The first wave of effective Disease Modifying Therapies (DMT) for Alzheimer’s Disease is on the horizon. This promising development is not just a cause for celebration, but also a call for thoughtful deliberation. It challenges us to rethink how we might best utilise these new therapies, anticipating major adjustments in both political and clinical domains. This will be a massive task, but with the right leadership, the profound potential of these therapies can galvanise the entire ecosystem. The NHS has a proven track record adeptly implementing large-scale changes in disease treatment pathways. A prime example is the incorporation of thrombolysis in UK stroke care. Before its introduction, stroke care was mainly conservative, lacking any disease-modifying treatments. The introduction of a new national stroke strategy, supported by clinical stroke networks and a favourable National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) review of the DMT Alteplase, empowered clinicians and services to swiftly adapt to the new therapeutic approach.

However, the scenario with Alzheimer’s is more intricate. Unlike thrombolysis, these treatments do not offer an immediate reversal of symptoms. Alzheimer’s has a subtler onset, necessitating a more innovative and audacious approach. It demands substantial investment now for benefits that might only be evident in perhaps 20 years. Hence, crafting the right strategy is of paramount importance. Success hinges on strong leadership, reliable data, and solid evidence for every aspect. In essence, designing a comprehensive care pathway, where results might not be immediately apparent, requires careful planning. This article, deeply rooted in CF’s extensive research and experience working on the topic, seeks to highlight key challenges and recommendations, fostering a broader conversation on the next steps.

Context and the Current Medical Pathway

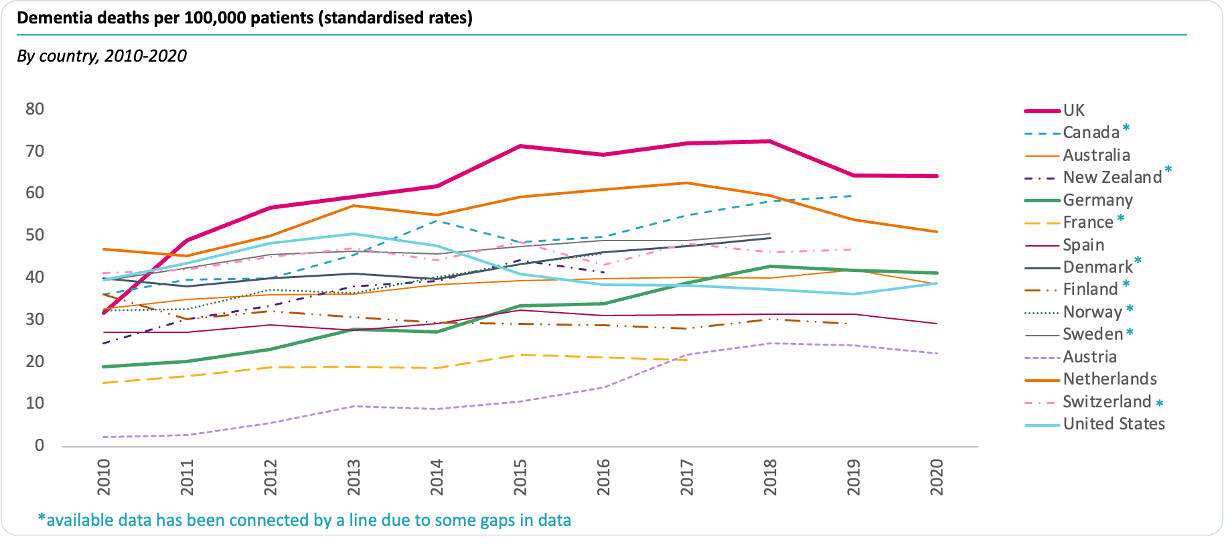

In the UK, many individuals are impacted by dementia in various capacities: whether as a patient, family member, caregiver, or simply as a taxpayer shouldering the rising social care costs. Within the NHS, dementia patients occupy one in every four hospital beds, making it a leading cause of death in the country[1]. Beyond its toll on the health sector, dementia imposes a substantial economic burden, amounting to £35 billion annually[2] for the UK. Alzheimer’s disease stands out as the most prevalent type, representing 50 percent to 70 percent of dementia cases and affecting over 850,000 UK residents[3]. CF, in collaboration with the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR), has conducted an analysis comparing dementia trends across nations. Exhibit 1 shows Dementia mortality rates over time, with the UK lagging behind most comparable nations.

Exhibit 1. Mortality rates for dementia are rising and are higher in the UK than in peers[4].

Historically, dementia has often struggled to move into the spotlight. Up until recently, limited options were available to curb its progression apart from evading some general risk factors and maintaining mental activity. The disease’s impact was primarily managed through diverse care provisions focused on easing the effects on patients and their families. Dementia’s is protracted, terminal, and costly with few tangible solutions.

However, rays of hope have begun to pierce through. For years, medical professionals recognised the presence of amyloid protein plaques in the brain and abnormal tau protein tangles in neurons as Alzheimer’s Disease markers. Yet, the debate remained if these were causative factors or mere outcomes. Now, researchers are advancing monoclonal antibodies targeting these amyloid proteins to eliminate the plaques. A phalanx of drug companies has been racing to bring these molecules to market as the first ‘disease-modifying therapy’. Today, there are over one hundred such drugs in the trial pipeline. While a few have failed at the last hurdle in recent months, with stage III trials giving equivocal results or creating dangerous side effects, three have brought results that offer new hope that Alzheimer’s could be treatable. Donanemab, a medicine from Eli Lilly and Lecanemab from Eisai, have both received FDA approval in the US. Eli Lilly has a second-generation medicine in development, Remternetug, which shows even greater potential. However, ahead of planting a flag of victory, various challenges lie ahead:

- The available treatments have limitations; they decelerate the decline rather than completely stopping progression or improving symptoms.

- Because of this, they need to be administered in the very early stages of the disease for maximum impact , which creates several practical considerations to overcome, including how to find and screen these people into treatment

- The longer-term safety profile and clinical impact of treating ‘healthy’ people over several decades is not fully known. However, some studies have found amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) on MRI following treatment linked to oedema/effusion (ARIA-E) and haemosiderosis/microhaemorrhages (ARIA-H). These can present clinically as accelerated symptoms of Alzheimer’s[5]

- In crude economic terms, paying for an expensive new NHS pathway now to impact the government’s social care bill in a decade or two is a complex political decision

- Practically, there will be an inherent challenge to achieve cost-effectiveness that meets Health Technology Appraisal (HTA) requirements for a product that achieves downstream benefits in terms of slowed decline with potentially limited cost reduction

- Implementing such a revolutionary therapy into the health system requires significant remodelling of current pathways.

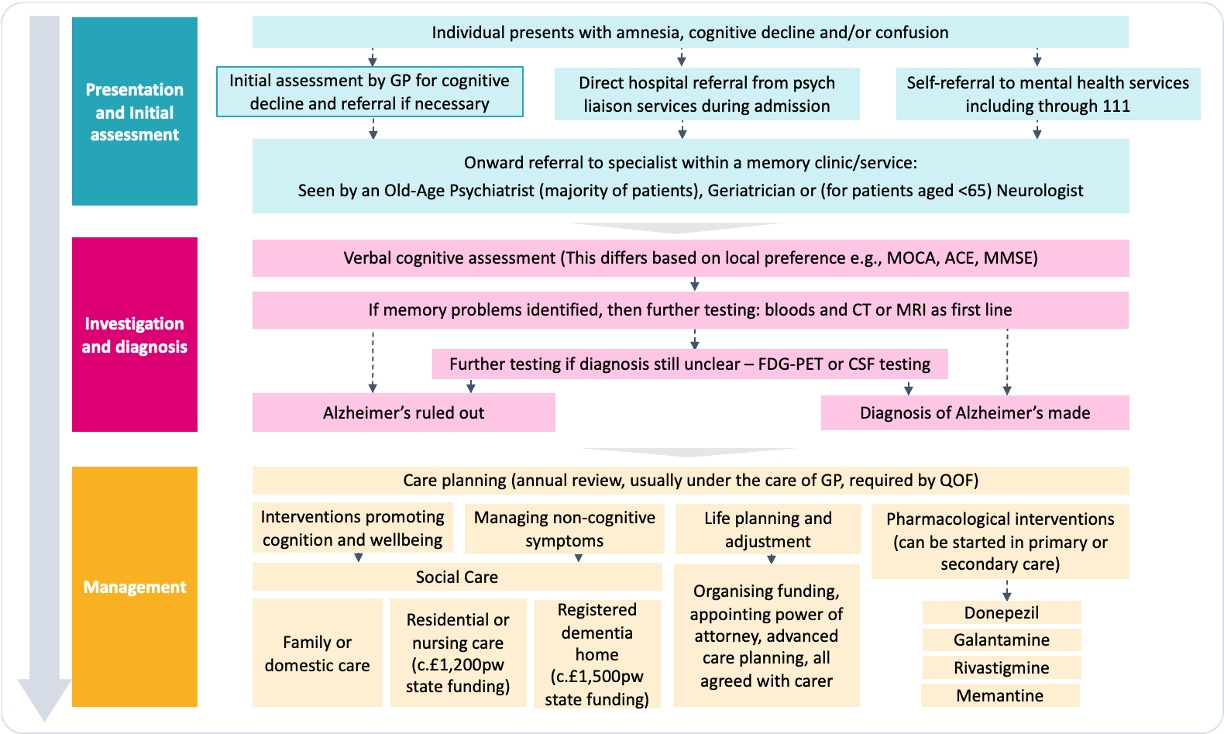

Exhibit 2: Diagram of the current Alzheimer’s clinical pathway[6].

What do we need to do to prepare for DMTs?

While developing these medicines is an enormous achievement, preparing the political and clinical landscape to use them effectively is almost as challenging. Over the last year, CF has been engaged with dozens of leaders in the field to understand the current state of the Alzheimer’s ecosystem. Our aim was to pinpoint and articulate the primary challenges in making this treatment pathway a clinical reality. Today’s clinical model will not work in the future. DMTs will need large-scale clinical pathway change to be effective at scale. Presently, and perhaps understandably, the approaches to Alzheimer’s care vary and lack standardisation across the UK. In theory, after presenting to a GP with cognitive decline, an individual may be referred to a specialist memory clinic and seen by several specialities, including old age psychiatry, neurology or geriatrics. The individual might then undergo investigation through verbal cognitive assessments, CT or MRI and potentially PET scanning or CSF testing for a conclusive Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Upon confirmation, the individual may be offered lifestyle interventions to promote cognition and manage the effects alongside some relatively ineffective drugs to manage symptoms (Exhibit 2). However, in practice, a small minority follow this path. Most sufferers are never formally diagnosed, and dementia is diagnosed clinically, typically at an advanced stage in the disease. As Alzheimer’s advances, the bulk of the everyday care responsibility shifts to social care, as depicted in Exhibit 2. Meanwhile, DMTs must be prescribed early – ideally pre-symptomatically – after specialist diagnosis and monitored for the rest of the person’s life. We have identified five areas to consider when planning to integrate DMTs into the current system.

1. Design and adopt a cohesive clinical pathway and delivery model

Develop diagnostic and monitoring capacity and capabilities. Historically, due to limited treatment alternatives that could alter the disease’s progression, there hasn’t been a push to enhance the precision or timeliness of Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Conclusive diagnosis is possible through expensive PET scanning and skilled, invasive spinal fluid analysis. It seems far-fetched that these diagnostic methods will be implemented widely in population screenings to detect early, pre-symptomatic cases. This would only be viable with significant ongoing investment in capacity, infrastructure and upskilling a larger workforce. The introduction of sensitive blood biomarkers might mitigate some of these challenges. Tests that evaluate markers like Amyloid Beta ratios and p-Tau levels have, in some instances, indicated a higher precision in predicting Alzheimer’s onset compared to PET scans. These could serve as preliminary indicators of asymptomatic conditions, which could then be validated through CSF sampling in patients who test positive[7]. These tests are currently in their initial testing stages, but the sustainability of the pathway hinges on three potential uses of blood biomarkers:

- In the near term, as pre-screening tools to exclude individuals who are likely to be amyloid negative on CSF or PET

- In the medium term, as a standalone diagnostic tool without the need for confirmatory CSF or PET testing

- Once DMTs become more widely used, to monitor the disease-modifying effects of the medicines.

Define pathway ‘ownership’. A shared view of which speciality is best placed to ‘own the pathway’, coordinate a standard approach and deliver DMTs within the secondary care ecosystem is essential. As it stands, psychiatry carries out most of the assessment and initiation of treatment in the UK, and 81 percent of psychiatrists agree that Old Age Psychiatry should be the specialty to provide disease-modifying treatments[8]. However, for these medicines to be maximally effective, they need to be given in the earliest stages of the condition and likely before a person reaches ‘old age’. Although psychiatry has the most contact with patients being assessed and treated for Alzheimer’s, less than 10 percent of psychiatrists have sufficient access to or experience with advanced diagnostics like molecular biomarker tests, and only 36 percent of psychiatrists think that their services could adapt rapidly to DMTs. On the other hand, neurologists provide a more specialist service with greater access to advanced diagnostics. However, they have fewer patients today, and scaling up the care provided within the speciality could present challenges.

2. Plan for the financial implications

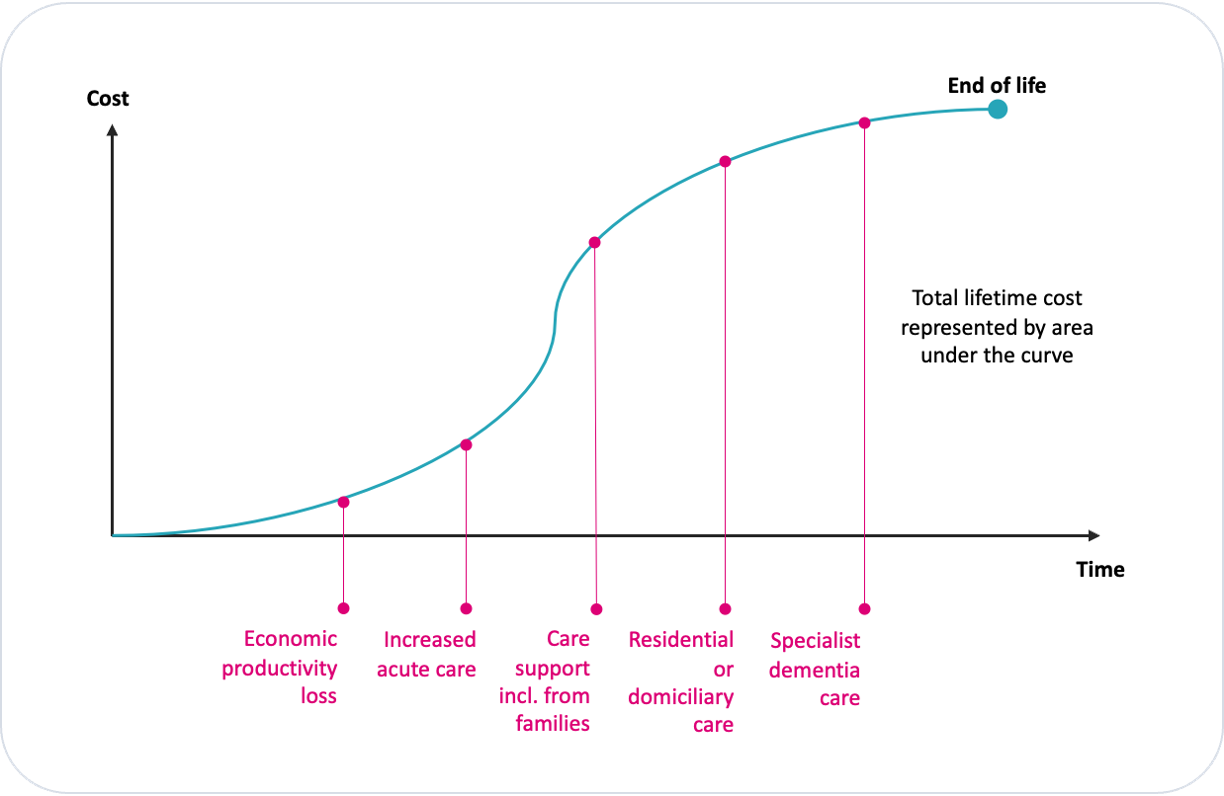

Determine an accurate average cost profile for Alzheimer’s patients. It stands to reason that the costs of dementia follow a curve that ascends to a peak as the disease progresses, as depicted in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3. Illustrative time/cost curve to show the cost of Alzheimer’s care over time.

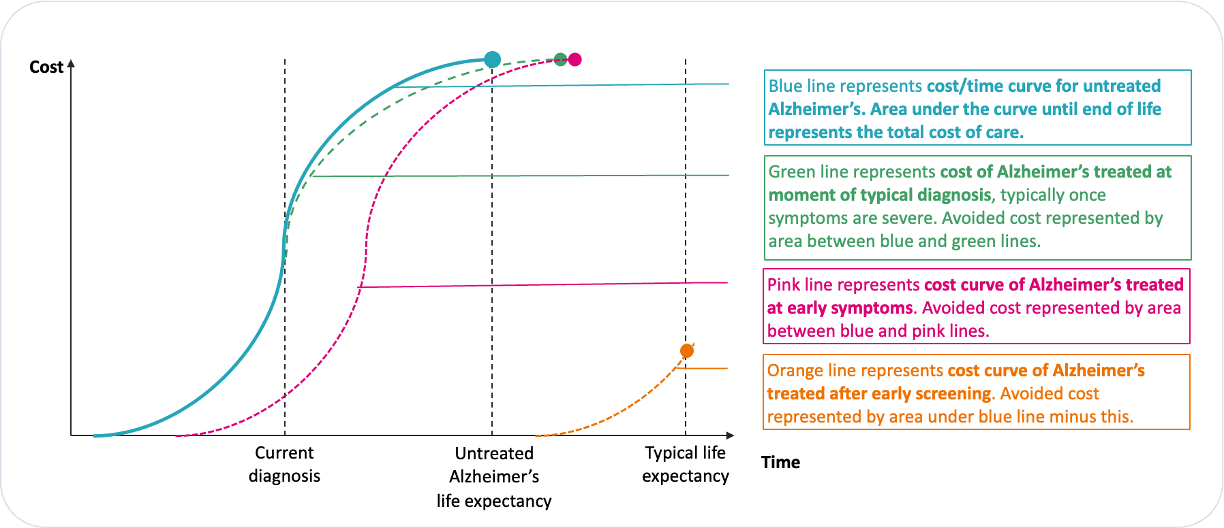

Model the health economics of the new pathway. Emerging therapies are projected to adjust this cost trajectory to the right, potentially by margins observed in clinical trials, that is by 20 percent to 27 percent. As this happens, the associated costs of disease progression are also delayed and may be avoided in part or altogether as progression is delayed beyond a natural lifespan. Consequently, the aggregate cost of dementia for an individual, symbolised by the area under the curve, is reduced even before factoring in the cost of the new treatment pathways (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4. Illustrative curves to show how new therapies might shift the cost of Alzheimer’s care.

Several variables will determine the magnitude of this shift, the cost to facilitate it, and the net financial benefit:

- Population Dynamics: The total number of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s who are eligible for treatment.

- Treatment protocols: Agreed treatment pathways that define the shift scenarios. Considerations include the point in disease progression where screening is feasible and the role of biomarkers.

- Pathway efficiency: including the efficacy of case finding, the occurrence of false negatives during screening and patient adherence to treatment.

- Therapeutic impact: A comprehensive grasp of how treatments influence the cost over time. For instance, while Donanemab decelerated the deterioration of memory and cognitive functions by over 20 percent, it also led to a 40 percent reduction in the decline of daily activities. such as driving, doing hobbies and managing finances. This, in turn, reshapes and repositions the cost curve.

- Life expectancy: Assessment of whether therapies extend life expectancy and, therefore, to what extent costs are just deferred rather than avoided.

- Technological costs: Cost of the new technologies, including and BBMs (Blood-Based Markers).

- Operational costs: Expenses related to the entire care pathway, from identifying potential cases to investing in training, diagnostics, monitoring, and enhancing clinical capabilities.

Although almost certain to reduce costs in the long term, the approved use of potential future DMTs would initially increase the national cost of health and care provision. During the HTA process in the UK, costs and benefits that occur in the future are considered and discounted according to NICE CEA methodology[9]. The constraints this imposes may create an uphill struggle to demonstrate cost-effectiveness in the early years of deployment while care costs are double running with treatment and before a generic alternative is available. The government may need to intervene and create a practical workaround, for example, as happened with the Cancer Drugs Fund to support high-cost cancer drugs that did not meet NICE policy. Policymakers must be equipped with evidence to make decisions that benefit the economy and healthcare system.

3. Navigate NHS complexity and contracting at scale to pilot the new pathway

Adopt a practical approach to navigating NHS complexity. It is crucial to grasp the intricate nature of the NHS, and understand that, just because a medicine or clinical pathway is approved by NICE and made available, it does not guarantee its immediate universal deployment to patients. Establishing an approach to governance and accountability with NHS partners is required to enable the pathway to achieve broader success, as well as conducting practical discussions and planning with commissioners, clinicians and medicines optimisation committees.

Pilot care pathways systematically through Integrated Care Systems (ICSs): The success of a new Alzheimer’s care pathway hinges on the effective engagement of ICSs. This ensures the pathway is tailored to meet local requirements. The pathway would need to be co-designed with leading clinicians in selected local systems to create exemplar pathways that Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) can commission and drive in a steady state. The proof of concept must be piloted in carefully selected ICSs with the bandwidth and desire to focus on innovative care delivery. For effective change to happen, care could be shared between psychiatry (mental health trusts), acute care, including neurology, and primary care, with ICBs influencing inter-trust collaboration. Once the model has been successfully demonstrated in a series of pioneer systems, these can be rolled out further afield.

Develop a sustainable workforce model: The best route to a sustainable workforce model must be by upskilling existing staff to fill current gaps in expertise, and considering the creation of multi-disciplinary teams with nurse specialists as a new role to bridge any gaps.

Develop referral pathways across regions: To minimize geographical inequalities, regional pathways which allow patients access to treatment at specialised centres across the country should be developed. ICSs provide an opportunity to bring together services and professionals and identify new pathways and models to provide equal treatment and increase diagnosis, reducing the variation across the UK.

4. Develop access to data insights

Focus on collecting routine data effectively: Good routine system data will allow an understanding of the starting point, inform a realistic set of goals, identify areas of opportunity and difficulty and track the impact. Dementia data is often underrepresented due to delayed or partial diagnoses, and more generally, the available mental health data is notably behind acute data. Ensuring this data is collected at the point of care and submitted to national databases should be an NHS-wide focus.

Design the data strategy to collect research evidence: Given the pace of change in Alzheimer’s treatments, the data available for research is critical. Delayed diagnosis has the knock-on effect of low availability of eligible participants for clinical trials. Today, many of those recruited for clinical trials have more advanced stages of the disease, often with mixed pathology; these factors make the impact of an intervention harder to identify – especially if the target of the trial is early pathophysiology or disease progression over time.

Leapfrog current systems and engage patients for data: A key plank in this data strategy will be through self-surveillance. Finding patients means conducting expensive diagnostics in a vast pool of otherwise healthy, relatively young people. Because of this, a different type of approach to managing cognition in populations should be applied, focused on the surveillance of brain health by the population itself. For this to be a viable option, processes for individuals to monitor and manage their own risk of dementia in an ageing population must be provided. This may be done through introducing new processes and technologies such as blood biomarkers and routine cognitive function assessments that assist individuals to self-manage their risk factors better, slow cognitive decline and seek help if their scores cross certain warning thresholds. This should be built in as an integral part of the clinical pathway and driven with a clear public health message.

5. Coordinate the narrative and engage stakeholders effectively

Develop the public health discussion: To engage the target population, a case for change that both understands and addresses front-line resistances must be communicated. Perhaps due to the limited treatment options available and measures to reduce the personal risk of developing Alzheimer’s compared to, for example, diabetes or heart disease, prevention and associated population-based interventions have not been widely prioritised to reduce the prevalence of the condition. Going forward, discussions with healthy people about risk reductions, symptom monitoring and early screening should become routine. Such conversations should become more palatable given the promise of treatments available to delay cognitive deterioration.

Overcome cultural barriers within medicine: Medicine has its own cultural impediments. GPs might postpone diagnoses, believing that definitive labeling could be counterproductive, if not harmful, given the absence of treatments. The scant availability of treatment options underscores the post-diagnosis has amplified the lack of support post-diagnosis and demonstrated the variability of secondary and community care options between geographies. For instance, while NICE recommends annual reviews for diagnosed patients, its implementation is inconsistent even though QOF rewards GPs for this service.

Identifying where the most significant cultural barriers exist and resourcing a compelling counter-narrative will be necessary to a successful pathway. As new medicines emerge, endorsement and guidance from esteemed opinion leaders in primary and secondary care are crucial for enabling clinicians to find, assess and refer their patients. In addition to this, they will need the training, capacity funding and technological support to implement a novel pathway.

Focus on equitable access: The advent of new innovative diagnostic approaches and the introduction of DMTs necessitates a renewed focus on guaranteeing equitable access to ensure that existing inequalities are not exacerbated. Both inequality of access and differences in tertiary-level expertise result in a postcode lottery for dementia diagnosis and treatment. Geographical separation from major centres and the effects of deprivation create clear hurdles to seeking help, with 64 percent of commissioners and 74 percent of memory services citing deprivation as a barrier[10] to access to diagnosis. Cultural hindrances, such as stigma and distrust in health systems, act as blockers to seeking and accessing medical help. They may also result in delayed diagnosis, with 71 percent of memory services reporting diagnosing people from ethnic minority backgrounds later in disease progression[11]. Additionally, language-based cognitive screening tests form the basis of Alzheimer’s assessment; these may not always be culturally appropriate in terms of language, content and cultural references. Therefore, a proactive stance at the national level to address these disparities becomes paramount as local pilots conclude.

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease has a profound impact on healthcare and the economy in the UK, with a significant number of people affected and huge associated societal costs, making it a pressing issue. The imminent arrival of DMTs for Alzheimer’s is enormously encouraging but requires significant changes in the healthcare system to ensure effective implementation of these treatments. The importance of strategic planning and leadership to prepare for their introduction cannot be overstated.

Five key areas must be considered when integrating DMTs into the healthcare system:

- Designing a cohesive clinical pathway: This involves improving the accuracy and speed of diagnosis, defining pathway ownership, and coordinating a standard approach within the healthcare system.

- Planning for the financial implications: Understanding the cost profile of Alzheimer’s patients and modelling the health economics of the new pathway, considering factors like eligibility, treatment efficiency, and the impact of therapies on overall cost.

- Navigating NHS complexity: Acknowledging the complexities of the healthcare system and establishing governance, accountability, and practical discussions with various stakeholders.

- Access to data insights: Emphasising the importance of data in understanding the current situation, setting goals, and tracking progress in Alzheimer’s care, including self-surveillance by individuals to monitor their risk factors.

- Investing in the narrative: Engaging stakeholders through public health discussions, overcoming cultural barriers, and ensuring equitable access to diagnostics and treatments.

References:

[1]Gov UK, 2022: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/monthlymortalityanalysisenglandandwales/june2022#:~:text=In percent20England percent2C percent20dementia percent20and percent20Alzheimer percent27s,100 percent2C000 percent20people percent20(294 percent20deaths).

[2]Alzheimer’s Society, 2019: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/dementia-scale-impact-numbers

[3]Alzheimer’s Society, 2023: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/difference-between-dementia-alzheimers-disease?page= percent2C2#:~:text=is percent20Alzheimer percent27s percent20disease percent3F-,Alzheimer percent27s percent20disease percent20is percent20the percent20most percent20common percent20cause percent20of percent20dementia.,before percent20symptoms percent20start percent20to percent20show.

[4] CF analysis of OECD data in collaboration with IPPR, published in The Times, September 2023

[5] Hampel et al., Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA): radiological, biological and clinical characteristics, Brain, 2023;, awad188, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad188

[6] CF Analysis

[7] J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022; 9(4): 569–579

[8] Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2021 https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ARUK-Are-we-ready-to-deliver-disease-modifying-treatments_25May21.pdf

[9] https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/chapter/assessing-cost-effectiveness

[10] Alzheimer’s Society, 2021: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-09/regional_variations_increasing_access_to_diagnosis.pdf Client Interviews, CF Analysis

[11] Kate Lee, Alzheimer’s Society, ADI Conference 2022