This report was commissioned and funded by AbbVie.

Summary

The NHS is currently facing unprecedented demand in the aftermath of COVID. The pandemic saw many patients unable to access the care they needed. As a result, we are now seeing a growing demand for NHS services as patients who were not seen during the pandemic return for diagnosis and treatment. One service under significant pressure is Dermatology, which currently has over 380,000 people waiting longer than 18 weeks and, as this report shows, a backlog from the pandemic that could take many years to clear.

To help tackle this challenge, new policy and practices are emerging outlining innovative digital solutions to improve capacity along the dermatology pathway, including the use of Teledermatology for triage, pathway optimisation, and patient self-management.

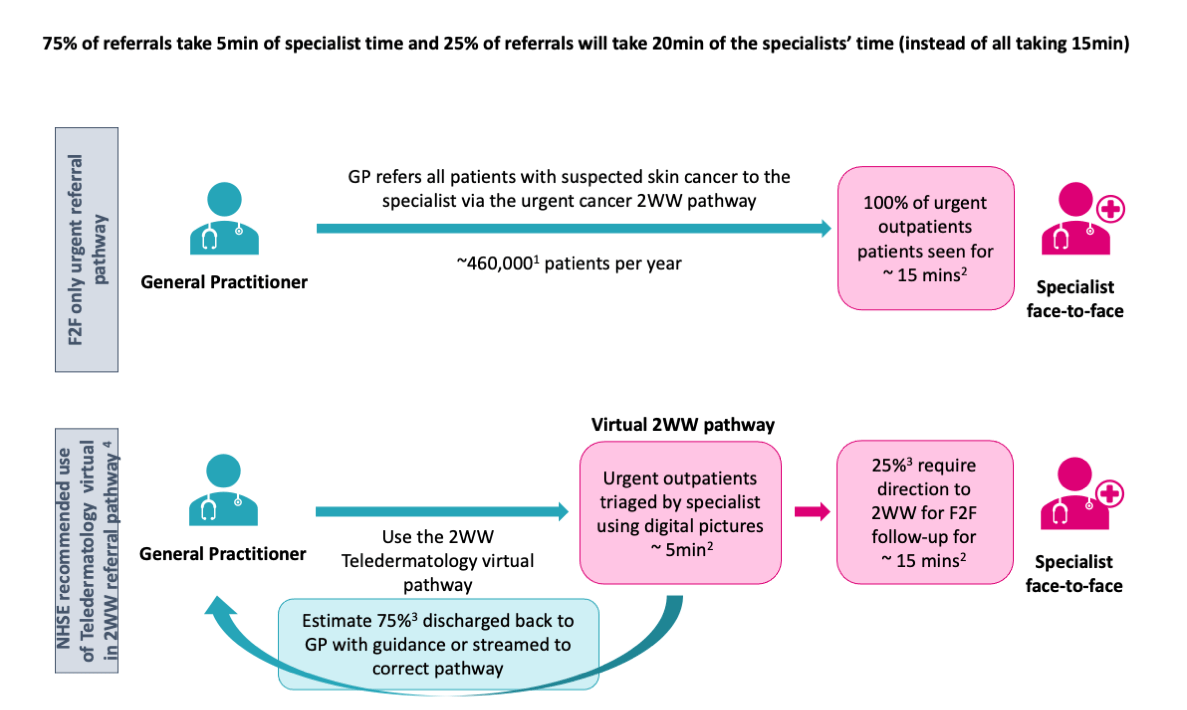

One new specific policy with potential to significantly save NHS system capacity is the Teledermatology virtual urgent skin cancer two week wait (2WW) pathway. Each year, approximately 460,000 patients are referred through the 2WW face-to-face referral pathway for GP-suspected skin cancers. However, only around 6% of referrals lead to a diagnosis of melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma cancers.

CF have developed a report which shows that applying this agreed model of Teledermatology to the urgent 2WW skin cancer referral pathway might create significant capacity in the service and contribute towards reducing NHS backlogs.

To explore the potential for this policy change CF have developed a report which shows that applying this new virtual 2WW model of Teledermatology, using high quality images – including dermoscopic images – to help ensure face-to-face hospital attendance only when necessary, could, if widely adopted, create significant capacity in the service that potentially could be redeployed to other dermatological conditions, e.g. inflammatory skin conditions and contribute towards reducing NHS backlogs.

There is huge demand for dermatology, and limited clinical capacity

There is huge demand for NHS dermatology services. One in four (13.2m) people in England and Wales see their GP about a skin, nail or hair condition every year.[1] There were 3 million dermatology outpatient appointments in England in 2019-2020, making it the sixth highest treatment function in terms of volume.[2] Dermatology services receive more urgent referrals for suspected cancer than any other specialty and NHS dermatology units carry out around 200,000 procedures to surgically remove suspicious and malignant skin lesions every year.[2]

Current dermatology workforce capacity struggles to meet this vast and growing demand. Latest reports show that almost a quarter (159) of the required 659 Whole Time Equivalent (WTE) consultant dermatologist posts in the NHS in England are unfilled.1 In this constrained staffing environment, urgent demand from suspected cancers is prioritised which leads to limited clinic-slots and delayed outpatient appointments, and an inequity of care for patients with inflammatory skin conditions like eczema, psoriasis, and acne.[3] Leaving these long-term conditions for months or years without treatment could mean these diseases progress and may cause increased pain, psychological issues and sometimes disability.

COVID-19 destabilised the service, creating a vast backlog of cases

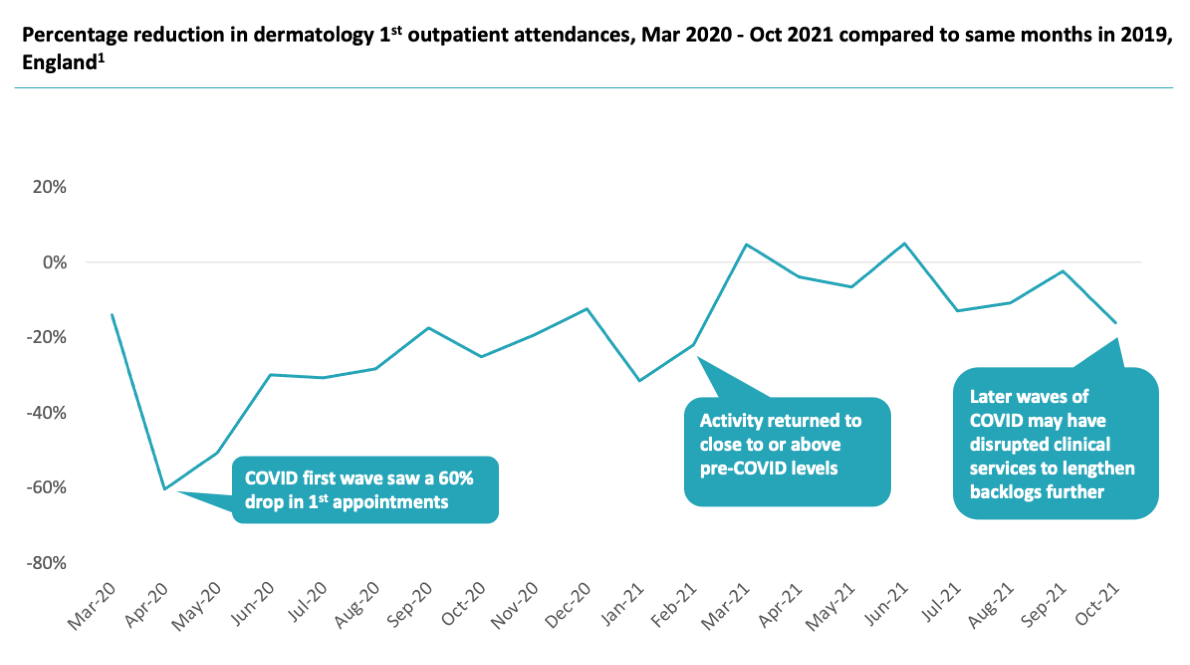

Covid-19 heavily exacerbated this gap between dermatology demand and supply of specialist care. During the first year of the pandemic (Mar 2020 to Feb 2021) approximately 300,000 of the expected first outpatients’ appointments in dermatology did not take place – in effect they were ‘missing’ – compared to the same period in the year before. It follows that there may be a number of people who were left undiagnosed and living with untreated, potentially severe inflammatory skin conditions. Overall, there is evidence of a possible ‘backlog’ of almost a million dermatology outpatient appointments missing from the available data during the period March 2020 to October 2021.[4] [5]

Figure 1: Change in dermatology outpatient attendances between March 2020 and October 2021 compared to the same months in 2019/20[6]

Our analysis shows that for specialists to see these people and clear the backlog within a year would take an immediate – and practically impossible – 30 percent increase in NHS dermatology capacity over and above filling any current specialist vacancies. Clearly, to stand any chance of even approaching this goal, significant investment and changes will be required. Incremental change or ‘more of the same’ will not begin to address the problem. For example, even an aggressive 10 percent capacity increase would perpetuate the backlog for almost 4 years.

The right Teledermatology model provides part of the answer

Digital capabilities may provide some of the answer. Telemedicine is often quoted as being a potential arrow in this quiver. The shift to digital services – including Telemedicine where appropriate – is a central tenet of the NHS’s future direction and current guidance.[7] In dermatology, dermatology telemedicine – often called Teledermatology – has suffered from confusing definitions and inconclusive efficacy in the past[8] which may have contributed to low levels of uptake to date. In response to a questionnaire by GIRFT[9] to 117 NHS Trusts, 30% reported that their local Teledermatology services are adequately and safely integrated with their services. 52% said their local Teledermatology services are not adequately and safely integrated with their services. 18% had no local Teledermatology service at all.[1]

However, NHSE’s Outpatient and Recovery Transformation Programme (previously named National Outpatient Transformation Programme) together with other stakeholders including the professional association – the British Association of Dermatologists – have clarified defined pathways and use cases where Teledermatology can begin to create significant value for patients and clinicians. A critical example among these is the new 2WW cancer pathway, which proposes the use of a Teledermatology virtual pathway, where high quality images accompany the 2WW dermatology referral to help ensure face-to-face hospital attendance only when necessary. [2],[10]

The speed and efficiency of this model has the potential to reduce the overall dermatology workload and free up specialist time to treat the significant numbers of patients waiting for treatment, in particular the high number of patients with undiagnosed or undermanaged inflammatory skin conditions.

In this report we show that applying this agreed model of Teledermatology to the urgent 2WW skin cancer referral pathway might create significant capacity in the service and could have a demonstrable benefit on NHS backlogs.

Figure 2: Modelled impact of Teledermatology virtual pathway on the 2WW referral pathway in terms of consultation time and triage effectiveness [10],[11],[12],[13]

For good reasons, suspected skin cancer is prioritised within dermatology services and takes up a significant portion of clinical activity. Each year, around 460,000 patients are referred to the face-to-face cancer urgent referral program. We estimate that initial review of these patients takes 115,000 hours of specialist clinical time. Of these patients, only around 6% are diagnosed with melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma cancers9, many of which can be positively identified (or ruled out) from a set of dermoscopic images in the new virtual 2WW Teledermatology model.

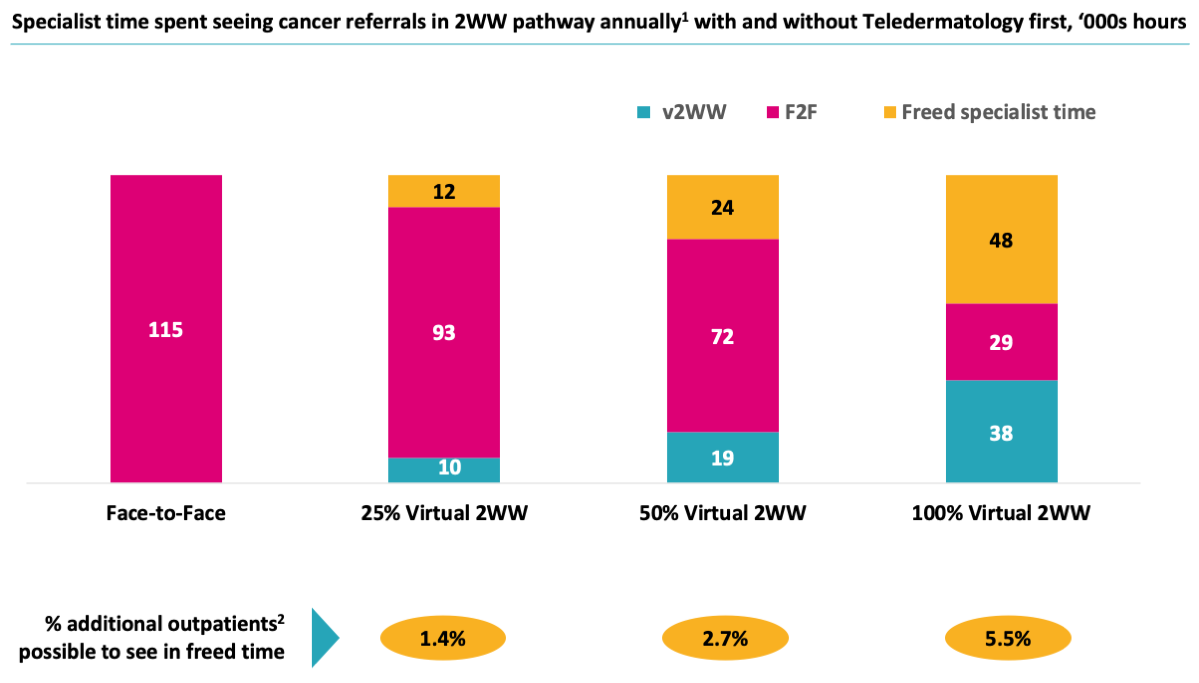

We identified savings of up to 48,000 hours of specialist time if this Teledermatology model was adopted as the standard form of assessment for 100% of urgent cancer referral patients instead of a traditional face-to-face 2WW model. In this model, only 29,000 hours – 25% of the previous total – would be spent in face-to-face clinic seeing urgent cancer referrals whose images require further review. In practice, this means that the cancer patients are still seen urgently but that this demand management creates over 5% extra specialist capacity across the specialty. These freed-up specialists could then potentially begin to do the work of reducing the backlog of patients who often need urgent diagnosis or management of debilitating inflammatory skin conditions.[14]

Figure 3: Specialist time spent seeing cancer referrals in 2WW pathway annually with and without Teledermatology triaging, ‘000s hours [15], [16]

This equates to a WTE requirement of approximately 24 WTE specialists’ time, or equivalent to almost 15% of the unfilled WTE consultant posts.

This of course is only part of the story; the use of Teledermatology has wider pathway applications to create additional capacity and transform dermatology services, as detailed in the most recent NHSE Referral Optimisation for People with Skin Conditions guidance, issued in September.[3]

To have an impact, unified, population-level adoption is required

However, achieving this impact does require a system-wide change to have population-level impact, either at ICS or national level.

Of course, this new approach – like any new way of doing things – will require several limitations, risks and hurdles to be overcome. Communication and direct engagement with patients, e.g., for face-to-face reassurance, is harder, determining the reimbursement model will take some work, and clinical efficacy will also need to be under constant study and review. It will also be critical to ensure systems have the equipment needed to take and send the required good quality images. The technology will need to be developed to the point that this becomes easily adopted as a user-friendly experience, with low upfront investment for both primary and secondary care.

Finally, given the ambition and significant potential of Teledermatology, we have highlighted several enablers of the path forward:

- National leadership and shared goals will be required to enable a common direction and ongoing accountability.

- Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) will need to be monitored and supported to implement these pathways.

- Clear funding requirements need to be determined and common technology applications developed to support trust level roll out.

- The technology standards will need to meet the ambition of the programme and primary care need to be provided with the necessary equipment and people to take and send the required good quality images.

- Clinical pathways will need to be standardised, monitored, and studied to ensure quality standards are upheld.

- The new redesigned dermatology pathway will need to be embedded in practice through training and enabling staff, in both primary and secondary care and support given to patients to understand the process.

See the full report for the methodology and further details.

References:

[1] GIRFT Dermatology, Programme National Special Report: https://www.gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Dermatology-overview.pdf

[2] A Teledermatology roadmap 2020-21, https://www.imperial.nhs.uk/~/media/website/services/dermatology/gp-referral/notp-Teledermatology-roadmap-202021-v10-final.pdf?la=en (Accessed August 2022)

[3] NHSE Referral optimisation for people with skin conditions, September 2022, https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/B1149-referral-optimisation-for-people-with-skin-conditions.pdf (Accessed September 2022)

[4] CF analysis of NHS HES data. Further Covid impact is likely to have increased this backlog. The number of those waiting for treatment from before the pandemic or the ability for the system to cope with demand in steady state has not been factored in. These factors may contribute to a worse picture.

[5] The continued effects of COVID beyond October 2021 including the Omicron variant surge are likely to have exacerbated the situation further since this work was concluded. An indication of this can be seen in the national dermatology service referral to treatment times (RTT), which in October 2021 showed 70% of patients were started on treatment within an 18-weeks of referral. In March 2022 (post main omicron wave) this number stood at 63%, in August 2022 (latest available data in November 2022) this number was 64%.

[6] CF Analysis of HES Outpatient and APC data, England, Mar 19 – Nov 21. CF analysis ‘First’ outpatient attendances are those flagged as the initial visit for a particular condition, as opposed to a subsequent/follow-up attendance

[7] https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/20211223-B1160-2022-23-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance-v3.2.pdf

[8] Dermatology Digital Playbook NHSX: https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/key-tools-and-info/digital-playbooks/dermatology-digital-playbook/dermatology-pathway/

[9] NHS Get it Right First Time (GIRFT) Report, August 2021

[10] NHSE and British Association of Dermatologists, The two-week wait skin cancer pathway, April 2022

[11] CF analysis. 460,000. eRS 2WW Skin data, whole year Jan-Dec 2020

[12] Conservative estimate of time for F2F and A&G specialist review based expert view and NHSX Dermatology Digital Playbook, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust.

[13] NHS expert interviews for reasonable general applicability. 75% a conservative estimate of the 94% cited as being non-malignant at secondary care consultation to include benign lesions.

[14] Model is based on a hypothesis and uses best practice case studies. See assumptions described in the report document. 2WW skin cancer referral data runs to Oct 21, data available at time of analysis (Feb 22).

[15] CF analysis. 460,000. eRS 2WW Skin data, whole year Jan-Dec 2020 2WW Face to face takes 15min, A&G takes 5min.

[16] Over 2020 annual non2WW face to face pre COVID outpatient appointments Feb 2019-Jan 2020 3.55M appointments, HES