy in to the new strategic direction. After securing support, two implementation plans were drawn up – one for Community Services and one for Mental Health Services.

Outcomes of the NCL community offer to date

Following the work, NCL committed to funding the new community and mental health service offer, and has already made several significant investments to equalise community services in the first year, including:

- £5.4m investment in virtual wards, expected to avoid 13,000 bed days annually.

- £1.95m in Enfield Year 1 interventions, expected to avoid more than 2,000 bed days annually.

- £1.45m in Haringey Year 1 interventions, expected to avoid more than 500 bed days annually.

- £0.5m in Haringey Year 2 interventions, expected to avoid more than 1500 bed days annually.

- £0.8m in Barnet Year 2 interventions, expected to avoid more than 6700 bed days annually.

- £0.4m in NCL-wide Year 2 interventions, expected to avoid more than 2700 bed days annually.

A benefits realisation framework has now been established, including community and mental health outcomes frameworks, as well as service level highlight reporting. These have demonstrated improvements to population health outcomes and delivery of the core offer ambition across NCL. The improvements include expanded hours of operation, improved staff and skill mix, increased activity, and improved response times and waiting times.

Agreed funding sources for year three of the programme include acute contributions related to system savings from non-elective demand growth mitigation, as well as savings from a collaborative provider productivity exercise. NCL providers are collaborating on identifying shared productivity opportunities and have jointly developed a methodology for quantifying productivity initiatives.

NCL is now on track to deliver equitable and high-quality community and mental health services for residents over the next five years.

How local ICSs can seize the opportunity to achieve greater efficiency

1. Review current community healthcare across the local system

This includes reviewing how community healthcare services are currently commissioned and funded, what service specifications are in place, what the level of need is within each service, and what the healthcare needs of the local population are. This work will highlight disparities across the local area.

2. Review current community healthcare funding

The level of local need versus current funding for community healthcare services could be assessed at this point. Does the funding match need? If not, what level of investment would provide a consistent level of resource relative to need? In all likelihood, this could result in an overall increase in funding for community healthcare, although our research shows there is a strong business case for this through an associated reduction in acute spend.

3. Define a consistent offer for the local population, with packages of care and clear eligibility criteria

A consistent local offer, created in consultation with decision makers, frontline staff and residents, will align everyone under a common vision and make it easier to assess impact and return on investment over time. The offer could promote integration between acute, community and mental health care, and include clear referral criteria, benchmark activity rates for each service, as well as KPIs around health outcomes, patient experience and the reduction of health inequalities.

A model for the expected impact and return on investment should be developed alongside this offer. This would allow each local system to understand the benefits of the approach and where savings should fall. Showcasing this intended impact will help create buy in from stakeholders across the system. It also provides a basis to monitor against once implemented.

4. Tackle productivity

To realise gains, it’s likely that improvements to capabilities may be required. This might include standardising staffing levels and ways of working across community services, so that the offer and care is more aligned and consistent. Initiatives can be identified that release capacity and resource within community providers to reallocate resource against gaps in service delivery. Facilitating collaboration between providers so that these initiatives are shared, and the methodology for quantifying how resources are released are co-agreed, can enable community resources to go further.

5. Collect and analyse data, measure, and refine

There is also a need to ensure that service and performance data is captured systematically, and is fully complete when it is captured, to benchmark productivity and drive improvements over time. Given that we know that community care can reduce the need for hospital care, it’s important to measure what impact the new offer is having on occupied bed days in hospitals. Improvements to community data would support this – see our article How improved community data can support NHS efficiency for our view on how this can be achieved.

About the authors

Sarah Mansuralli is Chief Strategy and Population Health Officer at NHS North Central London Integrated Care Board.

Kevin Atkin is a Partner at CF and an expert in integrated care and population health.

Bev Evans is a Partner at CF and leader of the CF finance practice.

Olivia Goodwin is Manager at CF.

We would like to thank the North Central London Integrated Care Board team for their extensive contribution to this article.

Learn more about our team.