The NHS in England and the care systems within which it operates across the country are about to undergo the biggest change in a decade. The Health and Care Act 2022 received Royal Assent on 28 April that will establish new ways of integrated working from 1 July.

This comes at a time when NHS priorities to equitably improve access, reduce waiting times, support and grow the workforce and harness the potential of data and intelligence have come under the spotlight. It also comes at a time when the understanding of local population need is seen to be best met through agencies and people working together with an integrated approach.

Following an approach to integrated care relying on coalitions of the willing to work together across systems, the UK government has set out plans to put integrated care systems (ICSs) in England on a statutory footing in the 2021 Health and Care Bill. This will formally establish 42 new partnerships between organisations that come together to plan and deliver healthcare services for their local populations.

These changes create an opportunity to address health inequalities and deliver holistic care in the most appropriate setting whilst relieving the unprecedented pressures on the NHS and care providers.

These reforms could mark a turning point in the drive towards a more integrated healthcare system. Still, to do so, there will need to be a profound cultural shift in support of collaborative working across the boundaries of health, care, prevention and self-care.

As we approach the introduction of ICSs, what can we expect? We outline below 1) the expectations of the new organisations, 2) the requirements of transition to them, 3) the opportunity for improved joint working and 4), and the opportunity to change culture.

- Integrated care boards and partnerships

These integrated care systems exist to achieve four core purposes:

- Improve healthcare outcomes for residents in their system

- Tackle inequalities in access, experience and outcomes

- Enhance productivity and value for money

- Support broader social and economic development

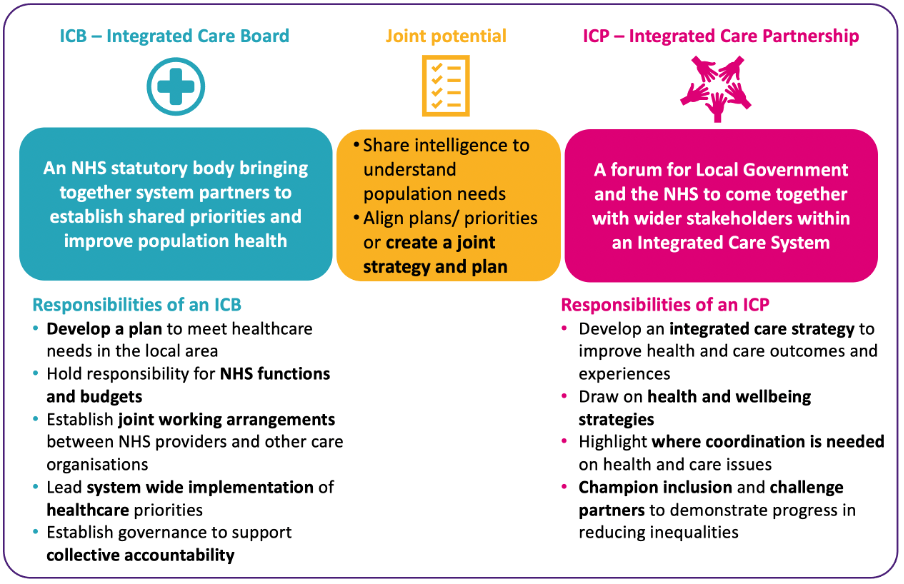

As part of the Act, integrated care systems will evolve to include two new elements alongside existing partnerships and statutory organisational arrangements: integrated care boards (ICBs) and integrated care partnerships (ICPs).

ICBs will be statutory NHS bodies bringing together system partners to establish shared priorities and improve population health. Their responsibilities include:

- Developing a plan to meet healthcare needs in the local area

- Holding responsibility for NHS functions and budgets

- Establishing joint working arrangements between NHS providers and other care organisations

- Leading system-wide implementation of healthcare priorities

- Establishing governance to support collective accountability

ICPs are a forum for local government and the NHS to collaborate with wider stakeholders within an integrated care system. They are responsible for:

- Developing an integrated care strategy to improve healthcare outcomes and experiences

- Drawing on health and wellbeing strategies

- Highlighting where coordination is needed on healthcare issues

- Championing inclusion and challenging partners to demonstrate progress in reducing inequalities

In practice, the current bill allows for ICBs and ICPs to work together to create a shared plan for their population. Membership arrangements for both are generally permissive, with a limited number of prescribed roles for the ICB and the potential for a large number of members on the ICP, acknowledging that the ICP will still need to be operationally effective to discharge its duties.

The question across the country now is: how quickly can ICBs and ICPs establish themselves whilst also ensuring that focus at place level is not ignored?

- The transition to ICSs

A notable absence in ICSs will be clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), all of which will be abolished with the establishment of ICBs. The role of each ICB will not simply be a rebranded CCG, though; for example, provider collaboratives may take on greater commissioning roles in their local systems in future.

All 42 ICSs in England were expected to be fully operational by April 2022; however, the establishment of ICBs and the abolition of CCGs will now be delayed until at least July 2022 to allow for the bill’s progress through the remaining parliamentary stages.

Although the decision to delay the launch of ICBs will prolong uncertainty, the new target does provide some additional flexibility for systems preparing for the new statutory arrangements. This provides more time for ICBs to begin to come together and develop in shadow form whilst CCGs continue to carry out their functions. It also creates more breathing space to develop operating models for ICSs at all levels — from neighbourhoods/primary care networks (PCNs) through to places, collaboratives and systems as a whole.

We are now in a period where places, systems and national efforts to unlock the potential of ICSs could be the difference between success and failure. For example, identification of data required to inform decision-making at the local level could be supported by nationally available data across the NHS and social care.

Equally, a concerted effort to support systems to identify local population needs will enable them to create strategic objectives and prioritised, targeted plans to hit the ground running and make a positive impact as soon as possible.

The greater the level of support provided nationally and locally for ICSs to get off to a strong start, the greater the chances are of care access, experience and outcomes improving at local levels within those systems.

- Improving joint working

There is enormous joint potential at the intersection between ICBs and ICPs to share intelligence to understand population needs and align priorities as part of a joint integrated care strategy.

One of the biggest strengths of ICSs so far has been improving joint working between partner organisations; 90 per cent of system leaders believe they have been able to improve joint working quite or very effectively. The Covid pandemic, in particular, showcased the potential for joint working not seen during the era of sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) and early ICSs.

Collaborating as ICSs will help healthcare organisations tackle complex challenges, including acting sooner to help those with preventable conditions, supporting those with long-term conditions or mental health issues and getting the best from collective resources so that people get care as quickly as possible.

However, analysis by CF and the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) indicates there are still unequal levels of integration across the country, with significant variation in integration maturity between ICSs. For instance, the maternal mortality rate is 16 times higher in the Sussex and East Surrey ICS than in the Suffolk and North East Essex ICS.

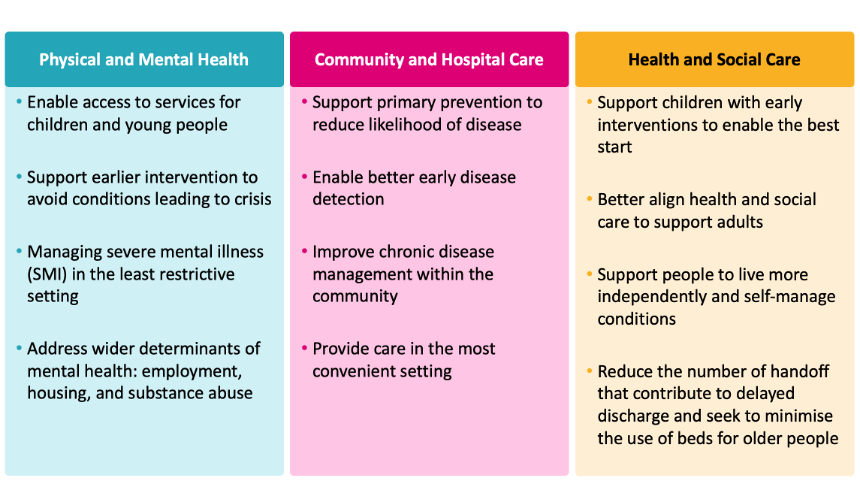

We have identified three chasms that exist within healthcare systems, which ICSs would be ideally placed to bridge with the right support and willingness. These cover physical and mental health, community and hospital care and health and social care. Together with the IPPR, CF has created an integration index that seeks to address integration and allow ICSs to understand where they are and consider their own priorities.

If all ICSs matched the outcomes seen in the top 25 per cent of the most integrated ICSs, it could mean:

- 42,600 bed days saved in hospital due to fewer delayed discharges

- 63,300 additional people with complicated mental health problems receiving a care plan

- 68,600 potential fewer A&E attendances by people with mental health problems

The pandemic, in particular, has shone a light on stark inequalities for local populations across the country in terms of access, experience and outcomes. Improving integration and joint working with partners at all levels will support progress in reducing inequalities and improving outcomes across the country.

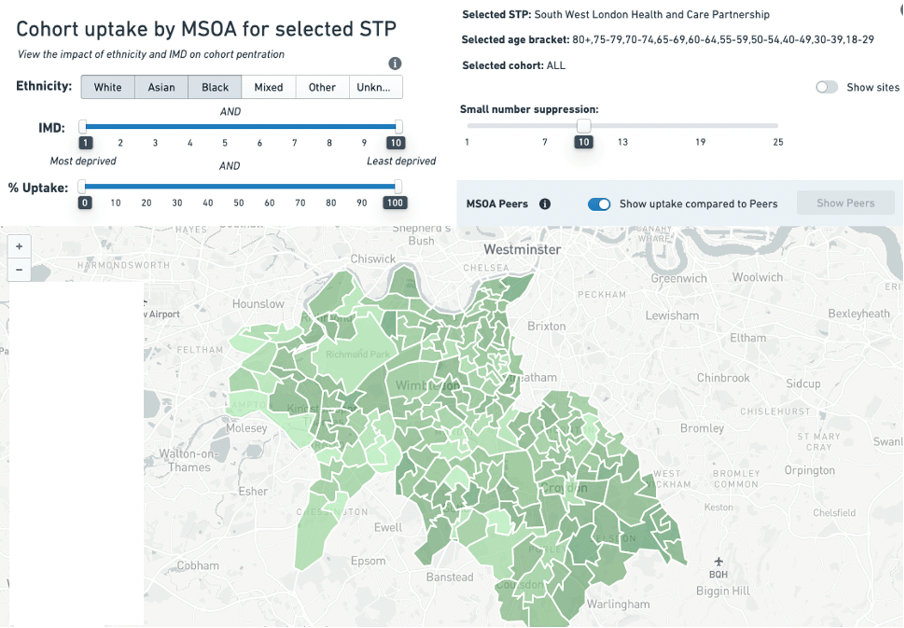

The ‘Core20plus5’ approach to identifying population groups who are most deprived and have the greatest healthcare needs is an example where an integrated approach could make significant difference. Covid vaccine uptake is another example where specific population groups require different approaches and the use of data to understand this uptake in local areas by ethnicity is now being realised. This includes the CF Vaccine Equalities Tool as shown below.

Focus in this area now will likely be on:

- Can ICSs discard organisational boundaries as far as possible to bridge the chasms that negatively impact on local people’s care experience and outcomes?

- Will there be a sustained focus on harnessing national and local data to have a meaningful impact on healthcare inequalities?

- Will the shift to more integrated working unlock better value for money in a national health system that is under intense financial pressure?

- Creating a shared vision, mission and priorities

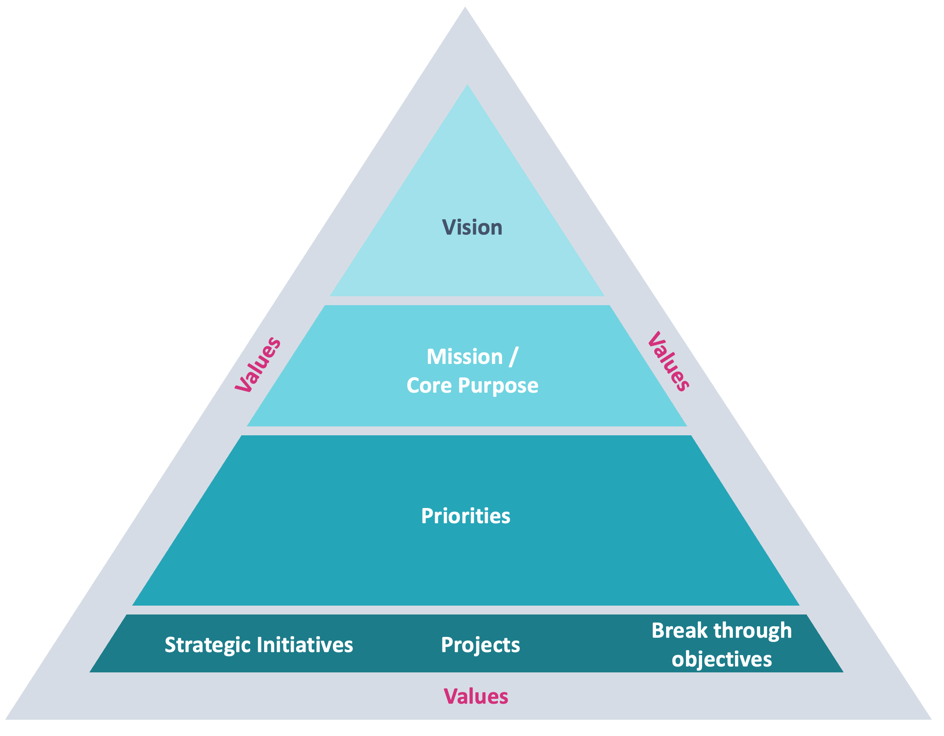

ICSs will need a clear vision to meet the needs of their population. To meet this vision over time, a relentless focus on prioritisation of effort is likely needed to develop trusted relationships across healthcare organisations. Avoiding the pitfall of ‘everything is a priority now’ by focusing on strategic objectives over time will be critical.

As observed by Chris Ham in his snapshot summary, the conditions for successful integrated care will rely on trust and respect being restored with less reliance on regulatory oversight and greater focus on collective accountability at system and local levels. Top-level objective setting from the centre will need to reduce to enable ICSs to thrive and meet local population needs.

Adopting approaches such as ‘True North’ to create and confirm an ICS vision that relates to shared values across all system partners can help create focused priorities and objectives for the coming years. Involvement of multiple system stakeholders — including local delivery partners, citizens and regulators — will all help to create the core purpose that everyone can commit to.

The role of primary care will be important at all levels of an ICS from neighbourhood and PCN level through to place-based commissioning and delivery (and as part of system strategies set by ICPs). In a future where the primary care membership model of CCGs will be abolished, the need to engage primary care actively in leadership, commissioning and delivery decision-making should be paid attention to.

The goal now will be for systems to take the time prior to July to work together on their shared purpose — involving neighbourhoods, places and organisations to shape it. The road ahead is full of opportunity at a time of great challenge, and it is time for ICSs to be supported and permitted to bring people together for the good of their populations.

Phil Livingstone