What we cover in this article:

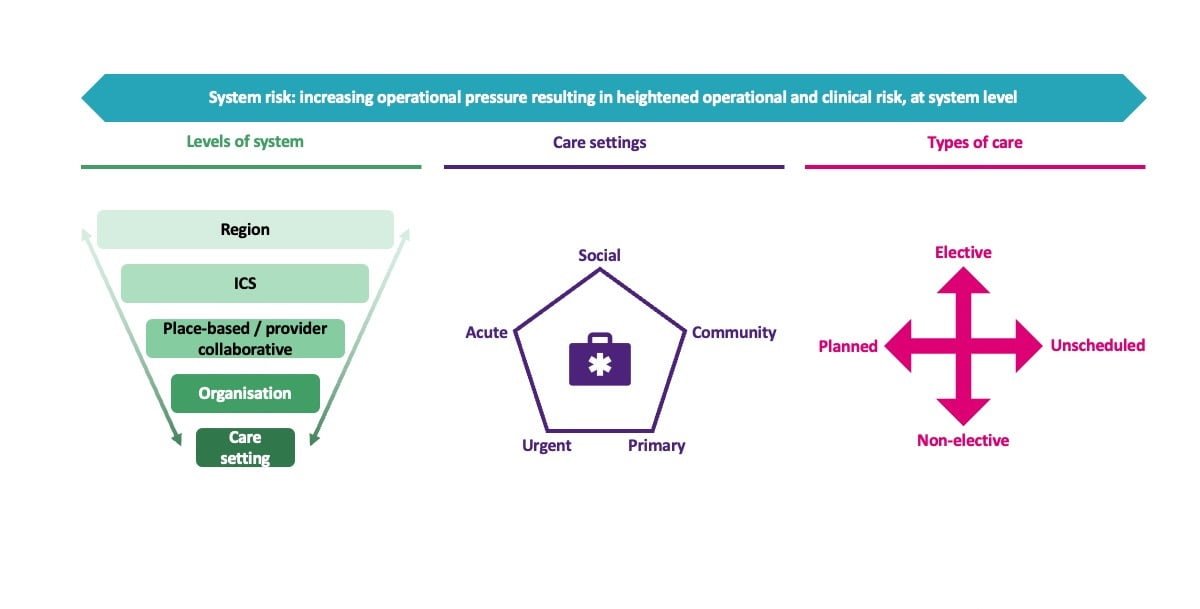

- We define system risk as increasing operational pressure resulting in heightened operational and clinical risk, at system level – we break down what this means for NHS partners and how system risk can be better managed

- We explain why, when starting on the journey of improving your system risk approach, it is important to develop some underpinning principles to guide stakeholders on this journey and create common thinking for the system

- We unpack how risk across the system can be made visible for decision makers to enable more informed and therefore better decision making

- We outline how senior decision makers may best be supported to articulate risk to each other, to help guide them when what they are planning to do may impact on the system as a whole

What is system risk?

The Oxford dictionary defines risk as “A measure of the likelihood or probability that damage to life, health, property, and/or the environment will occur as a result of a particular hazard”.

Within the healthcare context, the word risk can have many immediate connotations in our minds – governance, care delivery, regulations and can be applied at system, organisation and individual level and has different implications in different contexts.

Using a systems thinking approach across the NHS, we need to be able to consider risk conceptually and disect it in a manner which enables providers and professionals collectively and individually to feel autonomy for understanding and managing risk across the system.

In our work with ICS systems, we’ve reflected with senior clinical and operational leaders to define what system risk is to them. Put simply, we collectively defined it as: increasing operational pressure resulting in heightened operational and clinical risk, at system level.

Let’s break this down further, starting with “system”. In reality, the system connotation here means that we need to consider firstly what this means for an ICS and/or group of place-based partnerships. How do organisational, place or care setting operational pressures combine and escalate to the status of the system? It also means we need to consider which pressures and risks would benefit from system level responses and thinking.

As we draw our attention on to “risk”, this is about what those pressures mean for the system’s ability to deliver care, and how the system can best balance those risks both at any specific location and across the system (place to place, provider to provider or care setting to care setting). The aim is to ensure that the majority of service users receive the best care that can be delivered in totality across the system, regardless of place, provider or care setting, and considerate of the pressures faced. Risk must also be balanced across different types of care: unscheduled and planned; elective and non-elective; and, health care and social care.

System risk encompasses considerations at many levels, for instance:

There are some constraints of how and the extent to which system risk can be addressed. These include acknowledging that there will always be external factors (such as funding and workforce), and that whilst improvements to business as usual (BAU) will have a po2sitive overall impact on a system, these improvements will not explictly identify and directly tackle system risk. It is also important to acknowledge the existence of harm, as effectively managing system risk becomes increasingly crucial in situations where the healthcare system is under substantial pressure, as doing the greatest good for the greatest number is also about doing the least harm to the most people when harm may not be avoidable.

Agreeing a set of principles is fundamental to guiding a system’s risk approach

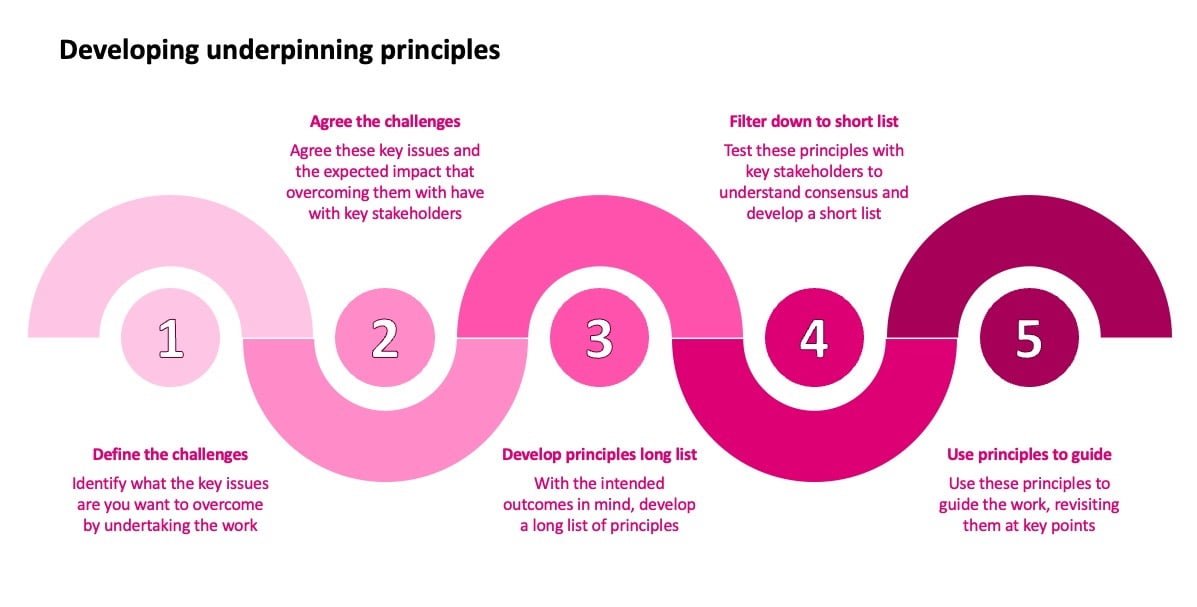

As our conceptualisation of system risk so far has shown, this can be a tricky topic which may feel somewhat abstract and difficult to make tangible in reality. For this reason, when starting on the journey of strenthening your system risk approach, it is important to develop some underpinning principles to guide stakeholders on this journey and create common thinking for the system.

These principles could cover multiple themes, such as the greatest good for the greatest number, harm reduction, equitability, visbility, and clarity – to name a few.

Within this development process, it is important to remain mindful of considering vulnerable groups and inequalities. It may need to be acknowledged that accepting greater system risk may impact on the personal risk of practitioners, and that this should all be executed through open, honest and trusted behaviour focused on people – staff, patients and the population.

A high level process for creating a set of principles is illustrated here:

To better manage system risk, it must first be seen and understood

Healthcare professionals, managers and clinicians, make difficult decisions all the time about patient care balancing a plethora of different factors, including the risks to a patient and others if a certain course of action is or isn’t taken.

Whilst these professionals may be skilled decision makers, their abilities to make these judgements are limited by the situations, risks and consequences they can see directly before them – whether that be the individual patient a clinician is treating, or an entire hospital a manager is leading. They cannot make decisions which factor in considerations which they cannot see and of which they are not aware.

For this reason, risk across the system must be made visible for decision makers to enable more informed and therefore better decision making.

Let’s think about the importance of understanding system risk this across three levels

First, individual clinicians are continuously balancing risk to make the decisions which are clinically best for the individual patients in front of them – however, they are unaware of how those decisions may inadvertently impact on risk for patients elsewhere.

Second, individual organisations providing care are continuously balancing risk within their care settings to make the decisions which are clinically best for the collective cohort of patients for which they are responsible – however, they may be unaware of how those decisions may inadvertently impact on risk for patients being cared for in other organisations within an ICS.

Third, as an ICS develops it can leverage opportunities to create more connected care through collaboration, centred on the best outcomes for the entire population which it serves – having an agreed system risk approach would enable individuals and organisations to make better decisions for all patients, rather than only being able to see the impacts on the patients for whom they are directly providing care at any one time.

Making system risk visible has multiple potential benefits, for example: the ability to clearly articulate where risk is being held in the system; making collective understanding of risk more objective; an improved comprehension of the relationship between pressure and risk; and, allowing decision makers to compare potential scenarios more easily before taking action.

In practice, risk could be visualised in many different ways

When creating any form of information sheet, dashboard or tool, it is important to keep the purpose, the intended outcome, and the intended user at the centre of what is developed. As a starting point, three prompt questions can be helpful.

First, consider the inputs, what information do you need, what do you want to measure, or to which data do you want access to allow senior decision makers to better understand current system risk levels?

Second, consider the processes, how will you synthesise this information in a way which meets the purpose of the tool – in whatever form it may be – whilst ensuring the volume of information is not overwhelming?

Third, consider the outputs, how will the finished tool – in whatever form it may be – best enable the outcome of system risk being made as visible as possible in a way which enables decision makers?

There are several elements which can be used to characterise what is visualised, for example:

- Will patient safety be represented in terms of mortality or morbidity?

- What importance should patient and staff experience have in this work?

- What levels of the system and what care settings should be considered?

- Should any elements be weighted with greater significance than others?

We worked with an ICS to help them collectively define system risk in their context and determine how to manage it better in practice

The joint-SRO for the system risk work (who is also a medical leader) told us:

“Thank you for helping us challenge ourselves and each other in a supportive way, we have moved our collective understanding on considerably. You were able to keep the pace of this work moving, as we needed it, whilst allowing us time to hear everyone involved. Your summary of many hours of work, has helped us share the output widely and continue to progress.”

Articulating what risk looks like in reality can help system partners understand how best to support each other

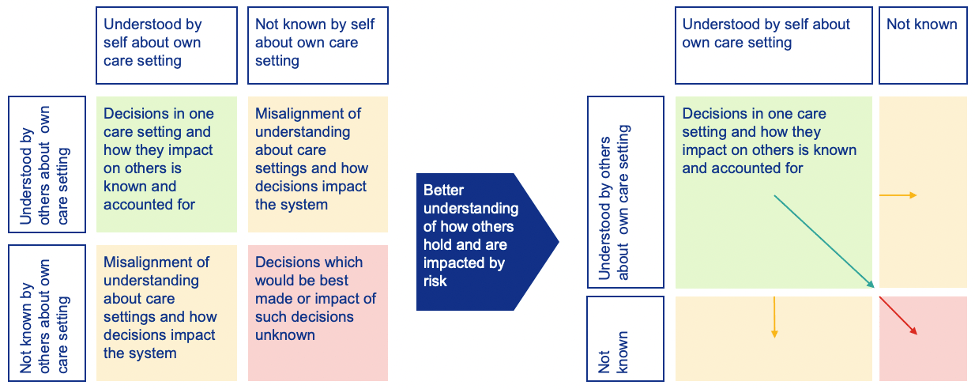

Decision makers in one care setting can have a lack of understanding and appreciation of the intricacies of how other cares settings hold risk in the way they work, which can lead to decisions being made in one setting without a holistic understanding of the impact this may have on other care providers. In terms of greatest operational pressure, this may lead to an increased likelihood of harm occurring in the system.

The impact on system partners of better understanding how others hold and are impacted by risk is demonstrated in this illustration:

It is important to therefore consider how senior decision makers may best be supported to articulate risk to each other, to help guide them when what they are planning to do may impact on the system as a whole.

This could take place in many forms, for example we supported one client to create a risk articulation framework document for each care setting in their system, working with a range of stakeholders to explore and explain what operational pressure and clinical risk looks like to them, and what that care setting and their system partners needed to be most considerate of when making decisions which would impact on the system.

It is often the act of bring a breadth of stakeholders together to complete such exrcises which brings the most value. Ultimately, conversation is the starting point for building shared understanding and – eventually – positive collective change.

Interested in better understanding and responding to operational pressure?

Read our operational effectiveness expert report, “Optimising OPEL frameworks to drive system wide operational improvement”, available on our website.

To learn more about our operational effectiveness work, contact our Partner, Tessa Walton, for a virtual coffee or an in-person conversation.