The promise of life sciences innovation is exciting. Disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s, effective obesity drugs, increasingly individualised precision medicines, cancer immunotherapy and vaccines, and advanced therapies and platform technologies like cell and gene therapies are emerging at an exponential pace. These combined with advances in early patient identification such as low cost, non-invasive liquid biopsies for cancer and dementia, are creating extraordinary opportunities to transform healthcare and improve patient outcomes across a range of diseases.

While this transformative potential is at the core of the UK government life sciences strategy, this sector faces some particular challenges. As a truly global industry, the “market” for life science research and jobs is subject to intense international competition. The success of the NHS in flexing its bargaining power means good deals for the NHS translate into some of the lowest net prices and margins in the OECD. Uptake of innovative new therapies has historically been slower and more variable compared to other countries. This places a dampener on the enthusiasm of the life sciences industry for the UK market.

Indeed, a survey and series of interviews with life science industry leaders revealed that some of the most common challenges have to do with variable local clinical leadership, a lack of timely and integrated guidance for whole pathways, slow and variable local formulary decisions, and multiple layers of bureaucracy to navigate.

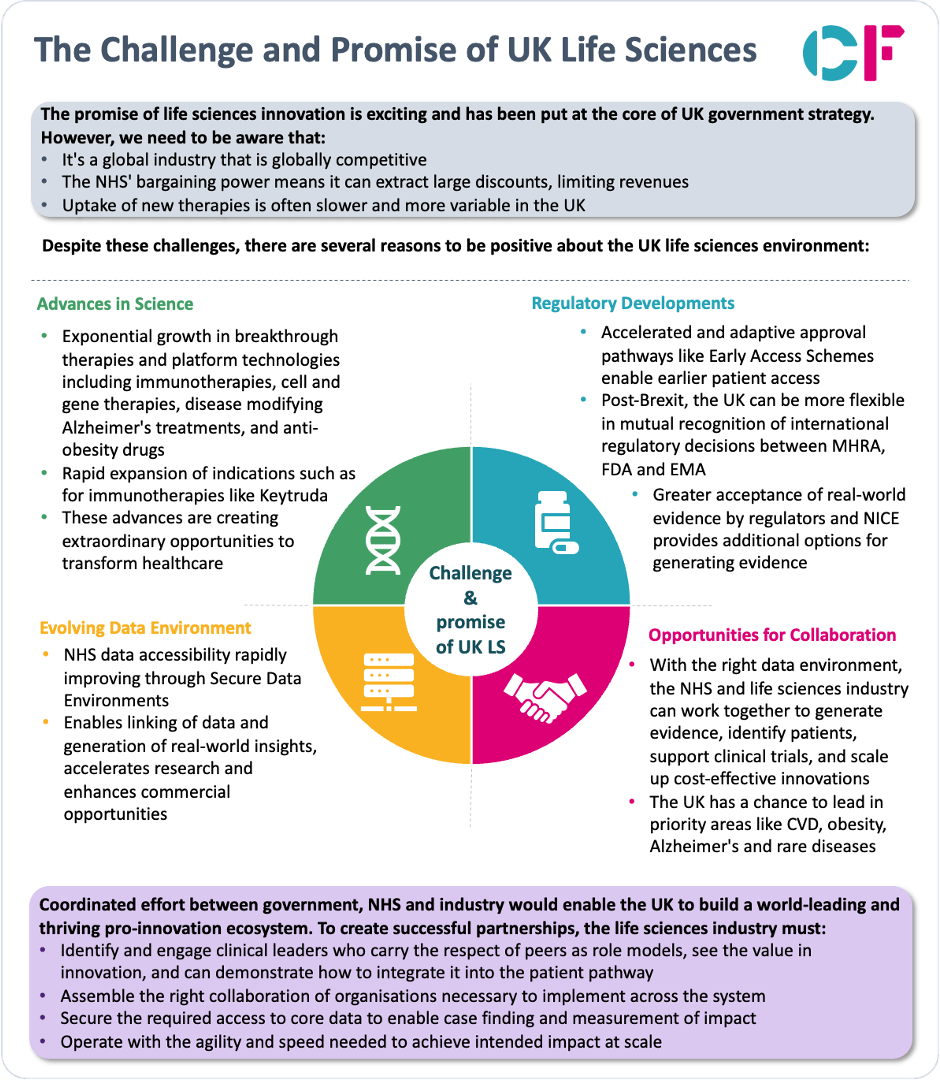

Despite these hurdles, there are several compelling reasons for the UK life sciences sector to be optimistic right now, including 1) advances in science, 2) changes in regulation, 3) data developments, and 4) opportunities to collaborate. Combined they hold the potential that could make the UK the best place to research, develop and use new medicines, and with it open up potential for greater economic activity in local areas that embrace this.

Click to enlarge

1) Advances in Science Creating New Possibilities

The rapid growth in breakthrough therapies is opening up possibilities that did not exist just a few years ago. On one hand, there has been an explosion in potentially curative therapies like cell and gene therapies, with over 1,000 regenerative medicine trials underway globally in 2022. On the other hand, there has been an exponential growth in the number of indications being evaluated for existing therapies. For example, Merck’s blockbuster cancer immunotherapy Keytruda is now approved for over 30 cancer types. In neurodegenerative disease, new disease-modifying Alzheimer’s therapies are bringing hope of significantly slowing cognitive decline. Obesity is being targeted by promising new drugs like semaglutide. And the revolution in advanced targeted therapies and platform technologies like CRISPR gene editing means treatments can be precisely tailored to a patient’s specific genetic profile.

Taken together, these global advances in innovative new modalities and rapid expansion of indications are creating extraordinary opportunities to transform healthcare. If the UK can position itself at the forefront of rapidly translating these breakthroughs, it can combat conditions where therapeutic options have previously been very limited and elevate the health of the nation.

2) Regulatory Developments Enabling Faster Access

Earlier access

The UK regulatory environment is also evolving in ways that are enabling faster access to the most promising new therapies. Accelerated and adaptive approval pathways like the Early Access to Medicines Scheme give patients quicker access to innovative medicines for life-threatening or seriously debilitating conditions, even before full regulatory approval is obtained, creating an opportunity to generate real-world evidence (RWE) that might support global patient access objectives.

Mutual recognition

The UK’s regulatory flexibility through mutual recognition (bi-directional acceptance) of international decisions between the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and also the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Furthermore, the UK, Australia, Canada, Singapore and Switzerland participate in an “Access Consortium”, where members cooperate to align regulation requirements for new substances, generics, biosimilars and complementary health products. Project Orbis enables simultaneous applications to participating regulatory agencies for oncology therapeutics. This prevents duplication of effort and enables simultaneous drug reviews. The MHRA now aims to create the “quickest, simplest regulatory approval in the world for companies seeking rapid market access” and a number of companies have utilised these opportunities to achieve approvals before EMA decisions. The Innovation Passport may also offer companies a useful tool to navigate the requirements of key stakeholders throughout drug development.

Real World Evidence

There is increasing acceptance of RWE by regulators and health technology assessment bodies, including the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), actively encouraging companies to supplement submissions with RWE derived from NHS patient data as this can provide additional evidence to support earlier and wider patient access. Given the scientific and the regulatory reforms above, the ability to use RWE is critical to being able to inform earlier access and conditional approval. The recent NICE RWE framework provides clarity on best practices for generating meaningful RWE. The US FDA has similarly published a framework for RWE but NICE’s work leads the way in Europe and is influencing the adoption of standards in Europe for RWE.

3) Evolving Data Environment Creating New Insights

Access to NHS patient data is also rapidly improving thanks to Secure Data Environments (SDEs) that link different healthcare datasets in England. In addition, Data Safe Havens in Scotland and Secure Anonymised Information Linkage data set (SAIL) in Wales and Honest Broker Service in Northern Ireland aim to achieve similar objectives.

At its core, an SDE allows the linking of primary and acute healthcare activity as well as prescribing data at the patient level, along with associated patient characteristics including demographics (age, sex, ethnicity) and social determinants of health. In addition, there is the potential to link in multi-modal data including pathology, imaging, genomics as well as patient reported outcomes and patient generated data. This wealth of longitudinal, patient-level real-world data can generate valuable insights and accelerate research across the product life cycle, from clinical trials (feasibility and enrolment) to market access (including supporting authorisation, cost effectiveness and reimbursement), through to supporting uptake (with case finding and risk stratification) to post-marketing surveillance. Large scale longitudinal data linking detailed patient characteristics, diagnostics, therapies and outcomes at patient level is a critical requirement in the training models for diagnosis and therapy and in the application of new digital tools. The universal coverage of the NHS, the diverse population, and the unique patient identifier enable rich longitudinal data at levels that rival the best in the world.

For pharma, medtech and health tech companies, easier access to granular real-world data on NHS patients provides huge commercial opportunities to support activities like cohort identification, evidence generation, and prospective analyses. The challenge is being able to access this rich data in a timely way for legitimate use cases with appropriate protection for safe data. Historically, the NHS has prioritised access for academics and clinicians but not commercial use cases. The recent change is to align the data strategy with the life sciences strategy and hence actively seek to support the appropriate use of patient data.

4) Collaborative Opportunities to Scale Innovation

Emphasis on collaboration

What we are seeing in the UK is a strong emphasis on collaboration, which is a model that will be needed in other global life sciences markets as continued growth in the cost of medicines is put under even greater pressure through major advances in science. This willingness to collaborate is seen in initiatives like the Innovation Passport, offering the first of a kind opportunity globally to collaborate with regulators, HTA, Payors and Providers throughout drug development. The new UK Voluntary scheme is not only a scheme to manage innovation-led growth but also sets the stage for a joint government-industry investment programme to strengthen the UK’s global competitiveness in health and life sciences. Finally, population-based deals with NHS England offer a new model of access where the NHS identifies and treats eligible patients, potentially reducing the need for such large investments in commercialisation resources.

Together, these developments set the stage for much greater collaboration between the NHS and the life sciences industry to co-create value. With the right data environment, the NHS has an opportunity to work hand-in-hand with companies to identify patients for clinical trials, generate evidence, and rapidly scale up cost-effective innovations across the health service with case finding and targeting.

Leading in disease areas

The UK has an opportunity to take a global leadership position by accelerating partnerships in national priority areas that are the biggest killers including cardiovascular disease, obesity, Dementia and Alzheimer’s, cancer, and rare diseases. However, realising this requires coordinated effort across the healthcare system to drive innovation adoption. Some of our observations around these disease areas include:

- A major gap exists in treating high cholesterol patients at risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In a study of 137,000 patients, 70% of CVD events occur in people with high cholesterol (4 mmol/L non-HDL-C) who were not prescribed any cholesterol-lowering medication in the prior 6 months. Additionally, 40% of patients with non-HDL-C of 3.4 mmol/L are still not on cholesterol medication 6 months after a CVD event, despite clear national guidance that they should be on high-intensity treatment. [1] To address this, these high-risk patients first need to get a cholesterol test. Then they must be followed up to start treatment and titrate up to high-intensity lipid lowering medications, as recommended by NHS England and NICE guidelines. However, significant barriers exist in testing these patients, prescribing appropriate medications, and ensuring they are taking optimal doses.

- Only 61.8% of patients that have suspected Dementia have a diagnosis. Of these patients, the vast majority only have a clinical diagnosis from their GP as opposed to any memory assessment or actual diagnostic test (PET/CT or Cerebrospinal Fluid assessment). Even today there is good evidence that AChE inhibitors and behavioural change (including diet, drinking, smoking, exercise, socialisation and sleep) can delay the onset of dementia. New Disease Modifying Therapies combined with new blood biomarker tests could change the course of Alzheimer’s but only if the system scales up to have widespread diagnosis in place.

- Only 25% of patients are diagnosed with cancer at stage I and II, when the odds of survival are even better than having immunotherapy and cutting-edge cell and gene therapy have, despite the proven impact of existing targeted therapy. Pilots of lung cancer screening in Greater Manchester have shown the potential to flip the proportion of cancers detected early so that 80% are diagnosed in stage I and II. The promise of blood-based biomarkers such as Grail’s Galleri trial could hold out the potential to detect cancer before its even noticed.

- Obesity represents a substantial and escalating challenge that profoundly affects both public health and economic stability. Despite the well-established guidance on the importance of diet and exercise, there remains a persistent resistance to such steady advice. Governmental interventions, including the implementation of a sugar tax, have not been pursued with the necessary resolve. However, the advent of new GLP-1 therapies brings with it the potential for a significant shift, holding an indication that could extend to 15 million individuals and offering the possibility of a considerable positive impact. Nonetheless, there exists a breadth of uncertainties regarding how to effectively facilitate access to these treatments.

- Rare diseases whilst singularly rare are collectively common, as they affect approximately 3.5 million people in the UK today. This patient cohort is growing exponentially due to the latest advancements in technology and genome sequencing programmes and yet up to 50% of patients remain undiagnosed and only 5% of rare disease have one or more approved treatments. Most patients spend years bouncing around the system before being diagnosed. The rarest diseases are treated only in a small number of centres (or even a single centre) making diagnosis and treatment all the more challenging. Systematic use of the national NHS data could enable better case finding and also use of digital monitoring and interactions to support patients remotely, enabling increased diagnosis and access to treatment.

Seizing the opportunity

To seize these opportunities, major change is needed. This can be facilitated particularly by the science, the changing regulatory system and the advances in the data environment. In addition, it will need clinical leaders in each therapeutic area and specialty who embrace innovation, providers who encourage partnering with the life sciences industry and commissioners who align service commissioning with the uptake of new commercial products including drugs, devices, diagnostics, and digital applications.

The way this plays out depends on the scale of medicine and the pattern of how it is procured and prescribed. Highly specialised medicines with small patient numbers are centrally commissioned and delivered by a small set of specialists at tertiary centres making a tight focus possible. Larger patient volumes needing secondary care or primary care prescribing require a correspondingly far wider engagement which is inevitably more variable across the UK.

For the UK to achieve its potential in life sciences, it means that enthusiasm for industry needs to emanate beyond Whitehall and resonate within local systems and providers. Those clinicians, providers and systems that embrace the adoption of innovation in life sciences can see the potential of improving patient outcomes and also attracting additional investment and jobs.

From a life sciences industry perspective, creating successful partnerships generally means:

- Engaging clinical leaders who carry the respect of peers as role models, see the value in innovation, and can demonstrate how to integrate it into the patient pathway,

- Assembling the right collaboration of organisations necessary to implement across the system for the relevant set of patients,

- Securing the required access to core data to enable case finding and measurement of impact,

- Operating with the agility and speed needed to achieve intended impact at scale.

The clinicians, providers and systems who can put these things in place will be the preferred partners of the life sciences industry.

Conclusion

The promise of UK life sciences is undoubtedly immense. But we must be aware it is subject to fierce national and global competition. If the UK can harness its world-leading science, forward-thinking regulators, emerging data capabilities and collaborative opportunities, it has an exciting chance to build the most progressive and pro-innovation life sciences ecosystem globally. This can drive better patient outcomes and health equality, while cementing the UK’s position at the forefront of biopharmaceutical and medtech advancement. But we must act swiftly and purposefully to seize this moment. The promise is within reach, but only possible with coordinated effort and commitment from government, the NHS and industry.

About the authors

Ben Richardson is co-founder and Managing Partner at CF, where he leads our work in Life Sciences and Data Innovation.

Nour Mohanna is an Associate at CF and manages our Life Sciences practice.