The Value in Health series from CF explores how the NHS can improve value by delivering better outcomes with the resources available. Drawing on in-depth data analysis, the series aims to understand the relationship between cost, care, and clinical outcomes, and to identify where better resource allocation and service design could, over time, reduce pressure across the system.

Prevention has long been championed as a priority for both the NHS and government, yet in practice it remains an underdeveloped part of the health system. Whilst medicines face a triple assessment via MHRA (for safety, quality, and effectiveness), NICE (for cost effectiveness) and the NHSE (for budget impact and contracting), spending on most areas of intervention poorly tracked, and the impact of prevention programmes is rarely measured through a return-on-investment (ROI) lens.

This creates a paradox: the government has put prevention at the core of its strategy for healthcare, but there is a persistent narrative within government and the NHS that potential savings from prevention are not “cashable” by the NHS. A lack of evidence is typically cited. Ironically, the main concern expressed in the literature on economic impact of prevention is the reverse: that the main opportunities captured and quantified are ONLY from the acute sector and the significant reduced carer burden (e.g., dementia), increased productivity (e.g., mental health), and reduced criminal justice (e.g., substance misuse) are ignored despite being substantial.

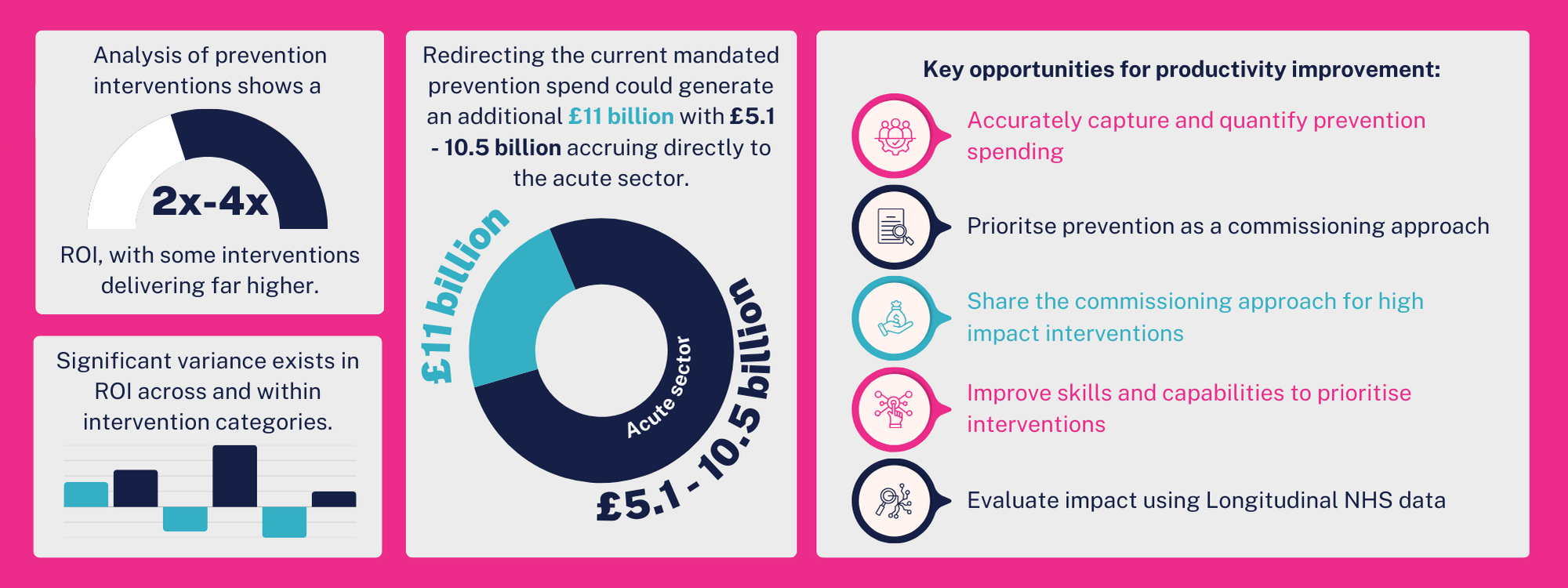

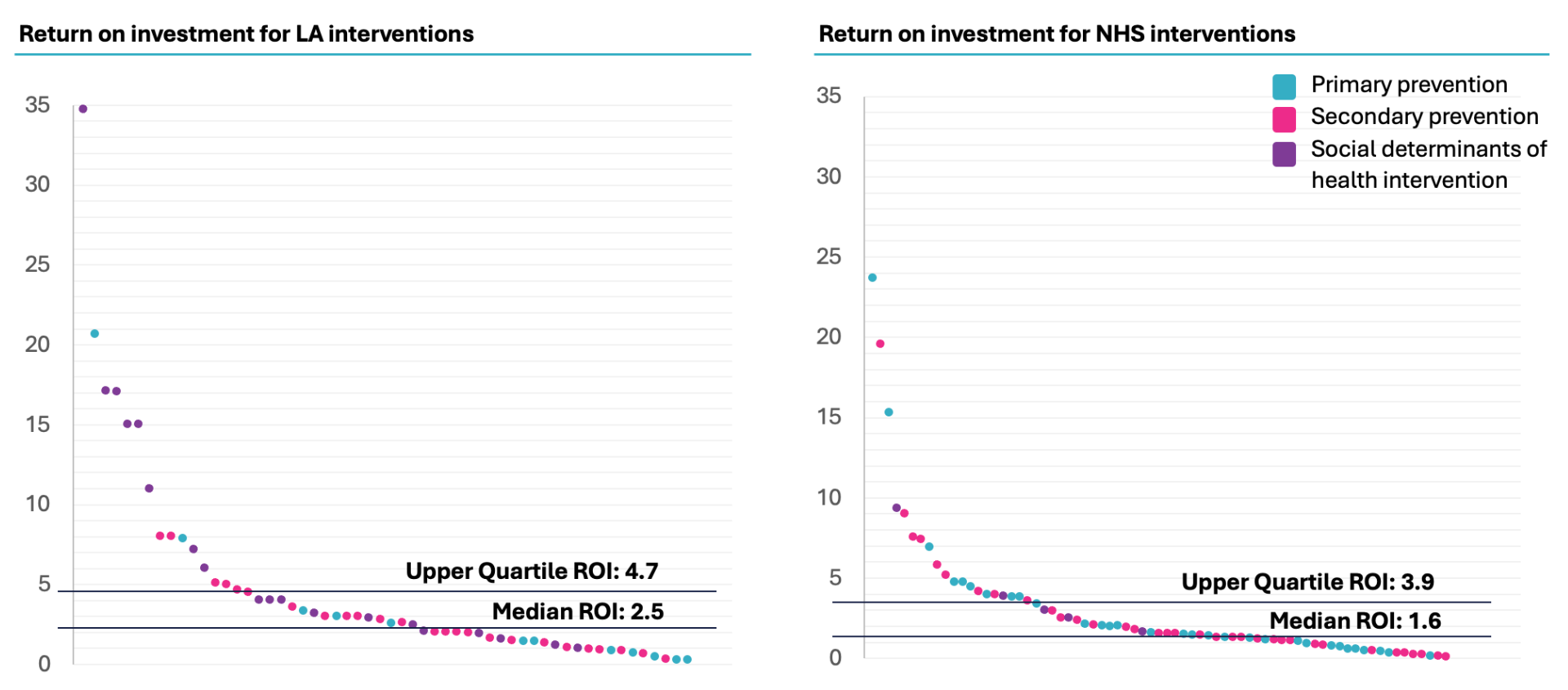

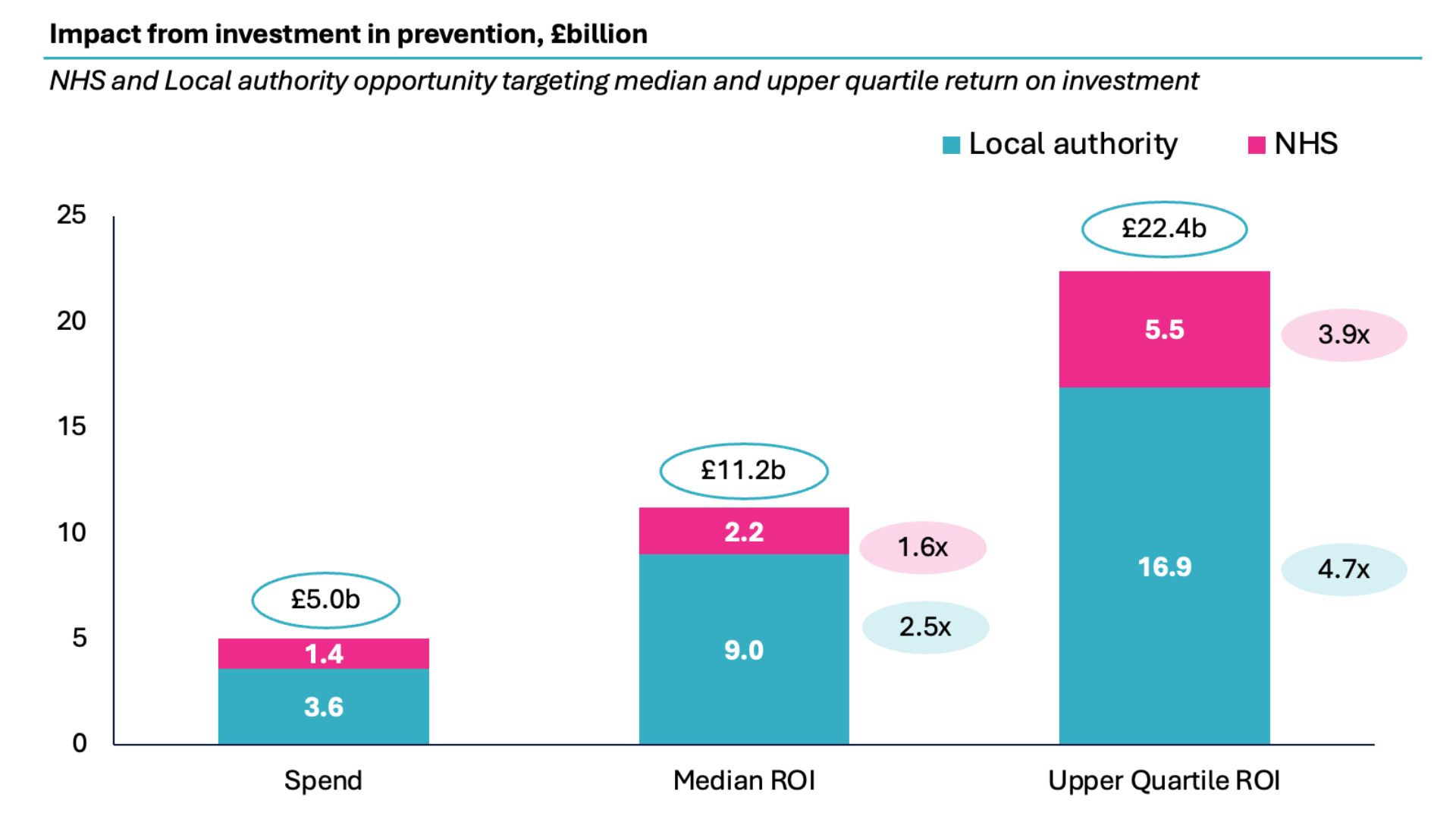

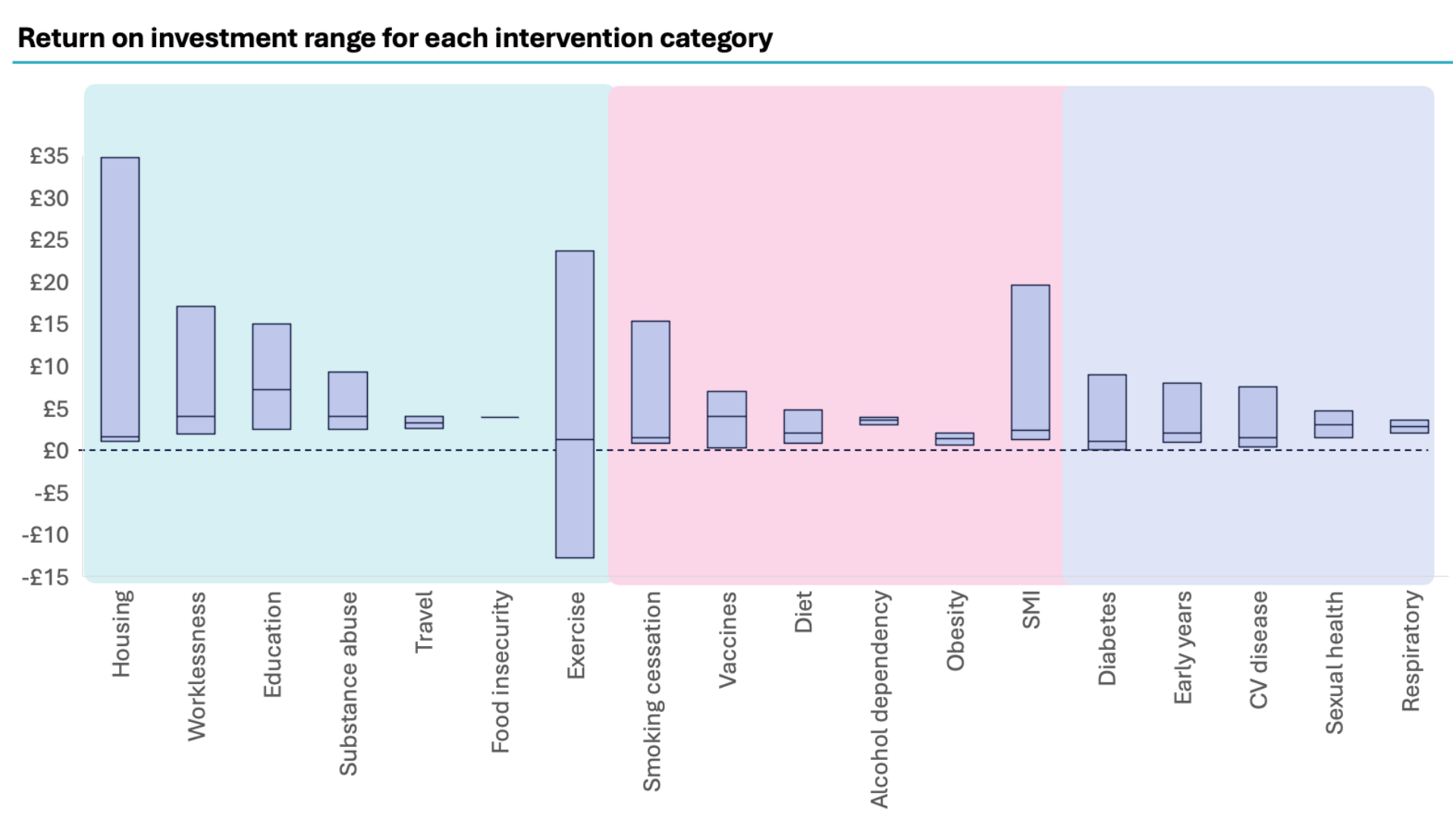

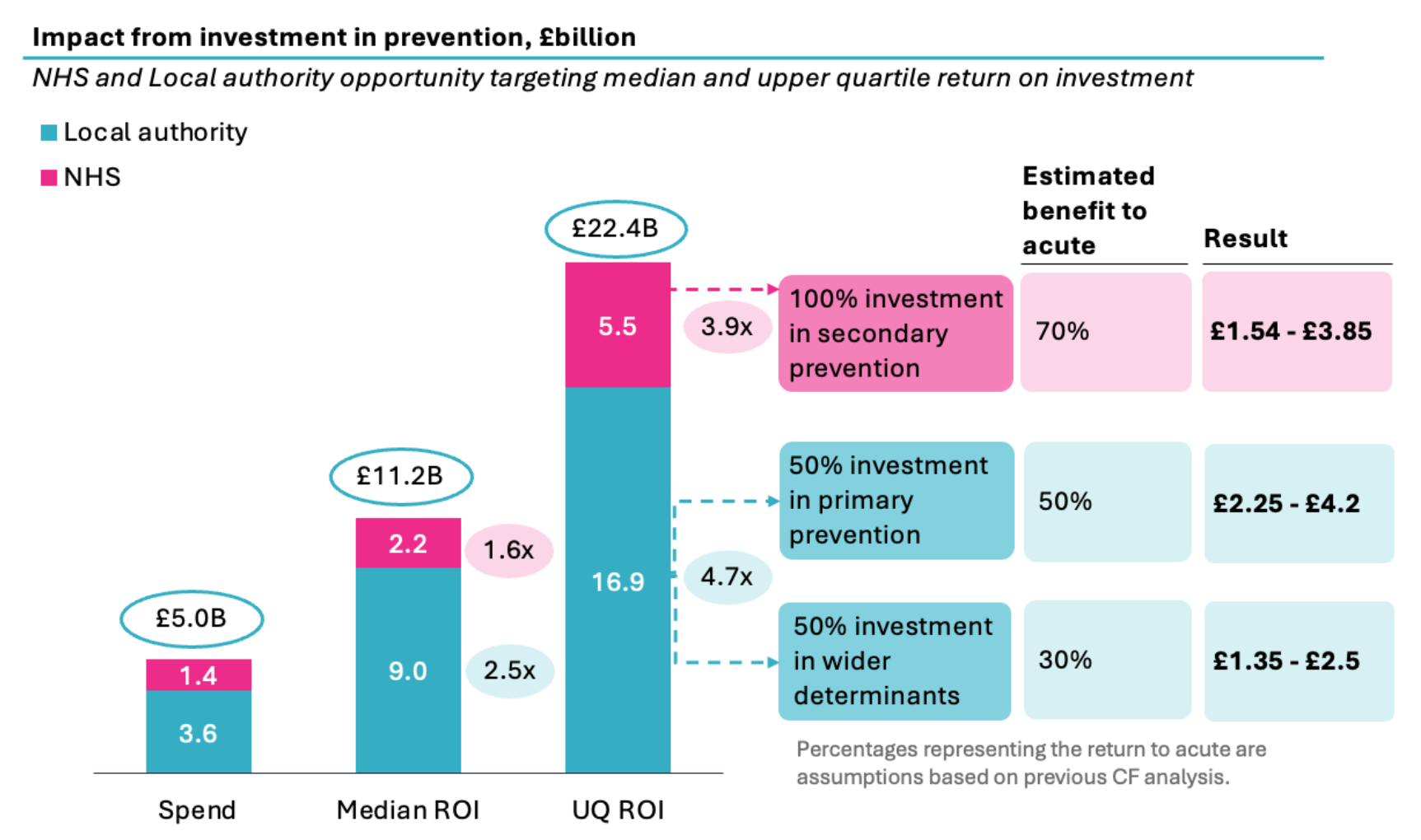

We have previously published with NHS Confederation that the ROI from prevention interventions varies enormously—from less than zero to 34 times the investment. The median return from prevention is ±2x and the upper quartile is ±4x, which suggests that better decision making about prevention could raise the return even without any increase in funding. Redirecting the estimated current £5 billion in prevention spend to reduce low-performing to increase high-performing interventions could generate an additional £11 billion in value.

Our latest analysis reveals just how large the untapped opportunity is for reducing acute spending. By mapping the nature of interventions to areas of potential impact, we estimate that between £5.1 – £10.5 billion could accrue directly to the acute sector.

This opportunity is too significant to ignore. Maximising it will require systematic use of ROI in commissioning decisions, targeted investment in high-performing interventions, and the use of NHS data, digital tools, and AI to improve targeting and evaluation.

In the final part of this Value in Health series we explore why prevention should no longer be treated as a desirable but discretionary add-on, but as a core, evidence-based investment in health and value.

What we’ve done – and why

In this latest report, we set out to deepen our understanding of the value generated by prevention programmes commissioned by both the NHS and local authorities, and to determine how resources could be reallocated to maximise returns without increasing overall spend. In this report we provide an overview of the ROI across various intervention categories, including housing, education, and those targeting specific conditions such as CVD and diabetes.

To ensure we had the most holistic view of interventions, a systematic literature review, grey literature review and expansive evidence review were undertaken to identify the most comprehensive database of prevention initiatives that impact on clinical and social determinants of health to generate the best ROIs through impacts on inequalities.

A full breakdown of our methodology can be found here.

Recap of key findings to date

The headline finding is that ROI in prevention is both highly variable and significantly under-optimised. Across the evidence base, median ROI is around 2x, with the upper quartile reaching 4x. Some interventions, however, deliver much higher returns—proof that the right programmes, delivered at the right scale, can be transformative. The variation exists not only between broad categories of prevention, but within them; for example, not all cardiovascular disease prevention initiatives achieve the same impact, highlighting the importance of selecting specific, evidence-backed models rather than relying on category averages.

Source: CF & NHS Confederation analysis, 2024

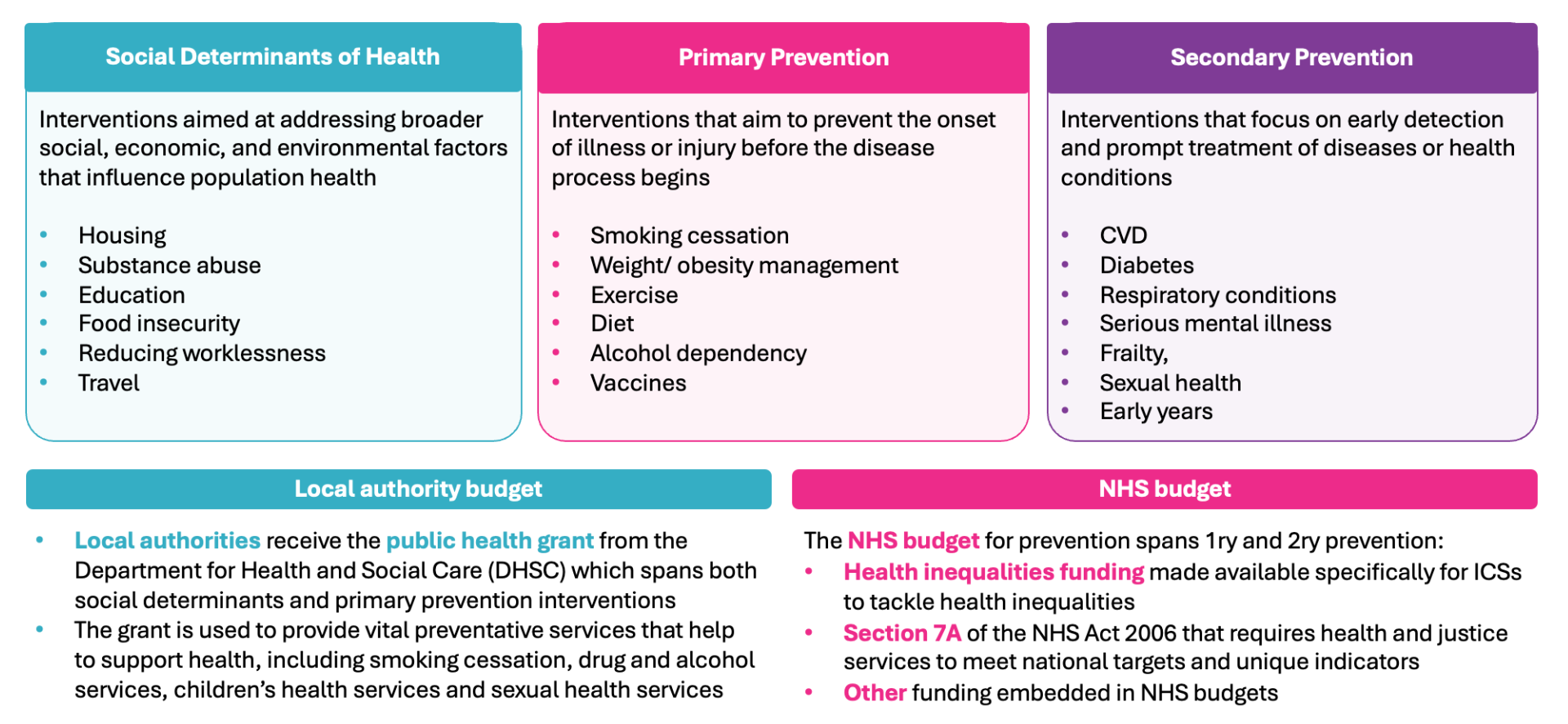

Current funding patterns reflect this split. In 2024/25, the local authority public health grant totalled £3.6 billion, with the NHS allocating £200 million to health inequalities funding for Integrated Care Systems and £1.2 billion under Section 7A of the NHS Act 2006 to meet national health and justice targets. NHS prevention spending tends to concentrate on secondary prevention, while local authorities divide their budgets between primary prevention and broader determinants. If both sectors achieved upper quartile levels of ROI, the combined value could reach £11 billion.

Source: DHSC; NHS Confederation; King’s Fund; CF Analysis

Mapping interventions to expected impact areas

The nature of the benefits also differs depending on the type of prevention:

- Social determinants (seen below in blue): Programmes addressing the social determinants of health—such as healthy diet, physical activity, housing, and employment—often deliver wider benefits to society. These can include reduced criminal justice costs, higher economic productivity, and lower welfare dependency, alongside reduced use of hospital services. Hence only 30% of the benefit is assumed to affect hospitalisation.

- Primary prevention (seen below in pink): Aims to prevent the onset of illness or injury before the disease process begins i.e. smoking cessation, weight/obesity management, diet and exercise, vaccines and alcohol dependency. Significant evidence exists about the impact on hospitalisation but wider benefits also accrue to reduced usage of other forms of healthcare and benefits to other sectors including higher productivity and economic gains. Hence 50% of benefit is assumed to accrue to hospitals.

- Secondary prevention (seen below in purple): Focuses on managing existing conditions and tends to produce savings directly within the acute sector by reducing emergency admissions for conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and substance misuse, and through interventions like falls prevention and vaccination. The evidence suggests significant focus on avoided hospitalisation as a result of better management of conditions and hence 70% of benefit is assumed to accrue to hospitals.

Source: DHSC; NHS Confederation; King’s Fund; CF Analysis

Building on these assumptions, we applied previous research on ROI from category-specific interventions to estimate the potential impact, as shown below.

Source: CF & NHS Confederation analysis, 2024

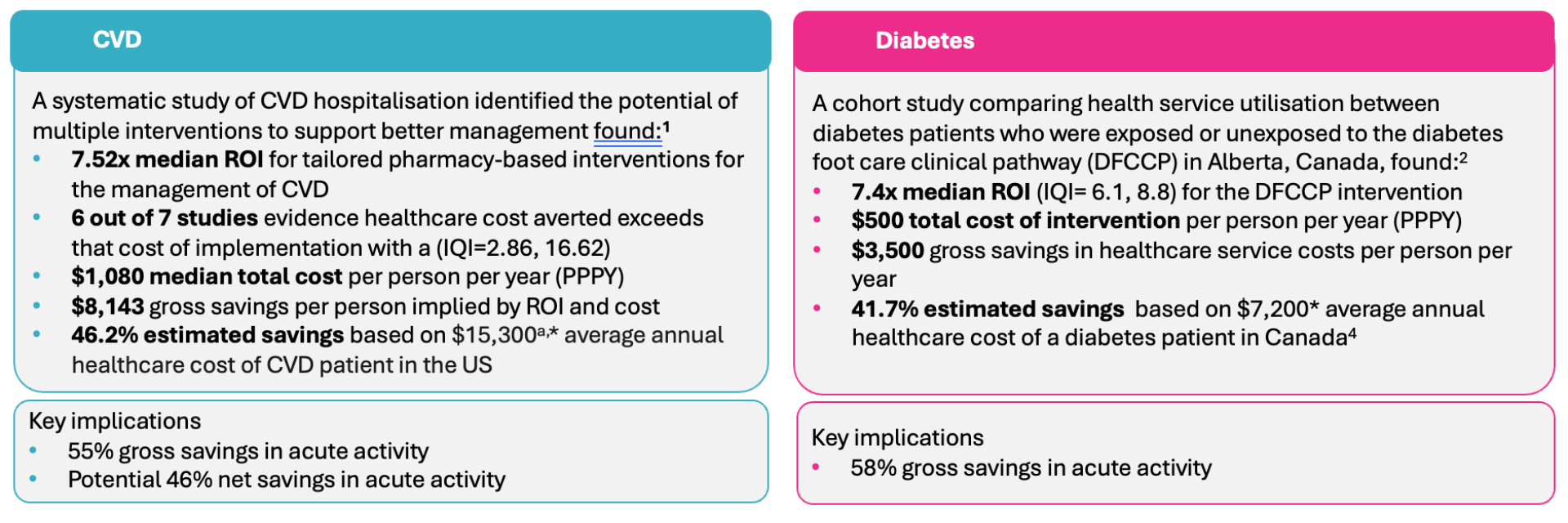

By way of illustrating what this looks like, we present examples of interventions across Europe and North America that demonstrate substantial impact. Evidence shows reductions of over 40% in annual healthcare costs per patient, while a systematic study of CVD hospitalisation identified the potential of multiple interventions to improve management.¹ Similarly, a cohort study in Alberta, Canada, comparing health service utilisation among diabetes patients exposed or unexposed to the diabetes foot care clinical pathway (DFCCP), found significant benefits.

1. Jacob, V. et al. (2022) ‘Pharmacist interventions for medication adherence: Community Guide economic reviews for cardiovascular disease’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62(3). doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2021.08.021. 2. Thanh, N.X. et al. (2020) ‘Return on investment of the Diabetes Foot Care Clinical Pathway Implementation in Alberta, Canada’, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 165, p. 108241. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108241. 3. Haidar, A. et al. (2025) ‘National costs for cardiovascular-related hospitalizations and inpatient procedures in the United States, 2016 to 2021’, The American Journal of Cardiology, 234, pp. 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2024.10.003 4. McBrien, K.A. et al. (2013) ‘Health care costs in people with diabetes and their association with glycemic control and kidney function’, Diabetes Care, 36(5), pp. 1172–1180. doi:10.2337/dc12-0862.* Adjusted for inflation.

Updating our previous analysis to take account of where the benefits fall suggests that the acute sector would receive £5.1b – £10.5b of the posited £11-22b opportunity from improved investing in prevention. We have assumed 70% of secondary intervention, 50% of primary intervention and 30% of wider determinants benefits the acute sector.

Source: DHSC; NHS Confederation; King’s Fund; CF Analysis

Engagement with key leaders indicates that the NHS prioritises secondary prevention while local authorities focus on primary prevention and social determinants of health (SDOH). Therefore, we have shown here the NHS prevention spend being targeted at secondary prevention and Local authority prevention spend being split between primary prevention and wider determinants.

Whatever the level of savings being targeted, the fact that the median ROI is 2x and upper quartile 4x, suggests it is reasonable to invest 25% to 50% of the expected savings from these initiatives in order to achieve the benefits of prevention.

Despite this, the potential remains largely unrealised. Prevention spending is not consistently recorded, ROI is rarely used as a commissioning criterion, and many commissioning bodies lack the skills and capabilities to evaluate interventions effectively. Budgetary constraints and historic allocations often lock funds into programmes with limited impact, while high-value opportunities go underfunded. Yet advances in predictive analytics, digital tools, and NHS-linked datasets now make it possible to identify high-return opportunities earlier, target interventions more precisely, and evaluate outcomes more rapidly than ever before.

Recommendations

The NHS must develop a ‘business-like’ approach to systematically identify high-value interventions and limit low-value interventions:

The NHS and local authorities already spend billions each year on prevention—but without a deliberate, evidence-based strategy, much of that spend is delivering below its potential. This approach does not necessarily require more money—just smarter investment. By taking a value-based commissioning approach and harnessing modern data tools, the NHS and local authorities can unlock billions in additional value, improve health outcomes, and deliver on the promise from sickness to prevention.

This is the final part of the Value in Health series. To read the rest of the series, follow the links below:

- Part 1: Improving productivity, quality and prevention in the NHS (full report)

- Part 2: Addressing the productivity challenge in acute care

- Part 3: Unmet care gaps in the treatment of chronic diseases

To learn more about this report or our other work surrounding value in health, contact our team today.

About CF

CF is a leading consultancy dedicated to making an enduring impact on health and healthcare. We work with leaders and frontline teams to improve health, transform healthcare, embed life science innovation and boost growth through investment. With unmatched access to UK healthcare data and award-winning data science expertise, our team are a driving force for delivering positive and meaningful change.

About the authors

Ben Richardson

Ben Richardson is a Managing Partner at CF, leading Life Sciences and Data Innovation. With two decades of experience, he has worked with health systems and life sciences companies globally, focusing on strategy, transformation, and development. Ben has contributed to primary care, diabetes, cardiovascular, cancer, mental health, and population health management. Since 2014, he has helped CF become an award-winning healthcare company in management consulting and data services.

Yemi Oviosu

Yemi is a Senior Manager at CF with a PhD in Cardiovascular Biochemistry, specialising in strategy and scaling innovation for healthcare and life sciences clients. He focuses on evaluating and implementing digital technologies that enable population health management and driving sustainable, enterprise-wide transformation. His unique blend of scientific insight and technology-strategy expertise helps clients accelerate innovation, de-risk investments, and improve patient outcomes.

With special thanks to Catherine Skilton, Jo Andrews, Sophie Lee, Beena Mistry, Colette Russell, Dike Aduluso, Sarah Sharer, Martin Shiderov, Lali Sindi and Gauri Patel.

Note: This report was partially funded by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI), no editorial input was provided.